Serpent Worship in Europe

Due to its unique characteristic represented by the cyclical shedding of its skin,

the serpent was the Druid symbol of rebirth

the serpent was the Druid symbol of rebirth

Also see, Return of the Serpents of Wisdom

http://books.google.com/books?id=46Hfa0Ss-kIC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

SONS OF THE SERPENT TRIBE

http://www.bibliotecapleyades.net/sumer_anunnaki/reptiles/serpent_tribe/serpent_tribe.htm

SERPENT WORSHIP

http://books.google.com/books?id=R8qAAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=serpent+worship&source=bl&ots=PvN6nnKCEy&sig=OOhf8Gq9I-TSO-oCNXlB9O5cpbE&hl=en&ei=jVS_TcjfMpDWtQPJs4nQAw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=14&sqi=2&ved=0CGEQ6AEwDQ#v=onepage&q&f=false

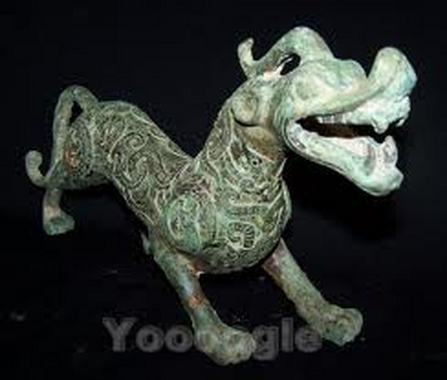

FLYING SERPENTS & DRAGONS

http://books.google.com/books?id=2TtOjwtbXG8C&printsec=frontcover&dq=FLYING+SERPENTS+and+DRAGONS+by+R.A.+Boulay&hl=en&src=bmrr&ei=TEYTTpbSC-HjiAKnmpDuDQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CDQQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=FLYING%20SERPENTS%20and%20DRAGONS%20by%20R.A.%20Boulay&f=false

SONS OF THE SERPENT TRIBE

http://www.bibliotecapleyades.net/sumer_anunnaki/reptiles/serpent_tribe/serpent_tribe.htm

SERPENT WORSHIP

http://books.google.com/books?id=R8qAAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=serpent+worship&source=bl&ots=PvN6nnKCEy&sig=OOhf8Gq9I-TSO-oCNXlB9O5cpbE&hl=en&ei=jVS_TcjfMpDWtQPJs4nQAw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=14&sqi=2&ved=0CGEQ6AEwDQ#v=onepage&q&f=false

FLYING SERPENTS & DRAGONS

http://books.google.com/books?id=2TtOjwtbXG8C&printsec=frontcover&dq=FLYING+SERPENTS+and+DRAGONS+by+R.A.+Boulay&hl=en&src=bmrr&ei=TEYTTpbSC-HjiAKnmpDuDQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CDQQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=FLYING%20SERPENTS%20and%20DRAGONS%20by%20R.A.%20Boulay&f=false

The Serpent N’H’SH

In translating the word N’H’SH, firstly we will take the Hebrew consonants back, via Phoenician, to their Sumerian roots and remember also that, in Sumerian, syllable groups could be reversed and yet still render the same meaning in an overall phrase. So, the N is Nun, the H is Heth (as opposed to He) and the SH is Shin (as opposed to either Sade or Samekh).

We check these through the Phoenician to ensure a continuity of shape in the correct pictograms as we venture back into the Sumerian and discover the following: Nun = Nag, Heth = H.A. and Shin = Salmunuz. Therefore from the Hebrew Nahash, we derive the original Sumerian Naghasalmunuz, Nagha Salmunuz or NAG.HA.SAL.MUNUZ., which translates as Drink (NAG) - Fish (HA) - Vulva (SALMUNUZ).

If this sounds a bit odd, the author explains that a fish is "of water" and so in Sumerian the equivalent to our letter ’A’ means water whilst the ’H’ is the article which stands for of. So the Hebrew N’H’SH - the Serpent - translates into the Sumerian "One (a dragon) who - Drinks of (the) Water (of the) Vulva".

