HERITAGE SITES II

Himalayan Dragons

http://www.essenes.net/pdf/ACollectionOfStudiesOnBon.pdf

http://www.essenes.net/pdf/ACollectionOfStudiesOnBon.pdf

Bon of Tibet

The minority Bon-Po faith of Tibet represents a continuing stream of religious knowledge and practise dating back in time to before prehistory. Bon-Po has sought throughout its existence to include best practise from other faiths into which it has come into contact. It has absorbed ideas wherever it can. Consequently today it is a mixture of Buddhism, Shamanism and magic rituals. It is the old faith of Tibet.

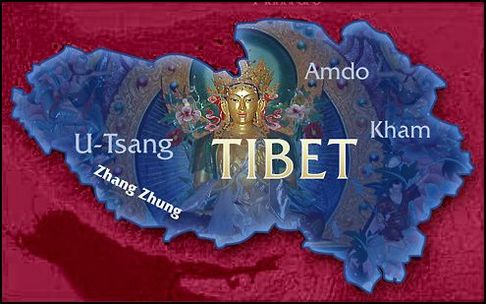

There is much written about this indigenous pre-Buddhist culture and religion of Tibet that is speculative. It is challenging to create a narrative that presents a well-rounded perspective of these ancient peoples, due to several facts, some of these being that the roots of Bon existed as an oral tradition, that the ancient Bon later developed the spoken and written language of Zhang Zhung that was thought to be extinct or even mythical, and that the complex influences between Bon and Buddhist cultures have blurred the lines of distinction between these two.

The Bon culture as narrated by the Bon, speak of its roots spanning 18,000 years, and there is growing archeological evidence to substantiate this. Many references exist in the vast reservoir of Tibetan scriptures but not until the American John Vincent Bellezza began to do extensive research beginning in the early 1990’s did overwhelming evidence of this territory the size of Texas and California combined begin to take shape. In his book, Tibetan Stones of Time:Exploration of the Ancient Bon Kingdom of Zhang Zhung, Bellezza’s findings date the stone remains to the Iron Age, a time span from the First millennium BC to the period of the first Buddhist Kings of the 7th century AD.

Most recently, the German scholar Bruno Baumann has also traveled to this region to experience first hand evidence of these people within the rock art. An excerpt from the recent article by Juergen Kremb Buamann’s new book, The Silver Palace of Garuda, The Discovery of Tibet’s Last Secret, reads as follows.“…the remnants of ancient foundations are everywhere, and the remains of ramparts extending several hundred meters line the top of the cliff. Locals call the mountain “Khardong,” or “In the View of the Palace.” Baumann is quoted as saying, “this must have been where it all began, the cradle of Tibetan culture, in a bleak, high valley settled by nomads, at least 1,000 kilometers (622 miles) from Lhasa.

The cradle of Tibetan culture doesn’t lie in Lhasa,” says Baumann, as he descends from Mt. Kailash, “but in the distant past of the Zhang Zhung kings.” Bon has survived continuously as a living tradition especially among the lay people who despite the over whelming odds, have passed on their culture and religious traditions from generation to generation. As a tribal people profoundly dependent upon their environment, such interconnected awareness permeated every aspect of life. This profound relationship with nature and the five elements of earth, air, fire, water, and empty space is found amongst the worlds’ indigenous people. When disturbances occur and afflictions manifest within these complex relationships, a shaman or Bon priest responds by way of ritual to facilitate the healing of physical and environmental as well as spiritual distress by mediating between the unseen forces to restore harmony.

Scholars have also agreed that Tibetan prayer flags originate from the ancient Bon culture. Symbolizing the union and balance of the five elements, prayer flags are a principle way of transmitting prayer, and acknowledging the divine.

Bon History

Much of Bon history can be viewed as paradoxical, due in part to the nature of the narrative being slowly reshaped by the influence of Buddhism appearing in Tibet in the 7th century. History retold by a Bonpo, as a follower of Bon is called, will speak of lands, by names that have long been forgotten by the modern world. This veiled mystery is a source of fascination to scholars and student alike presenting the earnest seeker a rich opportunity for future discovery. For example, the Bon as a religion is believed to have originated from the land of Olmo Lungring in Tazik. Many modern day scholars recognize Tazik as the present day Tajikistan, which is situated northwest of the once thought to be mythical Kingdom of Zhang –Zhang, which is West of Tibet, near Mt Kailish, a holy place for many religions. As the teachings flourished throughout the ancient empire of Zhang –Zhung they were brought to Central Tibet sometime before 600 A.D. Tibetan Buddhism, distinct from its Indian and other Asian counterparts, arguably owes much of this uniqueness to the influence of Tibetan Bon. Many native Bon elements are obvious within Tibetan Buddhist rituals, and in turn, the New Bon of today reflects Buddhist influence as well. There remain many distinctions within these two religions, but both share a common and ultimate commitment to the enlightenment of all sentient beings. Integral to the religious practice of Bön is a heightened sense of esthetics. Whether it be through the arts, philosophy, theology, mudras, mantras, ritual, dance or astrology, examining, perceiving and experiencing our intrinsic relationship to nature, and to the natural mind is an ever- evolving unfoldment of revelation and practice whose transforming mere existence into an experience of living with universal wisdom and compassion for all.

Bon Spirituality Within present day Bon, are three classifications including Old Bon, Yungdrung Bon, and New Bon. Yungdrung doctrine, or otherwise known as Eternal Bon, is dedicated to perpetuating the teachings of their founder Tonpa Shenrab Miwoche, who occupies a preeminent position in Bon culture similar to that of Sakyamuni in Buddhism. The teachings and practice of Yungdrung Bon contain the Nine Ways or the Nine Gradual Views of Bon, the Four Portals and Treasure as the Fifth, and the External, Internal and Secret Bon.

Bön, was officially recognized in 1978 by the Dalai Lama as the fifth wisdom school of Tibet.

There is much written about this indigenous pre-Buddhist culture and religion of Tibet that is speculative. It is challenging to create a narrative that presents a well-rounded perspective of these ancient peoples, due to several facts, some of these being that the roots of Bon existed as an oral tradition, that the ancient Bon later developed the spoken and written language of Zhang Zhung that was thought to be extinct or even mythical, and that the complex influences between Bon and Buddhist cultures have blurred the lines of distinction between these two.

The Bon culture as narrated by the Bon, speak of its roots spanning 18,000 years, and there is growing archeological evidence to substantiate this. Many references exist in the vast reservoir of Tibetan scriptures but not until the American John Vincent Bellezza began to do extensive research beginning in the early 1990’s did overwhelming evidence of this territory the size of Texas and California combined begin to take shape. In his book, Tibetan Stones of Time:Exploration of the Ancient Bon Kingdom of Zhang Zhung, Bellezza’s findings date the stone remains to the Iron Age, a time span from the First millennium BC to the period of the first Buddhist Kings of the 7th century AD.

Most recently, the German scholar Bruno Baumann has also traveled to this region to experience first hand evidence of these people within the rock art. An excerpt from the recent article by Juergen Kremb Buamann’s new book, The Silver Palace of Garuda, The Discovery of Tibet’s Last Secret, reads as follows.“…the remnants of ancient foundations are everywhere, and the remains of ramparts extending several hundred meters line the top of the cliff. Locals call the mountain “Khardong,” or “In the View of the Palace.” Baumann is quoted as saying, “this must have been where it all began, the cradle of Tibetan culture, in a bleak, high valley settled by nomads, at least 1,000 kilometers (622 miles) from Lhasa.

The cradle of Tibetan culture doesn’t lie in Lhasa,” says Baumann, as he descends from Mt. Kailash, “but in the distant past of the Zhang Zhung kings.” Bon has survived continuously as a living tradition especially among the lay people who despite the over whelming odds, have passed on their culture and religious traditions from generation to generation. As a tribal people profoundly dependent upon their environment, such interconnected awareness permeated every aspect of life. This profound relationship with nature and the five elements of earth, air, fire, water, and empty space is found amongst the worlds’ indigenous people. When disturbances occur and afflictions manifest within these complex relationships, a shaman or Bon priest responds by way of ritual to facilitate the healing of physical and environmental as well as spiritual distress by mediating between the unseen forces to restore harmony.