One notices that in this phrase - Nagha Salmunuz - two things stand out. Firstly we have the Aryan word Naga spelt Nagha which would be pronounced with the gh sounding like a nasally, softly gargled ch (as in the Scottish word loch) identical to the Spanish x or g. According to the OED, ’H’ which in Sumerian was H.A. evolved into the Greek h - (h)eta which was originally pronounced kh, which was pronounced as defined above, as an Iberian (Aryo-Scythian Celtic) x or ch.

In this way we can also justifiably spell Naga as Naxa and then we begin to understand the profound relationship between the Naga guardians of the Aryan pantheons and the Nixes or Nixas of western Europe who were, likewise, the female guardians of watery treasures, and like the Nagas or Naxas, these meremaids or Swan Maidens were Devas or Shining Ones (Anunnagi).

The second thing we notice is that the Sumerian word for a vulva is Salmunuz and immediately the poetic connection between the ’Sacred Vulva’ (the well of Nechtan [Nixtan] - the pure one, the Nix or Nothing) and the Salmon (Salmunuz) of Wisdom that swims in the well should immediately spring to mind - as should the Ichthys - as being the vulva of the Virgin Mary Magdalene. Praise the Lord for the Single Poetic Theme!

In remembering that Sumerian can be reversed, we can look at the Hebrew N’H’SH again and see that if it is reversed, as was the custom in Hebrew Qabalah when rabbis were tinkering around with language looking for hidden meanings, it becomes SH’H’N which is pronounced She’an, ’of the Powers’. Furthermore the numerical or gematric value of N’H’SH in Qabalah is 9 which is the number of Yesod, the sephirah of the Moon, whose Phoenician God was the Sumerian SIN or SHIN - She’en.

The symbols associated with SIN included the Axe, the Labrys which is a device which, as we know, depicts the Vulva. The Axe symbol, prevalent in Mittani and Minoan Cretan culture became the spinning Hammer of Thor (the swastika) who as Zeus, was the wielder of the lightning bolt which, in northern Europe, was symbolized by the Norse ’Sig’ Rune. Sig - the lightning bolt of inspiration (cf. Mead of Inspiration) - is the Greek Sigma which is the Hebrew Shin, last consonant of N’H’SH, and SIN - Sumerian god of the Moon.

Sig is the serpentine lightning bolt that courses down the Qabalistic Tree of Life. In one sense it represents Enki-Samael entwined around Lilith. The upturned crescent moon is also said to be associated with Samael (Sumaire-El) and, in an ancient Sumerian picture reproduced by Langdon, the moon as a dish is depicted next to the Star of Anu, below which is the serpent N’H’SH entwined around the tree, symbolizing Lilith.

Finally we must consider Tiamat. Her name - TI.A.MAT - means life-water-maiden. This translates as "maiden of the waters of life" and it is then clear that her name indicates she was both the first known matriarch and virgin priestess - the "feeding mother" - of the vampire dragon queens and kings. The mother of the Elven dynasty, she was the generatrix of a vampire lineage of goddess-queens and god-kings spanning seven thousand years.

She was a Nagha or Nixa and it is from her that Lilith, and all the ensuing Grail Maidens, including Sheba and Morgana of the Apple Trees, Tamaris, Mary Magdalene, the Princesses of Avallon, Melusine, Niniane and Ygraine owe their identifications as "Trees of Life". Consequently we can say that Tiamat, the first Tamaris - the Maiden who gives the Waters of Life - was also the Tir Mat or Tir Mata, the first "Tree Mother" of the Lords and Ladies of the Forest, the Druids and Druidesses - the People of the Trees (of Life).

Of the younger gods of the Aryans, the Adityas, two - Tara and Bhaga - stand out prominently. As we have seen Ulick Beck and several other scholars have traced the origin of the Scythian-Irish Tuadha d’Anu to the same region as the Aryans, and have gone as far as saying that they were one and the same.

Interestingly we find that the goddess Tara - wife of Rudra, Indra’s charioteer, appears in Eire as Tara, the Hill or Rath of ghosts in County Meath, Eire. Tara was the sacred centre of the united Irish kingdom and was the seat of the Danaan Kings of Tara during the Iron Age.

Some scholars attribute the name of Tara in Eire to some complicated sounding god name which I find implausible in the light of the fact that a Goddess Tara already existed in the Scythian-Aryan pantheon. Whether Asura or Aditya, Danaan or Milesian, all of the ancient Goddess Queens were the source of sovereignty associated with sacred mounds and it seems therefore entirely appropriate to name a Sidhe rath, a portal to the otherworld and thus the source of sovereignty, after a goddess who would herself have represented sovereignty.

In the case of Bhaga, or Vaga as his name would have been pronounced in Gaelic, scholars think that he became the Slavic god Bogh, a word which came to mean "god" in Thrace, where the Danaan Fir Bolg were once exiled, prior to their return to Ireland. In Fir Bolg we either have the title "men of God", meaning druids, or we have, as is commonly thought, "men of the bags" which means "men of God" anyway, because the "bag", specifically the "Crane Skin Bag", was an accessory of the Godthi’s and the Druid’s: the "men of the gods".

Serpent Worship in Europe

SERPENT-WORSHIP IN EUROPE.

I. GREECE.--Whether the learned and ingenious Bryant 1 be correct or not, in deriving the very name of EUROPE from אור־אב (AUR-AB), the solar serpent, it is certain that Ophiolatreia prevailed in this quarter of the globe at the earliest period of idolatry 2.

Of the countries of Europe, Greece was first colonized by Ophites, but at separate times, both from Egypt and Phœnicia; and it is a question of some doubt, though perhaps of little importance, whether the leader of the first colony, the celebrated Cadmus, was a Phœnician or an Egyptian. Bochart has shown that Cadmus

p. 184

was the leader of the Canaanites who fled before the arms of the victorious Joshua; and Bryant has proved that he was an Egyptian, identical with THOTH. But as mere names of individuals are of no importance, when all agree that the same superstition existed contemporaneously in the two countries, and since Thoth is declared by Sanchoniathon to have been the father of the Phœnician as well as Egyptian Ophiolatreia; we may endeavour, without presumption, to reconcile the opinions of these learned authors, by assuming each to be right in his own line of argument; and by generalizing the name CADMUS, instead of appropriating it to individuals. By the word CADMUS, therefore, we may understand the leader of the CADMONITES, whether of Egypt or Phœnicia. There would, consequently, be as many persons of this name, as colonies of this denomination.

The first appearance of these idolaters in Europe is mythologically described under the fable of "Cadmus and Europa;" according to which, the former came in search of the latter, who was his sister, and had been carried off to Europe by Jupiter in the form of a bull.

If EUROPA be but a personification of the

p. 185

[paragraph continues] SOLAR SERPENT-WORSHIP, and CADMUS a leader of serpent-worshippers, the whole fable is easily solved.

Europa was carried by Jupiter to Crete, where she afterwards married ASTERIUS: that is, the SOLAR SERPENT-WORSHIP was established in Crete, and afterwards united with the worship of the HEAVENLY HOST: Asterius being derived from ἀστὴρ, a star.

For the explanation of that portion of the fable which relates to the BULL, the reader is referred to Bryant, Anal. vol. ii. 455, who thinks that it bore an allusion to the god APIS of Egypt, by whose oracular advice the migration was undertaken. A similar worship, however, prevailed in Syria; for we find that the Phœnician Cadmus, (Cadmus the son of Phœnix), when he went in search of his sister, followed a cow. This latter colony is said to have settled in Eubœa; to which they gave the name of their tutelary deity, AUB; for Eubœa is, according to Bryant, AUB-AIA, "the land of AUB 1."