Scholars have also agreed that Tibetan prayer flags originate from the ancient Bon culture. Symbolizing the union and balance of the five elements, prayer flags are a principle way of transmitting prayer, and acknowledging the divine.

Bon History

Much of Bon history can be viewed as paradoxical, due in part to the nature of the narrative being slowly reshaped by the influence of Buddhism appearing in Tibet in the 7th century. History retold by a Bonpo, as a follower of Bon is called, will speak of lands, by names that have long been forgotten by the modern world. This veiled mystery is a source of fascination to scholars and student alike presenting the earnest seeker a rich opportunity for future discovery. For example, the Bon as a religion is believed to have originated from the land of Olmo Lungring in Tazik. Many modern day scholars recognize Tazik as the present day Tajikistan, which is situated northwest of the once thought to be mythical Kingdom of Zhang –Zhang, which is West of Tibet, near Mt Kailish, a holy place for many religions. As the teachings flourished throughout the ancient empire of Zhang –Zhung they were brought to Central Tibet sometime before 600 A.D. Tibetan Buddhism, distinct from its Indian and other Asian counterparts, arguably owes much of this uniqueness to the influence of Tibetan Bon. Many native Bon elements are obvious within Tibetan Buddhist rituals, and in turn, the New Bon of today reflects Buddhist influence as well. There remain many distinctions within these two religions, but both share a common and ultimate commitment to the enlightenment of all sentient beings. Integral to the religious practice of Bön is a heightened sense of esthetics. Whether it be through the arts, philosophy, theology, mudras, mantras, ritual, dance or astrology, examining, perceiving and experiencing our intrinsic relationship to nature, and to the natural mind is an ever- evolving unfoldment of revelation and practice whose transforming mere existence into an experience of living with universal wisdom and compassion for all.

Bon Spirituality Within present day Bon, are three classifications including Old Bon, Yungdrung Bon, and New Bon. Yungdrung doctrine, or otherwise known as Eternal Bon, is dedicated to perpetuating the teachings of their founder Tonpa Shenrab Miwoche, who occupies a preeminent position in Bon culture similar to that of Sakyamuni in Buddhism. The teachings and practice of Yungdrung Bon contain the Nine Ways or the Nine Gradual Views of Bon, the Four Portals and Treasure as the Fifth, and the External, Internal and Secret Bon.

Bön, was officially recognized in 1978 by the Dalai Lama as the fifth wisdom school of Tibet.

- Cha Shen Thegpa: the Way of Prediction - Describes the four methods of prediction; astrology, ritual examination of causes, and prophecy

- Nang Shen Thegpa: the Way of the Visual World - explains the psychophysical universe, as relating to the origin and nature of gods and demons living in the world and the methodology of exorcism and the liberation of beings through energetic exchange

- Trul Shen Thegpa: the Way of Illusion- rites for dispersing adverse powers

- Si Shen Thegpa: the Way of Existence –describes the phases after death and the methods for guiding living beings toward final liberation

- Ge Nyen Thepga: the Way of a virtuous layperson’s path, offers ten principles of practices for well being, and the practice of fasting

- Drang Song Thegpa: the Way of Monkhood - explains the rules of monastic conduct and the first level of tantric practices

- A Kar Thegpa: the Way of Pure A or Primordial Sound – elucidates higher tantric practices and the necessary rituals of visualization as well as the tantric practice of che rim, explaining how to cut the bonds of rebirth, death and the intermediate state

- Ye Shen Thegpa: the Way of Primordiality – expounds upon the essential reasons for having the appropriate master, place and occasion for tantric practice and emphasizes the perfection tantric process dzog rim, and obtaining the illusory body, gyu lu.

- La na me ba: the Unsurpassable Way – details the doctrine, views, meditation and behavior of the Great Perfection, Dzogchen

Before Buddhism was introduced to Tibet the people there practiced the Bon religion. Tibetan Buddhism absorbed elements of Bon when it developed in the A.D. 8th century. Bon religion is an ancient shamanist religion with esoteric rituals, exorcisms, talismans, spells, incantations, drumming, sacrifices, a pantheon gods and evil spirits, and a cult of the dead. Originating in Tibet, it predates Buddhism there, has greatly influenced Tibetan Buddhism and is still practiced by the Bonpo people. Prayer flags, prayers wheels, sky burials, festival devil dances, spirit traps, rubbing holy stones—things that are associated with Tibetan religion and Tibetan Buddhism—all evolved from the Bon religion. The Tibetan scholar David Snellgrove once said “Every Tibetan is a bonpo at heart.” See Bon Religion

Buddhism developed out of Hinduism. Most Tibetan Buddhist pay homage to gods found in both religions as well as animist and shamanist ones. Some Himalayan people say "the mountain gods are Buddhists." Early Tibetan tribes were warlike. It has been argued that Buddhism pacified them, making it easier for the Chinese and tribes from the north to conquer them.

The story of the introduction of Buddhism to Tibet is a mix of history and legends about religious heros and their conquest of local gods and spirits and converting them to Buddhism. Most of the religious heros are believed to have been real people put some of their achievements and characteristics are clearly legendary and supernatural. Tibetan Buddhist heros are often regarded as manifestations or reincarnations of gods, spirits and bodhisattvas and their “historical” achievements often involve fighting and defeating evil gods and spirits and allying themselves with good gods and bodhisattvas and wrathful and vengeful ones.

Shamanism in the Native Bon Tradition of Tibet

- by Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche

Shamanism, an ancient Tradition found in cultures throughout the world, values a balanced relationship between humanity and Nature. Because of the recent alarming increase in pollution and exploitation of the environment, along with the consequential negative ramifications, such as the emergence of new illnesses, it has become even more important for humankind to recover the principle of harmony central to Shamanism in order to repair the damage done to the Earth, as well as to save people and Nature from negativity and illness.

There is an ancient Tibetan myth on the origin of negativity that recounts the causes of illness:

From the vast voidness wherein nothing exists, there arose light, Nangwa Oden (Appearance with Light), and also darkness. Male darkness, Munpa Zerden (Rays of Darkness) lay with female darkness, Munji Gyatso (Ocean of Darkness), and by their union whe gave birth to a poisonous egg.

This egg was hatched by the force of its own energy and steam issued into the sky, giving rise to the negative energy of space. Thunder, hail and planetary disturbances came into existence. The albumen spilled onto the Earth and polluted it, giving rise to naga-derived illnesses such as physical handicaps, leprosy and skin diseases. The shell gave rise to harmful weapons and infectious diseases, and the disturbances and illnesses of humans and animals came forth from the membrane. From the yolk essence there came forth Chidag Nagpo (Black Life-Stealing Fiend) with bulging wrathful eyes, gnashing teeth, and matted hair with blood rising into the sky like a cloud, holding the black cross (of evil power) in his right hand and the disease-dispensing lasso in his left.

It was the negative powers of this egg that produced birth, old-age, sickness and death - the four sufferings which are as vast as the ocean.

Black Life-Stealing Fiend is the demon of ignorance, and he has a retinue of four demons. The white demon of jealousy, like a tiger-headed man, forces one to undergo the suffering of birth; the yellow demon of attachment, with a chusin (crocodile) head, forces one to undergo the suffering of illness; and the black demon of hatred, who wears a kapal (skull cap), forces one to undergo the suffering of death.

These five demons together manifest the poisons of the five passions (ignorance, jealousy, pride, attachment and hatred), that give rise to the 80,000 negativities which they introduced into the six realms of existence of beings: gods, demigods, humans, animals, hungry ghosts and hell denizens. These almost completely destroyed the essence of beings and of the Earth.

In that moment the great Bon sage Sangwa Dupa (secret essence) manifested as the wrathful yidam deity Tsochog (Foremost Excellence) and vanquished the five demons. Through the vow the demons were forced by Sangwa Dupa to take on that occasion, his teaching still has the power to communicate with these negative forces.

This is the vow Tibetan shamans recall in rites when they communicate with disturbing spirits, particularly the five great demons, to convince them not to create problems and confusion: "Because of your promise to Sangwa Dupa, you must not disturb my sponsor or my people, for which I pay you with this offering."

In fact in the Tibetan tradition, although the shaman may not see the particular spirit, ordinarily invisible, that is causing a specific problem, it is through the power of the shamanic rite that the shaman contacts the spirit, reminding it of its vow not to disturb humanity. This rite must be performed in the proper way by reciting the myth that recounts the origin of the rite and making appropriate offerings.

This myth comes from the ancient Bon religion of Tibet. According to the teachings of Dzogchen, the highest spiritual path in that tradition, illnesses and disturbances are deemed to be the result of the imbalance caused by the dualistic vision that arises when a person does not remain in the 'natural' state of mind.

Though conceptualising, negative and stressful emotions arise that afflict man with nervous disorders and physical diseases. However, just like the Native American shamans, the shamans of Tibet hold a different view. They believe the source of the illness to be the energy imbalance that humans create between themselves and all existence, where they provoke the spirits of Nature. To heal people, the Earth and space, it is necessary to contact these spirits, in order to restore balance and re-establish harmonious relationship with them.

These spirits (that humans disturb by their various activities) are the spirits of the five elements (space, air, fire, water, and earth), of the four seasons, and the natural spirits of the Earth, (trees, rocks, mountains, rivers, plants, the sky, sun and moon, stars and clouds, etc.,).

People disturb the sadag (Earth spirits), the nye (tree spirits), and the tsen (rock spirits), by digging the ground, cutting down trees and excavating mountains. They provoke the theurang (space spirits) by polluting the air, and they disturb the lu (water spirits) by polluting rivers and lakes.

This pollution affects people's inner being as well as the environment. By polluting space, they pollute their minds; by polluting fire, they pollute their body heat; by polluting external water, people internally pollute their blood; by polluting the earth, they pollute their bodies.

Shamans do heal adventitious, mental and physical disturbances, though only at a gross level. According to the Bon teachings, ailments are caused either by nad (physical disease) or by a disturbance of vital energy by a don (spirit). The sick person is diagnosed by a doctor to ascertain if the illness has a physical etiology, through urine and pulse tests.

However, if it is found to be due to a provocation of energy by a spirit, then it will be necessary to call a shaman healer. Through divination or astrology, or sometimes through meditation, the shaman will discover the nature of the disturbing spirit and the way to remove it, such as by payment of a ransom.

The founder of the native Tibetan Bon religious tradtion was Tonpa Shenrab Miwoche, and a follower of his teachings is called a Bonpo. An ancient term for a master practitioner of Shenrab's teachings is Shen. Bonpos classify the spiritual teachings and practices Shenrab expounded, in nine ways or vehicles. These are divided into four causal and five resultant ways.

Tibetan Shamanism is found in the first four causal ways. Shamans in Tibet take a very earthy and dualistic approach to life, healing the disturbances and illnesses in this life without being concerned about the next life.

Although their motivation is the altruistic ambition to relieve others' suffering, it lacks the generation of universal compassion that is found in the resultant ways. It is the absence of the cultivation of compassion for all sentient beings, and the aspiration to realise Buddahood as the inspiration for practice, that is the major difference between the causal and resultant ways.

These first four causal ways of the native Tibetan shamans' paths, are called: Chashen (The way of the Shen of Prediction), Nangshen (The Way of the Shen of the Visible World), Trulshen (The Way of the Shen of 'Magical' Illusion), and Sichen (The way of the Shen of Existence).

Chashen, the first way, comprises medical diagnosis and healing, as well as various ancient divination and astrological rites performed by the shaman to determine whether the person who needs to be healed has an energetic imbalance, or is being provoked by a demonic spirit, or negative energy (as mentioned above). Nowadays these rites are still widely practised in Tibetan communitites.

The second way, Nangshen, comprises various rituals for purification to summon energy and enhance prosperity, to suppress and liberate negative forces, and to invoke and make offerings to powerful deities and pay ransoms to demonic spirits.

These practices are very widespread in Tibet. Families perform small ones, while large scale ones are usually performed collectively in towns, villages and monasteries. In ransom rites, an effigy is prepared which represents the beneficiary of the rite, or the shamanic practitioner who is performing it. I remember when my mother had been ill for a long time we tried to heal her by means of different medical treatments, but nothing helped. We then performed several minor rites, but these did not work either. So finally we invited some shaman monks, who performed a big ransom rite, in which they prepared a large effigy of her (in fact, people often make life-size effigies) and we dressed it in her clothes, so that it was very lifelike and resembled her closely. Then we performed the ritual, offering the effigy in her place to repay her karmic debt to spirits. She was given a new name, Yehe Lhamo, in place of her old name, Drolma, as a kind of new birth into the world, and she recovered from her illness.

Shamans of the third way, Trulshen, go where there is strong, wild energy, where they perform practices to conquer the spirits and demons that inhabit those places, subjugating them into their service. One achieves this through practising mantra (words of magic power), mudra (meaningful hand gestures to communicate with gods and spirits), and samadhi (meditation), while performing sadhanas (devotional practices) to engage various wrathful goddesses such as Walmo and Chenmo. The aim of these wrathful practices, which are directed against enemies of the teaching, are to protect the practitioners and the teaching against danger and threats.

It is very important to perform these actions with an attitude of love and compassion towards other beings, and should not be performed solely for the shaman's benefit.

Working with the soul of the living and the dead, is the most important feature of the fourth way, Sichen, which contains a detailed explanation of the principle of the la (soul), yid (mind), and sem (thinking mind). "The la is the karmic trace, which is stored in the kunzhi namshe, (or base consciousness). The sem follows the karmic trace and produces blissful, painful and neutral experiences which are experienced by the yid."

When a living person's soul is lost, shattered, or disordered, there are practices to recall and reinforce its energy, such as soul retrieval. In relation to the dead, there are explanations of 81 different types of death, such as accidental death, suicide, murder, and sinister death.

Following these kinds of death, it is very important to perform appropriate rites, especially if the death occurs in a place which is energetically disturbed (for instance, a place where untoward events such as accidents regularly occur).

A particular specific method found in this way, is that of the 'four doors', to vanquish negative spirits, using 360 different methods. There are also funeral rites to guide the soul immediately after death, communicating with the ghost of the deceased and feeding it until its next rebirth.

One of the most important practices performed by Tibetan shamans of the sichen path is soul retrieval - Lalu (literally redeeming, or buying back the soul), and Chilu, (redeeming the life-energy).

These practices are widespread in the Bon tradition and also in all Tibetan Buddhist schools. One could discuss the soul and life-energy philosophically at great length; but in brief, life energy is the force that keeps mind and body together and the soul is the vital energy of the person. External negativities can cause these two forces to decline, be disturbed, or even lost. Through the lalu and chilu rites, these forces can be recalled, repaired and balanced. To recall the life force in the chilu ritual, the shaman sends out energy as light rays, like a hook, to catch the blessings of the Buddhas; the power of all the protectors, protectresses and guardians; the magic power of all the spirits and eight classes of beings; and the vital energy of the life force of the beings of the six realms. He summons this powerful energy from all the corners of the universe and condenses it into syllables, which he introduces into the disturbed person's heart through his crown chakra, reinforcing his life force.

Shamans perform several different soul retrieval rites. In one rite, a deer - that will recall the soul - is placed on a plate floating in a vase of milk. The shaman then stirs the milk with a dadar (auspicious long life arrow), in order to determine whether the soul has returned. In fact if the deer is facing the house altar when the plate stops turning, the rite has been successful; if it faces the door it has not, and the rite has to be repeated.

In another rite, the beneficiary has to cast white dice on a white cloth, betting against a person of the opposite sign (according to Tibetan astrology), who casts a black dice on a black cloth. When the beneficiary wins this means the rite has been successful.

One of the principle ways of reinforcing the life force is recitation of the mantra of the life deity. The texts say that through this power, the shaman recalls the life force wherever it has strayed. If it is finished, he prolongs it; if it has declined, he reinforces it; if it is torn, he sews it; if it has been severed, he fastens it.

Lalu soul retrieval is performed in a similar way: the shaman summons the spirit which has stolen, or disturbed the person's soul, and offers it a torma (offering cake) representing the union of the five sense pleasures - completely satisfying it with the visualised object, so it will immediately give back the soul it has taken.

There also seems to be a strong connection between the practice of soul retrieval and the popular lungta practice, which is performed to reinforce fortune and capacity, by 'raising the wind-horse'. This is a very powerful rite, performed by large groups of Tibetans, on top of mountains on the first, or third day of the New Year. The participants arouse and invoke the mountain spirits by making smoke offerings, putting up prayer flags and throwing five-coloured cards bearing mantras into space in order to reinforce prana (vital air), which is the support of the la. In this way the la is also healed and reinforced, and consequently the participants' capacity, fortune and prosperity increase, and whatever venture they undertake becomes successful.