The history of Cadmus is full of fables about serpents. He slew a dragon, planted its teeth, and hence arose armed men, who destroyed each other until five only remained. These assisted him in building the city of THEBES. One of these five builders of Thebes was named after the serpent-god of the Phœnicians, OPHION.

Cadmus, and his wife Harmonia, finished their travels at Encheliæ in Illyricum, where, instead of dying a natural death, they were changed into serpents. This conclusion of the story throws a light upon the whole. The leader of these Opiates after death was deified, and adored under the symbol of a serpent. He became, in fact, the SERPENT-GOD of the country, as Thoth had become the serpent-god of Egypt. Having been the author, he became the object of the idolatry.

Besides the Cadmian colony, which settled chiefly in Bœotia, a second irruption of Ophites is noticed in history, as coming from Egypt under the guidance of CECROPS. These took possession of Attica, and founded Athens, whose first name was, in consequence, CECROPIA. In this word, also, we trace the involution of the name OB, or OPS, the serpent-god of antiquity; and accordingly, Cecrops 1 himself is said to have been of twofold form, human and serpentine 1. It was also said, that from a serpent he was changed into a man 2. We read too of DRACO (Δράκων, a dragon) being the first king of Athens. All these relate to the introduction of serpent-worship from Egypt into Attica, the leader of which colony, by a fabulous metonyme, was called a "dragon," or serpent. The first altar erected by Cecrops at Athens, was to OPS, the serpent-deity 3; a circumstance which confirms the inference deduced by Bryant; namely, that he introduced Ophiolatreia into Attica. Cecrops and Draco were probably the same person.

2. The symbolical worship of the serpent was so common in Greece, that Justin Martyr accuses the Greeks of introducing it into the mysteries of all their gods. Παρὰ παντὶ τῶν νομιζομένων παῤ ὕμῖν θεῶν Ὄφις

σύμβολον μέγα καὶ μυστήριον ἀναγράφεται 1 [paragraph continues] This was especially true in regard to the mysteries of Bacchus. The people who assisted at them were crowned with serpents, and carried them in their hands, brandishing them over their heads, and shouting with great vehemence, ευια, ευια 2; "which being roughly aspirated," remarks Clemens Alexandrinus, "will denote the female serpent 3." A consecrated serpent was a sign of the Bacchic orgies 4; a very important part of which consisted in a procession of noble virgins, carrying in their hands golden baskets, which contained sesamum, small pyramids, wool, honey-cakes, (having raised lumps upon them like navels), grains of salt, and A SERPENT 5.

Three ingredients in these baskets are remarkable, as connected with THE WORSHIP OF THE SOLAR SERPENT.

1. The pyramids, which were intended as representations of the sun's rays, and are sometimes seen in the hands of priests kneeling before the sacred serpent of Egypt 1. The supplicating minister of the god offers a pyramid in his left hand, while the right is field up in adoration. On his head is the deadly asp.

2. The honey-cakes marked with the sacred omphalos. These were also offerings made at the shrine of the sacred serpent; for we read in Herodotus, that in the Acropolis at Athens was kept a serpent who was considered the guardian of the city. He was fed on cakes of honey once a month 2. The serpent of Metele was presented with the same food or offering 3. Medicated cakes, in which honey was a chief ingredient, were at once the food and the offering to the dragon of the Hesperides--

------------- Sacerdos

Hesperidum templi custos, epulasque draconi

Quæ dabat, et sacros servabat in arbore ramos,

Spargens humida mella, soporiferumque papaver.

Virgil, i n. iv. 483. A similar offering was made to Cerberus, by the prophetess who conducted Æneas

Cui vates horrere videns jam colla colubris

Melle soporatam et medicatis frugibus offam

Objicit ----------

Æn. vi. 419. [paragraph continues] Honey cakes were also carried by the initiated into the cave of Trophonius to appease the guardian serpents 1. So that this offering was universally peculiar to Ophiolatreia.

The honey-cake, however, when properly pre-pared, was marked with the sacred Omphalos--a remarkable peculiarity on which it may be proper to make a few observations.