These healing rites, in which Bon masters and shamans communicate (either fully conscious or through out-of-the-body experience) with spirits and demons, are widely practiced in all Tibetan Buddhist schools.

It is interesting to note that one of the ways the Buddhist schools attempted to suppress Bon, was by accusing Bon practitioners of being 'intellectually uncivilized' - of being mere primitive shamans. However, in the deepest sense, shamanic belief is the Tibetans' very lifeblood. Tibetans of any religious school who get ill will enact rituals, such as putting up prayer flags, to invoke their guardian spirits and perform ransom rites to remove disturbing spirits, without a moment's hesitation.

Shamanism contains much wisdom that is used to harmonise imbalances, by working on re-establishing good relationships with spirits. The work of Native American shamans in contacting guardian animals for guidance, strength and knowledge, is of great value for healing and for restoring a harmonious relationship with animals, the elements, the sky and the whole environment.

A practitioner of the Bon ways, however, might warn contemporary western shamans about the dangers inherent in certain of the practices they perform

The drum journey, is one such example, used for finding the 'guardian' animal (which they then trust completely) and collaborate with in healing. It is by no means certain that the 'guardian' animal that the shaman meets during the drum journey will be beneficial. In that kind of journey, or out-of-body experience, one can meet hundreds of different beings, just as a non-human being, coming into the human world, will meet hundreds of humans.

The shamanic experience is very important, so it is crucial to have the right guardian, which must be found through real awareness and realisation.

In Tibet most locations, towns and mountains have their own guardian protectors, just as the various religious schools share protective guardian deities. Yet it was yogis, lamas and realised masters who recognised, subjugated and initiated these powerful beings as dharmapalas, or guardians, of the teachings. Until meeting these masters, many of these beings were wild and untrustworthy spirits or the ghosts of evil or confused people, just as the guardian animals the shaman meets may be evil.

In conclusion, it seems to me that many shamans now active in the West focus on working with the emotions and problems of this life, relating with spirits through shamanic drum journeys to heal themselves and others. This practice is very beneficial in curing mental and physical disturbances, and certainly the work shamans do is also very important to restore ecological balance, but it should not remain at that level.

Rather, their work could be enhanced by deepening their knowledge, to obtain comprehension of the nature of mind, and generating the aspiration to engage in contemplative practice to realise Buddhahood. In similar fashion, if the causal means of shamanism were practiced widely in the world, it would be of great benefit for the environment and the world community.

It would be of even greater benefit if all nine vehicles were practiced.

Lama Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche is the founding director of the Ligmincha Institute, a centre devoted to the education of students in the thought and practice of Bon religious teachings and transmissions. He is also a lineage leader of a living Bonpo tradition having received the precious Bon transmissions directly from his teachers, Lopon Sangye Tenzin and Lopon Tenzin Namdak. In particular, he received the entire oral teachings of Zhang Zhung sNyan rGyad. He is the author of 'Wonders of the Natural Mind; the Essence of Dzogchen in the Native Bon Tradition of Tibet' - a newly-published book ,concerned primarily with communicating the Bonpo view of Dzogchen as a spiritual path. Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche also teaches at Rice University and travels widely in the US and Europe giving workshops.

Buddhism developed out of Hinduism. Most Tibetan Buddhist pay homage to gods found in both religions as well as animist and shamanist ones. Some Himalayan people say "the mountain gods are Buddhists." Early Tibetan tribes were warlike. It has been argued that Buddhism pacified them, making it easier for the Chinese and tribes from the north to conquer them.

The story of the introduction of Buddhism to Tibet is a mix of history and legends about religious heros and their conquest of local gods and spirits and converting them to Buddhism. Most of the religious heros are believed to have been real people put some of their achievements and characteristics are clearly legendary and supernatural. Tibetan Buddhist heros are often regarded as manifestations or reincarnations of gods, spirits and bodhisattvas and their “historical” achievements often involve fighting and defeating evil gods and spirits and allying themselves with good gods and bodhisattvas and wrathful and vengeful ones.

Shamanism in the Native Bon Tradition of Tibet

- by Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche

Shamanism, an ancient Tradition found in cultures throughout the world, values a balanced relationship between humanity and Nature. Because of the recent alarming increase in pollution and exploitation of the environment, along with the consequential negative ramifications, such as the emergence of new illnesses, it has become even more important for humankind to recover the principle of harmony central to Shamanism in order to repair the damage done to the Earth, as well as to save people and Nature from negativity and illness.

There is an ancient Tibetan myth on the origin of negativity that recounts the causes of illness:

From the vast voidness wherein nothing exists, there arose light, Nangwa Oden (Appearance with Light), and also darkness. Male darkness, Munpa Zerden (Rays of Darkness) lay with female darkness, Munji Gyatso (Ocean of Darkness), and by their union whe gave birth to a poisonous egg.

This egg was hatched by the force of its own energy and steam issued into the sky, giving rise to the negative energy of space. Thunder, hail and planetary disturbances came into existence. The albumen spilled onto the Earth and polluted it, giving rise to naga-derived illnesses such as physical handicaps, leprosy and skin diseases. The shell gave rise to harmful weapons and infectious diseases, and the disturbances and illnesses of humans and animals came forth from the membrane. From the yolk essence there came forth Chidag Nagpo (Black Life-Stealing Fiend) with bulging wrathful eyes, gnashing teeth, and matted hair with blood rising into the sky like a cloud, holding the black cross (of evil power) in his right hand and the disease-dispensing lasso in his left.

It was the negative powers of this egg that produced birth, old-age, sickness and death - the four sufferings which are as vast as the ocean.

Black Life-Stealing Fiend is the demon of ignorance, and he has a retinue of four demons. The white demon of jealousy, like a tiger-headed man, forces one to undergo the suffering of birth; the yellow demon of attachment, with a chusin (crocodile) head, forces one to undergo the suffering of illness; and the black demon of hatred, who wears a kapal (skull cap), forces one to undergo the suffering of death.

These five demons together manifest the poisons of the five passions (ignorance, jealousy, pride, attachment and hatred), that give rise to the 80,000 negativities which they introduced into the six realms of existence of beings: gods, demigods, humans, animals, hungry ghosts and hell denizens. These almost completely destroyed the essence of beings and of the Earth.

In that moment the great Bon sage Sangwa Dupa (secret essence) manifested as the wrathful yidam deity Tsochog (Foremost Excellence) and vanquished the five demons. Through the vow the demons were forced by Sangwa Dupa to take on that occasion, his teaching still has the power to communicate with these negative forces.

This is the vow Tibetan shamans recall in rites when they communicate with disturbing spirits, particularly the five great demons, to convince them not to create problems and confusion: "Because of your promise to Sangwa Dupa, you must not disturb my sponsor or my people, for which I pay you with this offering."

In fact in the Tibetan tradition, although the shaman may not see the particular spirit, ordinarily invisible, that is causing a specific problem, it is through the power of the shamanic rite that the shaman contacts the spirit, reminding it of its vow not to disturb humanity. This rite must be performed in the proper way by reciting the myth that recounts the origin of the rite and making appropriate offerings.

This myth comes from the ancient Bon religion of Tibet. According to the teachings of Dzogchen, the highest spiritual path in that tradition, illnesses and disturbances are deemed to be the result of the imbalance caused by the dualistic vision that arises when a person does not remain in the 'natural' state of mind.

Though conceptualising, negative and stressful emotions arise that afflict man with nervous disorders and physical diseases. However, just like the Native American shamans, the shamans of Tibet hold a different view. They believe the source of the illness to be the energy imbalance that humans create between themselves and all existence, where they provoke the spirits of Nature. To heal people, the Earth and space, it is necessary to contact these spirits, in order to restore balance and re-establish harmonious relationship with them.

These spirits (that humans disturb by their various activities) are the spirits of the five elements (space, air, fire, water, and earth), of the four seasons, and the natural spirits of the Earth, (trees, rocks, mountains, rivers, plants, the sky, sun and moon, stars and clouds, etc.,).

People disturb the sadag (Earth spirits), the nye (tree spirits), and the tsen (rock spirits), by digging the ground, cutting down trees and excavating mountains. They provoke the theurang (space spirits) by polluting the air, and they disturb the lu (water spirits) by polluting rivers and lakes.

This pollution affects people's inner being as well as the environment. By polluting space, they pollute their minds; by polluting fire, they pollute their body heat; by polluting external water, people internally pollute their blood; by polluting the earth, they pollute their bodies.

Shamans do heal adventitious, mental and physical disturbances, though only at a gross level. According to the Bon teachings, ailments are caused either by nad (physical disease) or by a disturbance of vital energy by a don (spirit). The sick person is diagnosed by a doctor to ascertain if the illness has a physical etiology, through urine and pulse tests.

However, if it is found to be due to a provocation of energy by a spirit, then it will be necessary to call a shaman healer. Through divination or astrology, or sometimes through meditation, the shaman will discover the nature of the disturbing spirit and the way to remove it, such as by payment of a ransom.

The founder of the native Tibetan Bon religious tradtion was Tonpa Shenrab Miwoche, and a follower of his teachings is called a Bonpo. An ancient term for a master practitioner of Shenrab's teachings is Shen. Bonpos classify the spiritual teachings and practices Shenrab expounded, in nine ways or vehicles. These are divided into four causal and five resultant ways.

Tibetan Shamanism is found in the first four causal ways. Shamans in Tibet take a very earthy and dualistic approach to life, healing the disturbances and illnesses in this life without being concerned about the next life.

Although their motivation is the altruistic ambition to relieve others' suffering, it lacks the generation of universal compassion that is found in the resultant ways. It is the absence of the cultivation of compassion for all sentient beings, and the aspiration to realise Buddahood as the inspiration for practice, that is the major difference between the causal and resultant ways.

These first four causal ways of the native Tibetan shamans' paths, are called: Chashen (The way of the Shen of Prediction), Nangshen (The Way of the Shen of the Visible World), Trulshen (The Way of the Shen of 'Magical' Illusion), and Sichen (The way of the Shen of Existence).

Chashen, the first way, comprises medical diagnosis and healing, as well as various ancient divination and astrological rites performed by the shaman to determine whether the person who needs to be healed has an energetic imbalance, or is being provoked by a demonic spirit, or negative energy (as mentioned above). Nowadays these rites are still widely practised in Tibetan communitites.

The second way, Nangshen, comprises various rituals for purification to summon energy and enhance prosperity, to suppress and liberate negative forces, and to invoke and make offerings to powerful deities and pay ransoms to demonic spirits.

These practices are very widespread in Tibet. Families perform small ones, while large scale ones are usually performed collectively in towns, villages and monasteries. In ransom rites, an effigy is prepared which represents the beneficiary of the rite, or the shamanic practitioner who is performing it. I remember when my mother had been ill for a long time we tried to heal her by means of different medical treatments, but nothing helped. We then performed several minor rites, but these did not work either. So finally we invited some shaman monks, who performed a big ransom rite, in which they prepared a large effigy of her (in fact, people often make life-size effigies) and we dressed it in her clothes, so that it was very lifelike and resembled her closely. Then we performed the ritual, offering the effigy in her place to repay her karmic debt to spirits. She was given a new name, Yehe Lhamo, in place of her old name, Drolma, as a kind of new birth into the world, and she recovered from her illness.

Shamans of the third way, Trulshen, go where there is strong, wild energy, where they perform practices to conquer the spirits and demons that inhabit those places, subjugating them into their service. One achieves this through practising mantra (words of magic power), mudra (meaningful hand gestures to communicate with gods and spirits), and samadhi (meditation), while performing sadhanas (devotional practices) to engage various wrathful goddesses such as Walmo and Chenmo. The aim of these wrathful practices, which are directed against enemies of the teaching, are to protect the practitioners and the teaching against danger and threats.

It is very important to perform these actions with an attitude of love and compassion towards other beings, and should not be performed solely for the shaman's benefit.

Working with the soul of the living and the dead, is the most important feature of the fourth way, Sichen, which contains a detailed explanation of the principle of the la (soul), yid (mind), and sem (thinking mind). "The la is the karmic trace, which is stored in the kunzhi namshe, (or base consciousness). The sem follows the karmic trace and produces blissful, painful and neutral experiences which are experienced by the yid."

When a living person's soul is lost, shattered, or disordered, there are practices to recall and reinforce its energy, such as soul retrieval. In relation to the dead, there are explanations of 81 different types of death, such as accidental death, suicide, murder, and sinister death.

Following these kinds of death, it is very important to perform appropriate rites, especially if the death occurs in a place which is energetically disturbed (for instance, a place where untoward events such as accidents regularly occur).

A particular specific method found in this way, is that of the 'four doors', to vanquish negative spirits, using 360 different methods. There are also funeral rites to guide the soul immediately after death, communicating with the ghost of the deceased and feeding it until its next rebirth.

One of the most important practices performed by Tibetan shamans of the sichen path is soul retrieval - Lalu (literally redeeming, or buying back the soul), and Chilu, (redeeming the life-energy).

These practices are widespread in the Bon tradition and also in all Tibetan Buddhist schools. One could discuss the soul and life-energy philosophically at great length; but in brief, life energy is the force that keeps mind and body together and the soul is the vital energy of the person. External negativities can cause these two forces to decline, be disturbed, or even lost. Through the lalu and chilu rites, these forces can be recalled, repaired and balanced. To recall the life force in the chilu ritual, the shaman sends out energy as light rays, like a hook, to catch the blessings of the Buddhas; the power of all the protectors, protectresses and guardians; the magic power of all the spirits and eight classes of beings; and the vital energy of the life force of the beings of the six realms. He summons this powerful energy from all the corners of the universe and condenses it into syllables, which he introduces into the disturbed person's heart through his crown chakra, reinforcing his life force.

Shamans perform several different soul retrieval rites. In one rite, a deer - that will recall the soul - is placed on a plate floating in a vase of milk. The shaman then stirs the milk with a dadar (auspicious long life arrow), in order to determine whether the soul has returned. In fact if the deer is facing the house altar when the plate stops turning, the rite has been successful; if it faces the door it has not, and the rite has to be repeated.

In another rite, the beneficiary has to cast white dice on a white cloth, betting against a person of the opposite sign (according to Tibetan astrology), who casts a black dice on a black cloth. When the beneficiary wins this means the rite has been successful.

One of the principle ways of reinforcing the life force is recitation of the mantra of the life deity. The texts say that through this power, the shaman recalls the life force wherever it has strayed. If it is finished, he prolongs it; if it has declined, he reinforces it; if it is torn, he sews it; if it has been severed, he fastens it.

Lalu soul retrieval is performed in a similar way: the shaman summons the spirit which has stolen, or disturbed the person's soul, and offers it a torma (offering cake) representing the union of the five sense pleasures - completely satisfying it with the visualised object, so it will immediately give back the soul it has taken.

There also seems to be a strong connection between the practice of soul retrieval and the popular lungta practice, which is performed to reinforce fortune and capacity, by 'raising the wind-horse'. This is a very powerful rite, performed by large groups of Tibetans, on top of mountains on the first, or third day of the New Year. The participants arouse and invoke the mountain spirits by making smoke offerings, putting up prayer flags and throwing five-coloured cards bearing mantras into space in order to reinforce prana (vital air), which is the support of the la. In this way the la is also healed and reinforced, and consequently the participants' capacity, fortune and prosperity increase, and whatever venture they undertake becomes successful.

These healing rites, in which Bon masters and shamans communicate (either fully conscious or through out-of-the-body experience) with spirits and demons, are widely practiced in all Tibetan Buddhist schools.

It is interesting to note that one of the ways the Buddhist schools attempted to suppress Bon, was by accusing Bon practitioners of being 'intellectually uncivilized' - of being mere primitive shamans. However, in the deepest sense, shamanic belief is the Tibetans' very lifeblood. Tibetans of any religious school who get ill will enact rituals, such as putting up prayer flags, to invoke their guardian spirits and perform ransom rites to remove disturbing spirits, without a moment's hesitation.

Shamanism contains much wisdom that is used to harmonise imbalances, by working on re-establishing good relationships with spirits. The work of Native American shamans in contacting guardian animals for guidance, strength and knowledge, is of great value for healing and for restoring a harmonious relationship with animals, the elements, the sky and the whole environment.