The superstition of the OMPHALOS was extensively prevalent. It entered into the religions of India and Greece, and is one of the most figurative and obscure parts of mythology. The omphalos is a boss, upon which is described a spiral line; but whether or not this spiral line may have been originally designed to represent a coiled serpent, I will not pretend to determine; though such a meaning has been affixed to it by an ingenious writer 1 upon the antiquities of New Grange in Ireland. In describing similar lines upon some rude stones discovered at this place, he tells us, "they appear to be the representations of serpents coiled up, and probably were symbols of the Divine being." "Quintus Curtius confirms this hypothesis, when he says, that the temple of Jupiter Ammon in Africa had a rude stone, whereon was drawn a spiral line, the symbol of the deity."

Whatever may have been the meaning of this spiral line, which Quintus Curtius calls a navel, one thing is evident, that the omphalos, umbilicus, or navel, was sacred to the serpent-god: for it not only occurs in the mystic baskets of the Bacchic orgies, but was also kept at DELPHI 2, "because," says Pausanias, "this was the middle of the earth." The absurdity of this notion at once refers us to some better reason; but absurd as it is, the same idea seems to have prevailed generally; for we read of an omphalos of the Peloponnesus at Phlius, in Achaia: "if it be as they say," adds the incredulous topographer 1.

Near the latter omphalos was a temple of BACCHUS, another of APOLLO, and another of ISIS, to each of which deities the serpent was sacred. The sacred omphalos, therefore, would seem to bear very much upon the adoration of the serpent; and it is a question whether or not it was originally intended to represent a coiled serpent as symbolical of divinity.

The esoteric tradition of the omphalos, according to Diodorus 2, is, that when the infant Jupiter was nursed by the Curetes, his navel fell at the river Triton in Crete; whence that territory was called Omphalos. But this legend is evidently invented from the ambiguity of the word. Bryant derives omphalos from OMPHIEL, "the oracle of the sun 3." Such an oracle would not be unaptly represented by a coiled serpent, a serpent being the most popular emblem of the sun, and also of an oracle.

3. The third feature, and the most remarkable of all, in the Bacchic orgies, was the mystic SERPENT. This was, undoubtedly, the σύμβολον μέγα καὶ μυστήριον of the festival. The MYSTERY of religion was, throughout the world, concealed in a chest or box. As the Israelites had their sacred ark, every nation upon earth had some holy receptacle for sacred things and symbols. The story of Ericthonius is illustrative of this remark. He was the fourth king of Athens, and his body terminated in the tails of serpents, instead of human legs. He was placed by Minerva in a basket, which she gave to the daughters of CECROPS, with strict injunctions not to open it. Here we have a fable made out of the simple fact of the mysterious basket, in which the sacred serpent was carried at the orgies of Bacchus. The whole legend relates to Ophiolatreia.

In accordance with the general practice, the worshippers of Bacchus carried in their consecrated baskets or chests, the MYSTERY of their God, together with the offerings.

Catullus, (Nuptiæ Pel. et Thetidis, 256,) in describing these Bacchanals, says:

Pars sese tortis serpentibus incingebant,

Pars obscura cavis celebrabant orgia cistis. p. 194

The contents of the basket were, therefore, the MYSTERY; and especially the serpent. Archbishop Potter says as much: "In these consisted the most mysterious part of the solemnity;" but he adds, inconsiderately, "and therefore to amuse the common people (!) serpents were put into them, which sometimes crawling out of their places, astonished the beholders 1." Whatever might have been the astonishment of the beholders, that of the priests would not have been little, to have been told that their sacred serpent, the of σύμβολον μέγα καὶ μυστήριον, was nothing more than a device to amuse the common people.

It is observable that the Christian Ophites, who were of the school of the Egyptian gnostics, kept their sacred serpent in a chest; and the orgies of Bacchus were derived from the same source of Egyptian gnosticism--the mysteries of Isis.