A practitioner of the Bon ways, however, might warn contemporary western shamans about the dangers inherent in certain of the practices they perform

The drum journey, is one such example, used for finding the 'guardian' animal (which they then trust completely) and collaborate with in healing. It is by no means certain that the 'guardian' animal that the shaman meets during the drum journey will be beneficial. In that kind of journey, or out-of-body experience, one can meet hundreds of different beings, just as a non-human being, coming into the human world, will meet hundreds of humans.

The shamanic experience is very important, so it is crucial to have the right guardian, which must be found through real awareness and realisation.

In Tibet most locations, towns and mountains have their own guardian protectors, just as the various religious schools share protective guardian deities. Yet it was yogis, lamas and realised masters who recognised, subjugated and initiated these powerful beings as dharmapalas, or guardians, of the teachings. Until meeting these masters, many of these beings were wild and untrustworthy spirits or the ghosts of evil or confused people, just as the guardian animals the shaman meets may be evil.

In conclusion, it seems to me that many shamans now active in the West focus on working with the emotions and problems of this life, relating with spirits through shamanic drum journeys to heal themselves and others. This practice is very beneficial in curing mental and physical disturbances, and certainly the work shamans do is also very important to restore ecological balance, but it should not remain at that level.

Rather, their work could be enhanced by deepening their knowledge, to obtain comprehension of the nature of mind, and generating the aspiration to engage in contemplative practice to realise Buddhahood. In similar fashion, if the causal means of shamanism were practiced widely in the world, it would be of great benefit for the environment and the world community.

It would be of even greater benefit if all nine vehicles were practiced.

Lama Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche is the founding director of the Ligmincha Institute, a centre devoted to the education of students in the thought and practice of Bon religious teachings and transmissions. He is also a lineage leader of a living Bonpo tradition having received the precious Bon transmissions directly from his teachers, Lopon Sangye Tenzin and Lopon Tenzin Namdak. In particular, he received the entire oral teachings of Zhang Zhung sNyan rGyad. He is the author of 'Wonders of the Natural Mind; the Essence of Dzogchen in the Native Bon Tradition of Tibet' - a newly-published book ,concerned primarily with communicating the Bonpo view of Dzogchen as a spiritual path. Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche also teaches at Rice University and travels widely in the US and Europe giving workshops.

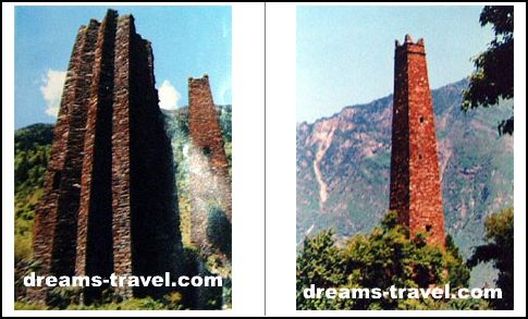

All Along the Watch Tower

Frederique Darragon is a French explorer known for her documentary film The Secret Towers of the Himalayas, which chronicled her expedition of the mystifying stone towers of Sichuan and Tibet.....old stone towers, some vaguely star-shaped and some more than 100 feet tall, scattered across the foothills of the Himalayas. Yet when she asked local residents about the towers—Who built them? When? Why?—nobody seemed to have a clue.......they were built 500 to 1,100 years ago......One structure in Kongpo, Tibet, a day's drive from the capital, Lhasa, proved much older. It was likely built between 1,000 and 1,200 years ago, before Mongolian tribes invaded Tibet, around 1240....

Darragon was especially intrigued by the more than 40 roughly star-shaped towers she encountered. Some have 8 points, others 12. In both configurations, star-shaped towers are rare, scholars say. At least two others can be found in Afghanistan, including the Minaret of Bahram Shah in Ghazni.

Why were they built? One idea is they served a religious function, perhaps representing the dMu cord that, according to Tibetan legend, is said to connect heaven and earth. "The towers might actually symbolize this cord," says Bianca Horlemann, an independent Tibet scholar....

Darragon found that many of the villages where the towers are located bear the same names as 18 kingdoms described previously only in legends.

According to Bon tradition of Tibet, Tibet had written language several hundred years before the time of Emperor Stongsten Gampo. Professor Namkha's Norbu has documented that in his book called Neclace of Dzi. The legend has it that ancient Bon kings would climb up the stair to the heaven when they are about to die. This could be some form of sky burial for the kings and nobels of the time.

The natives had a strange name for the towers . . . bdud khang, or "demon houses." All were open structures, most had window type openings at different levels, and were several floors or stories tall. No one knew why they were built or who make them.....The Kongpo people consider themselves Tibetan. "They all believe in the creation myth of the children of the she-demon and the monkey....The contemporary Jiarong and Minyag people as well as the Tamang of Nepal, who are also Buddhist, and the Qiang Zu, who are not Buddhist, also believe in the same creation myth.

The so-called "demon-towers" (bdud khang) of Kongpo which I visited in 19967 are interestingly shaped as twelve cornered mandalas and clustered in groups of three. These towers are believed to have been built, not by humans, but by aChung, the king of demons in the Gesar Epic. R.A. Stein writes in The World in Miniature how "such dwellings and defence towers are noted by Chinese texts from the Han, Sui, and T´ang (second to eighth centuries) in connection with independent kingdoms and peoples of Tibetan stock.....In many cases, ancient stone masonry in Bhutan and Tibet appears to be of quite astounding quality, which may contribute to the common belief that some of these old structures were built by non- humans.

The Ideal of Nine Stories Many of the old tower structures may originally have had nine floors, as this is an ideal, auspicious number with ancient roots in shamanistic mythology. Such symbolism is also described by Stein explaining how this ideal was applied to a vertical hierarchy revealed by the number of stories; "The king (or queen) had as many as nine, the people up to six."

A similar numerology is also reflected in an old Bönpo (bon po) text from the twelfth century published by Samten Karmay which relates how palaces are to be organized.This text describes how various functions are to be adapted horizontally within a 3x3 pattern, according to an ideal which buildings were striving to achieve. By following "the rules of Shenrab, the radiant clarity will cause blessings to descend." The buildings would then please the gods and attract divine presence.

Watchtower in Shuopo township Rongzhag is famous for "Thousand stone castle kingdom"with many kinds of old stone castles (watchtower, "Qionglong" in ancient) scattered over the county, Built as early as 1700BC, the watchtowers in Shuopo village varies greatly.

The height of watchtowers are between 16 and 35 meters, they stand on hillsides or the top of hills with stone slabs for their walls and stone blocks for their foundations. Usually the watchtowers there are designed as polygonal shapes, such as square, pentagon, hexagon, and octagon etc. The best ones have 13 sides and serve as watchtower pearls in Damba area (only 3 13-sided watchtowers left in Gyarong Tibetan area). There are four kinds of watchtowers in Rongzhag according to their different use: Strategic Pass, Beacon-Fire, Village and Dwelling, most of them are well protected.

Danba has preserved four kinds of watchtowers: Yao`ai (Strategic Pass), Fenghuo (Beacon-Fire), Zhai (Village), and Jia (Dwelling). The Yao‘ai watchtower was built at passes and places of strategic importance. "If one man guards the pass, ten thousand can not get through"; and these watchtowers are testaments to this old Chinese saying. The Fenghuo watchtower was built on hilltops for the purpose of transmitting messages. To protect inhabitants and property, the Zhai watchtower was built at the entrance of villages. The Jia watchtower was built inside the village and was connected to the dwelling houses. It was used as storage in peacetime and as a defense during wartime. All of the watchtowers in Danba have a door fitted about five meters above their foundation; and people must climb a wooden ladder to get into them. When the villages were invaded, people hid in the watchtowers. They drew back the ladder and closed the door so that the invaders could do nothing against them. The watchtowers also have apertures from which archers could shoot at invaders.

Darragon was especially intrigued by the more than 40 roughly star-shaped towers she encountered. Some have 8 points, others 12. In both configurations, star-shaped towers are rare, scholars say. At least two others can be found in Afghanistan, including the Minaret of Bahram Shah in Ghazni.

Why were they built? One idea is they served a religious function, perhaps representing the dMu cord that, according to Tibetan legend, is said to connect heaven and earth. "The towers might actually symbolize this cord," says Bianca Horlemann, an independent Tibet scholar....