So great was the veneration of the Cretans for their Bacchic baskets, that they frequently stamped the figures of them upon their coins. Nor were these baskets confined to the orgies of Bacchus. They were employed also in the mysteries of Ceres, Isis, and Osiris 2.

Another custom of the Bacchantes is remarkable for its connexion with Ophiolatreia. After the banquet, they were accustomed to carry round a cup, which they called "the cup of the good dæmon." "Ingenti clamore BONUM DEUM invocant venerantes Bacchum, cujus quoque in memoriam POCULUM, sublatis mensis, circumferunt, quod poculum BONI DÆMONIS appellant 1."

The symbol of the "good dæmon" was a serpent, as may be proved from a medal of the town of Dionysopolis, in Thrace. On one side of the coin were the heads of Gordian and Serapis, on the other a coiled serpent 2. Dionysopolis was named from Dionusus, a name which was borne by the Indian Bacchus, who in his own country was called Deonaush.

In the collection of the Earl of Besborough, was a beautiful antique drinking cup cut out of a solid piece of rock crystal, on the lid of which are two serpents, and upon the cup near the rim, the Ophite hierogram in the form of a Medusa's head. Mr. Pownall, in the seventh volume of the Archæologia, proves that this cup was consecrated to religious uses; and supposes that it might have been employed in drinking to the Tria Numina, after a feast. One of the "Tria Numina" was called AGATHODÆMON. I conjecture therefore, that this was the "poculum Boni Dæmonis," used in the Bacchanalian mysteries.

The following lines from Martial, prove that the impress of a serpent upon a cup, was a sign of consecration:

Cælatus tibi cum sit Ammiane

Serpens in paterâ Myronis arte,

Vaticana bibis!

Lib. vi. Epig. 92. The serpent entered into the symbolical worship of many others of the Grecian deities.

Minerva was sometimes represented with a dragon; her statues by Phidias were decorated with this emblem 1. In plate, p. 85, vol. i. of Montfaucon, are several medals of Minerva; in one of them she holds a caduceus in the right hand; in another, a staff, round which a serpent is twisted; in a third, a large serpent appears marching before her. Other medals represent her crest as composed of a serpent. So that this was a notorious emblem of the goddess of WISDOM: so applied, perhaps, from a legendary memorial of "the subtilty" which the serpent displayed in Paradise; whereas, his attribution to the god of DRUNKENNESS may be accounted for from a traditionary recollection of the prostration of mind sustained by our first parents, through communion with the serpent tempter.

The city of Athens was peculiarly consecrated to the goddess Minerva; and in the Acropolis was kept a live serpent, who was generally considered as the guardian of the place. The emperor Hadrian built a temple at Athens to Jupiter Olympius, and "placed in it a dragon which he caused to be brought from India 1." Upon the walls of Athens was sculptured a Medusa's head, whose hair was intertwined with snakes. In the temple of Minerva, at Tegea, there was a similar sculpture, which was said to have been given by the goddess herself, to preserve that city from being taken in war 2. The virtue supposed to reside in this head was of a talismanic power, to preserve or destroy.

The same author 1 who records the preceding fact, tells us of a priestess, who, going into a sanctuary of Minerva in the dead of the night, saw a vision of that goddess, who held up her mantle, upon which was impressed a Medusa's head. The sight of this fearful talisman instantaneously converted the intruder into stone. The same Gorgon or Medusa's head, was on the aegis and breastplate of the goddess 2, to induce a terrific aspect in the field of battle. The terror resided in the snakes; for the face of Medusa was "mild and beautiful 3." From some such notion of a talismanic power, perhaps, the Argives, Athenians, and Ionians, after the taking of Tanagra from the Lacedæmonians, erected a statue of victory in the grove of Jupiter Olympius, on whose shield was engraved a Medusa's head 4. The same symbolical figure may be frequently seen on sepulchral urns. This general impression of a powerful charm inherent in the Gorgon, must be attributed to some forgotten tradition respecting the serpents in the hair; for all agree that the face of Medusa was far from being terrific. Some engravings of this head, preserved in Montfaucon, explain the mystery. From these we may infer, that this celebrated talisman was no other than the still more celebrated emblem of consecration, the CIRCLE, WINGS, and SERPENT; whose history, use, and probable origin we considered in the first chapter of this treatise. In the plate in Montfaucon, above referred to 1, are representations of Medusa's head, from either side of whose forehead proceeds a WING; and TWO SERPENTS, intersecting one another below the chin in a nodes Herculis, appear over the forehead, looking at each other.

Take away the human face in the centre, with its remaining snaky locks, and you have the Egyptian emblem of consecration, THE SERPENTS AND WINGED CIRCLE; the circle being formed by the bodies of the snakes. The Gorgon is, therefore, nothing more than THE CADUCEUS without its staff.

The intimate connexion of this emblem with the serpent-worship, we have already observed: and it is worthy of remark, that the Argives, Athenians, and Ionians, who erected the statue of victory at Tanagra with a Gorgon-shield, were descendants of serpent worshippers.

This celebrated hierogram of the Ophites was painted on the shield of Perseus, an Argive, who was distinguished by the device of "Medusa's head." And Hippomedon, an Argive also, one of the seven chiefs before Thebes 1, bore the same hierogram, if 1 rightly understand these lines of Æschylus:--

Ὄφεων δὲ πλεκτάναισὶ περίδρομον κύτος

Προσηδάφισται κοιλογάστορος κύκλου.

Ἑπρὰ ἐπὶ Θήβας. 501, 502. [paragraph continues] The poet is describing the devices upon the shields of the besiegers, and the above are the "armorial bearings" of Hippomedon. "The hollow circumference of the concave shield was carried towards the ground (προσηδάφισται) in the folds of serpents." By which I understand the poet to mean, that the centre of the shield was a little raised, and a circular cavity ran round between it and the rim of the shield. In this cavity (towards the lower part of it) were folded serpents--which would accurately describe the ophite hierogram 1; the raised part of the shield representing the mystic circle or globe--for we must observe, that the shield was "hollow-bellied;" i.e. concave to the bearer; and, consequently, convex to the enemy.

The people of Argos had a tradition which indicates their ophite origin also. The city was said to have "been infested with serpents, until Apis came from Egypt and settled in it. To him they attribute the blessing of having their country freed from this evil; but the brood came from the very quarter from whence Apis was supposed to have come. They were certainly Hivites from Egypt 2."

The breastplate and baldrick of Agamemnon, king of Argos, exhibited the device of a triple-headed serpent 3. His brother Menelaus, king of Sparta, was similarly distinguished by a serpent upon his shield. The Spartans, as well as the Athenians, believed in their serpentine origin, and called themselves ophiogenæ.

In Argolis, moreover, was the town of Epidaurus, famous for the temple of Æsculapius, where that god was worshipped under the symbol of a serpent. We read in Pausanias 1 that live serpents were kept here, and fed regularly by servants, who laid their food upon the floor, but dared not approach the sacred reptiles. This must have been only through religious awe; for the serpents of Epidaurus were said to be harmless 2. The statue of Æsculapius at this temple, represented him leaning upon a staff, and resting one hand upon the head of a serpent 3. His sister, the goddess Hygeia, was represented with a large serpent twisted about her, and drinking out of a chalice in her hand. Sometimes it was coiled up in her lap; at others, held in the hand 4.