Darragon found that many of the villages where the towers are located bear the same names as 18 kingdoms described previously only in legends.

According to Bon tradition of Tibet, Tibet had written language several hundred years before the time of Emperor Stongsten Gampo. Professor Namkha's Norbu has documented that in his book called Neclace of Dzi. The legend has it that ancient Bon kings would climb up the stair to the heaven when they are about to die. This could be some form of sky burial for the kings and nobels of the time.

The natives had a strange name for the towers . . . bdud khang, or "demon houses." All were open structures, most had window type openings at different levels, and were several floors or stories tall. No one knew why they were built or who make them.....The Kongpo people consider themselves Tibetan. "They all believe in the creation myth of the children of the she-demon and the monkey....The contemporary Jiarong and Minyag people as well as the Tamang of Nepal, who are also Buddhist, and the Qiang Zu, who are not Buddhist, also believe in the same creation myth.

The so-called "demon-towers" (bdud khang) of Kongpo which I visited in 19967 are interestingly shaped as twelve cornered mandalas and clustered in groups of three. These towers are believed to have been built, not by humans, but by aChung, the king of demons in the Gesar Epic. R.A. Stein writes in The World in Miniature how "such dwellings and defence towers are noted by Chinese texts from the Han, Sui, and T´ang (second to eighth centuries) in connection with independent kingdoms and peoples of Tibetan stock.....In many cases, ancient stone masonry in Bhutan and Tibet appears to be of quite astounding quality, which may contribute to the common belief that some of these old structures were built by non- humans.

The Ideal of Nine Stories Many of the old tower structures may originally have had nine floors, as this is an ideal, auspicious number with ancient roots in shamanistic mythology. Such symbolism is also described by Stein explaining how this ideal was applied to a vertical hierarchy revealed by the number of stories; "The king (or queen) had as many as nine, the people up to six."

A similar numerology is also reflected in an old Bönpo (bon po) text from the twelfth century published by Samten Karmay which relates how palaces are to be organized.This text describes how various functions are to be adapted horizontally within a 3x3 pattern, according to an ideal which buildings were striving to achieve. By following "the rules of Shenrab, the radiant clarity will cause blessings to descend." The buildings would then please the gods and attract divine presence.

Watchtower in Shuopo township Rongzhag is famous for "Thousand stone castle kingdom"with many kinds of old stone castles (watchtower, "Qionglong" in ancient) scattered over the county, Built as early as 1700BC, the watchtowers in Shuopo village varies greatly.

The height of watchtowers are between 16 and 35 meters, they stand on hillsides or the top of hills with stone slabs for their walls and stone blocks for their foundations. Usually the watchtowers there are designed as polygonal shapes, such as square, pentagon, hexagon, and octagon etc. The best ones have 13 sides and serve as watchtower pearls in Damba area (only 3 13-sided watchtowers left in Gyarong Tibetan area). There are four kinds of watchtowers in Rongzhag according to their different use: Strategic Pass, Beacon-Fire, Village and Dwelling, most of them are well protected.

Danba has preserved four kinds of watchtowers: Yao`ai (Strategic Pass), Fenghuo (Beacon-Fire), Zhai (Village), and Jia (Dwelling). The Yao‘ai watchtower was built at passes and places of strategic importance. "If one man guards the pass, ten thousand can not get through"; and these watchtowers are testaments to this old Chinese saying. The Fenghuo watchtower was built on hilltops for the purpose of transmitting messages. To protect inhabitants and property, the Zhai watchtower was built at the entrance of villages. The Jia watchtower was built inside the village and was connected to the dwelling houses. It was used as storage in peacetime and as a defense during wartime. All of the watchtowers in Danba have a door fitted about five meters above their foundation; and people must climb a wooden ladder to get into them. When the villages were invaded, people hid in the watchtowers. They drew back the ladder and closed the door so that the invaders could do nothing against them. The watchtowers also have apertures from which archers could shoot at invaders.

Tibet's Dragon Culture http://www.tibetinfor.com/english/services/forum/for_003.htm

In China, the image of the dragon is known to everyone; in fact, the Chinese people are called "descendants of the dragon." In the Chinese people's eyes, the Yangtze River, the Great Wall and the Yellow River are symbols of dragons, and the year 2000 is the Year of the Dragon by the traditional lunar calendar.

Dragon-Deity in the Land of Snow

"Zhug" means "dragon" in the Tibetan language. In Tibetan mythology and culture, Zhug is a deity, and the ancient Tibetans thought that thunder and hailstones were caused by Zhug, who resided in the clouds.

Following the beginning of cultural exchanges between the Han and Tibetan peoples in the time of the Tubo Kingdom of Tibet and China's Tang Dynasty (618-907), the image of the dragon was introduced from the Central Plains area to Tibet. They became identified because Zhug and the Dragon were both supposed to be in charge of rainfall. Finally, the concept of the dragon spread all over the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and became known to every household, adding a new image to Tibetan Buddhist art.

About Zhug's original image and meaning, opinions are widely divided. Folklore has it that it evolved from the story of a snake. According to a legend, a snake in a remote deep valley turned into a dragon and finally soared into the sky. This version is similar to one common in the Central Plains area. According to Tibet's native Bon religion, the image of Zhug was created by people 4,000 years ago and associated with water. The dragon represents water as one of the four elements (earth, fire, wind and water). This influence may ultimately derive from India.

Dragons in Sculptures and Paintings

As an artistic image, the dragon has been used widely in Tibetan architectural decorations, in which it is one of the most common motifs. According to Tibetan historical records, as early as during the Tubo Kingdom temples such as the Samyai Monastery housed gold and jade sculptures of dragons. When Lin Yuanding, a Tang Dynasty envoy, visited Tibet, he saw decorations of golden dragons in the tent of the Tubo king. The stone tablet at Chido Songtsan's tomb has dragons carved on it, and in the ruins of the ancient Guge Kingdom discovered in Ngari, people have found carvings depicting dragons as well as horses.

In famous lamaseries of the later period people can see images of dragons everywhere, and the dragon eventually became a component part of Tibetan Buddhist art. For instance, in the mural, Guardian King of the East, which is on the wall inside the East Gate of the Potala Palace, over the head of the Heavenly King there are two dragons, and in between is a pearl; the whole being similar to the pattern of "two dragons playing with a pearl" of the Han people. The Heavenly King is a guardian deity introduced from India, and of course his image has traces of Indian influence. But the mural is not in pure Indian style, as it has typical images of dragons popular in the Central Plains area. Pillars with dragons coiling around them in front of Buddhist statues can be found in some large temples, and these are also in the architectural style of the Central Plains area. For instance, the two dragons coiling around the pillars in front of the statue of Sakyamuni in the Jokhang Monastery in Lhasa are very eye-catching. The two dragons bare their fangs, brandish their claws and glare at each other. On the pillars in front of the statue of Guanyin (Goddess of Mercy) in the Sage Hall are also two dragons, which are vivid and lifelike. In addition, the images of dragons can also be found on thrones, Tangka icons, Tibetan carpets, pillars and embroidery, and in bedrooms and on the bedclothes of living Buddhas.

In short, dragon motifs can be found everywhere in Tibetan Buddhist art. They have been favorite themes, since the dragon is a symbol of auspiciousness and nobility.

The Green Dragon in Tibetan Epics

In Tibetan folk tales, legends and epics, "Zhug" is mentioned frequently, and is known as the "Zhug-deity." The sound of thunder in the Tibetan language is called the sound of "Zhug," and the Tibetans believe that Zhug resides in clouds in the sky. A line from a Tibetan song reads, "Seeking luck in the sky, I happen to meet the Green Dragon, and three roads lead to the luck of the Green Dragon." In the epic King Gesar, the dragon is mentioned in many places. Because the dragon is the God of Thunder, symbolizing bravery and all-conquering force, it is also used as a synonym for a hero. For instance, a verse in the chapter "Subduing the Demons" of King Gesar reads, "In the blue sky there is a jade dragon. He lives in Purple Cloud City. He roars to show his might, and he throws a thunderbolt like an arrowhead. In one blow he destroys the eagle's nest, and in another he smashes the Red Rock Peak."

After Princess Wencheng of the Tang Dynasty went to Tibet to marry the king of Tubo, in explaining the geomantic configuration of Lhasa, she said that to the east of Huotang

Lake was a tiger, to the south of it was a green dragon, to the west was a scarlet bird, and to the north was a tortoise. In King Gesar, the dragon was said to reside in the south, which is similar to the traditional geomantic configuration in the Central Plains area.

The Dragon and Names of Places and People

As the dragon has connotations of nobility and power, it is often used in the names of people and places. In the Gannan Tibetan Prefecture, Gansu Province, there is a river called Zhugqu, meaning Dragon River; its Chinese name is Bailong (White Dragon) River. It is thus named because its place of origin, a mountain cave in northwestern Sichuan Province, has two white stones which are shaped like dragons. Along the river there is a county called Zhugqu, which is named after the river.

The name of the wife of King Gesar, Sengjam Zhugmo, means "dragon's daughter." It is said that when she was bom a dragon's rumblings were heard in the sky. Now many Tibetan women are named "dragon's daughter."

In Tibetan Buddhism there is a sect named after the dragon, that is Zhugba Karju. The temple of this sect is called Zhug Temple, meaning Dragon Temple. The modern South Zhugba Sect is mainly active in Bhutan, which has many people of Tibetan stock. The dragon is also one of the most popular themes in the art works of Bhutan.

The Dragon and the Calendar

Ancient Tibetans used a combination of five elements (metal, wood, water, fire and earth) and 12 symbolic animals (rat, ox, tiger, hare, dragon, snake, horse, sheep, monkey, cock, dog, and hog) to identify the years. Historical documents unearthed from Dunhuang record the way of numbering years according to the 12 symbolic animals, and the Year of the Dragon is called "Zhuglo." Although people's opinions on the origin of the 12-year cycle vary, in areas inhabited by large number',: of Tibetans this traditio~ has a long history. This indicates that the concept of Zhug appeared very early in Tibetan culture.

Naga and Lu

Besides Zhug, deities similar to the Dragon-deity include Naga of Buddhism and Lu of the Bon religion. Both are translated as long in Chinese, meaning "dragon."

The Dragon in Buddhism. In Buddhist scriptures there are more than 28,000 dragon kings, and they have many relatives. Most dragon kings dwell in the sea, and have luxurious palaces. The images of dragons on unearthed sculptures are personified. The Dragon King sits on the throne, and over his head there is a canopy formed of snake heads; to his left and right are musicians and servants. There is a relief sculpture called The Dragon King and His Wife Drinking Wine. The Dragon King and his wife are depicted sitting in the center holding wine cups. They are flanked by servant girls ready to pour wine for them. In the art works of Tibetan Buddhism, the image of Naga is also personified. For instance, in the mural The Dragon King Presents Treasure, a dragon king from the sea is presenting a treasure to the Buddha. The image of the dragon king often represents a king or other benefactors in Buddhist paintings. On the backs of many Buddhist statues are painted portraits of the dragon's daughter, half-woman and half-snake.

The Dragon in the Bon Religion. Lu in the doctrines of Bon is a deity dwelling in the world of mortals. Similar to Naga in Buddhism, Lu dwells in rivers, lakes or underground. Animals related to Lu include snakes, fish and frogs. Lu has many different images in Bon scriptures and temples. He has a human body with the head of a snake, a horse, a pig, a deer or a lion. Common to all these concepts is the tail of a snake. It is said that Lu can transform itself into a snake, so Lu worship probably originated in primitive snake worship. According to Bon doctrines, Lu is in charge of land and rainfall, so the Bon followers dare not dig in the earth around a house, for fear of offending Lu. Monks often perform rituals in honor of Lu, especially in seasons of drought, as Lu controls the rainfall, or to cure a patient who is thought to have fallen ill as a result of offending Lu.

Zhug and Lu among Tibetans

Among the Tibetan people, Zhug is regarded both as an auspicious deity and a tyrant who pelts the earth from time to time with hail. In Lintan County, Gansu Province, there is a lake called Ama Zhugco, meaning "Mother Dragon Lake," or Zhugmoco, meaning "Dragon's Daughter Lake." Obviously, the Tibetans regard this lake as the dwelling of Zhug, and the deity is referred to as "she." Every year, a sacrificial ritual is held there.

Lu is also regarded as a deity in charge of land, rivers, lakes, springs, and rainfall. Famous lakes are considered to be the dwellings of dragon kings. Lu can also spread diseases, such as leprosy. Therefore, the Tibetans forbid the pollution of waters and the digging of earth. Snakes, frogs and fish are also considered to be deities, and it is forbidden to harm them.

People show different attitudes toward Zhug and Lu; they are more fearful of Lu. When building temples, they hold a ceremony to worship the God of the Land, who is one personification of Lu.

The statue of Maizhog Serqen, or the dragon's daughter, can be found in Lhasa. She used to be a local deity. Later, she was subdued by Padmasambhava and became a guardian of Buddhism. She is worshipped by believers in several sects of Tibetan Buddhism, including the Ningma, Kargyu and Gelug sects.

In China, the image of the dragon is known to everyone; in fact, the Chinese people are called "descendants of the dragon." In the Chinese people's eyes, the Yangtze River, the Great Wall and the Yellow River are symbols of dragons, and the year 2000 is the Year of the Dragon by the traditional lunar calendar.

Dragon-Deity in the Land of Snow

"Zhug" means "dragon" in the Tibetan language. In Tibetan mythology and culture, Zhug is a deity, and the ancient Tibetans thought that thunder and hailstones were caused by Zhug, who resided in the clouds.

Following the beginning of cultural exchanges between the Han and Tibetan peoples in the time of the Tubo Kingdom of Tibet and China's Tang Dynasty (618-907), the image of the dragon was introduced from the Central Plains area to Tibet. They became identified because Zhug and the Dragon were both supposed to be in charge of rainfall. Finally, the concept of the dragon spread all over the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and became known to every household, adding a new image to Tibetan Buddhist art.

About Zhug's original image and meaning, opinions are widely divided. Folklore has it that it evolved from the story of a snake. According to a legend, a snake in a remote deep valley turned into a dragon and finally soared into the sky. This version is similar to one common in the Central Plains area. According to Tibet's native Bon religion, the image of Zhug was created by people 4,000 years ago and associated with water. The dragon represents water as one of the four elements (earth, fire, wind and water). This influence may ultimately derive from India.

Dragons in Sculptures and Paintings

As an artistic image, the dragon has been used widely in Tibetan architectural decorations, in which it is one of the most common motifs. According to Tibetan historical records, as early as during the Tubo Kingdom temples such as the Samyai Monastery housed gold and jade sculptures of dragons. When Lin Yuanding, a Tang Dynasty envoy, visited Tibet, he saw decorations of golden dragons in the tent of the Tubo king. The stone tablet at Chido Songtsan's tomb has dragons carved on it, and in the ruins of the ancient Guge Kingdom discovered in Ngari, people have found carvings depicting dragons as well as horses.

In famous lamaseries of the later period people can see images of dragons everywhere, and the dragon eventually became a component part of Tibetan Buddhist art. For instance, in the mural, Guardian King of the East, which is on the wall inside the East Gate of the Potala Palace, over the head of the Heavenly King there are two dragons, and in between is a pearl; the whole being similar to the pattern of "two dragons playing with a pearl" of the Han people. The Heavenly King is a guardian deity introduced from India, and of course his image has traces of Indian influence. But the mural is not in pure Indian style, as it has typical images of dragons popular in the Central Plains area. Pillars with dragons coiling around them in front of Buddhist statues can be found in some large temples, and these are also in the architectural style of the Central Plains area. For instance, the two dragons coiling around the pillars in front of the statue of Sakyamuni in the Jokhang Monastery in Lhasa are very eye-catching. The two dragons bare their fangs, brandish their claws and glare at each other. On the pillars in front of the statue of Guanyin (Goddess of Mercy) in the Sage Hall are also two dragons, which are vivid and lifelike. In addition, the images of dragons can also be found on thrones, Tangka icons, Tibetan carpets, pillars and embroidery, and in bedrooms and on the bedclothes of living Buddhas.

In short, dragon motifs can be found everywhere in Tibetan Buddhist art. They have been favorite themes, since the dragon is a symbol of auspiciousness and nobility.

The Green Dragon in Tibetan Epics