The serpent was sacred to Æsculapius and Hygeia, as a symbol of health; but how he came to be a symbol of health is not very satisfactorily explained. It is said by Pliny, that the flesh of this creature is sometimes used in medicine, and that this was the reason of his consecration to "health." Others again inform us, that the serpent changes his skin periodically, and thus becomes an emblem of renewed vigour in a sick man. These, however, can only be considered as the surmises of a warm imagination 1. The use of animals of the reptile kind in medicine was not confined to the serpent; or, if it were, from whence could the idea itself originate, that the serpent's flesh was sanatory? The changing of his skin being periodical, can scarcely denote recovered health, which is seldom renewed at given intervals. In the absence of every other probable reason, we may refer this notion to the effect produced upon Adam and Eve, when, at the instigation of THE SERPENT, they "took and ate," and "their eyes were opened." Another derivation has indeed been assigned, which has much plausibility attached to it; but chronology confutes the opinion. Many authors have believed that the erection of the brazen serpent in the wilderness by Moses, might have given cause for the attribution of the serpent to the god of health; especially as he is represented very often, under this character, encircling a stick or pole in the hand of Æsculapius. I acknowledge the affinity of the ideas; but being persuaded that the Æsculapian worship was of Egyptian origin, and having already shown from Wisdom, ch. xi. ver. 15, that the worship of the serpent prevailed in Egypt before the Exodus of the Israelites, I cannot believe that an Egyptian superstition owes its beginning to any incident in Israelitish history.

A tradition is recorded by Pausanias 1 of one Nicagora, the wife of Echetimus, who conveyed the god Æsculapius to Sicyon under the form of a serpent. The Sicyonians erected statues to him; one of which represented a woman sitting upon a serpent. An anecdote of the deportation of Æsculapius to Rome, similar to the preceding, is related by Livy, Ovid, Floras, Valerius Maximus, and Aurelius Victor. From whom it appears, that a pestilence having arisen in Rome, the oracle of Delphi advised an embassy to Epidaurus, to fetch the god Æsculapius; Quintus Ogulnius and ten others were accordingly sent with the humble supplications of the senate and people of Rome. While they were gazing in admiration at the superb statue of the god, a serpent, "venerable, not horrible," which rarely appeared but when he intended to confer some extraordinary benefit, glided from his lurking place; and having passed through the city, went directly to the Roman vessel, and coiled himself up in the berth of Ogulnius. The ambassadors, "carrying the god," set sail; and being off Antium, the serpent leaped into the sea, and swam to the nearest temple of Apollo, and after a few days returned. But when they entered the Tiber, he leaped upon an island, and disappeared. Here the Romans erected a temple to him in the shape of a ship; and the plague was stayed "with wonderful celerity."

Ovid, (Met. 15, 665,) gives an animated description of this embassy, which is well worthy of attention, as illustrative of the deification of the serpent.

Postera sidereos aurora fugaverat ignes;

Incerti quid agant proceres, ad templa petiti

Conveniunt operosa Dei: quaque ipse morari

Sede velit, signis cœlestibus indicet, orant. p. 206

Vix bene desierant cùm cristis aureus altis

In SERPENTE DEUS prænuntia sibila misit:

Adventuque suo signumque arasque foresque

Marmoreumque solum, fastigiaque aurea movit:

Pectoribusque tenus mediâ sublimis in æde

Constitit; atque oculos circumtulit igne micantes.

Territa turba pavet, cognovit NUMINA custos,

Evinctus vittâ trines albente sacerdos.

Et "DEUS en! DEUS en! linguisque animisque favete

Quisquis ades," dixit. "Sis, O pulcherrime, visus

Utiliter: populosque juves TUA SACRA colentes." The god having passed through the temple and city, arrives at the port:

Restitit hic; agmenque suum, turbæque sequentis

Officium placido visus dimittere vultu,

Corpus in Ausoniâ posuit rate. When the vessel entered the Tiber, the whole city of Rome was poured out to meet the god:

Obvia turba ruit -------------

------------ lætoque clamore salutant.

Quaque per adversas navis cita ducitur undas,

Thura super ripas, arisque ex ordine factis,

Parte ab utraque sonant: et adorant aëra fumis,

Ictaque conjectos incalfacit hostia cultros. These spirited lines alone, without any other

support from history, would prove the extent to which the worship of the serpent was carried by the ancients.

The incarnation of deity in a serpent was not an uncommon event in Grecian mythology. We read of Olympias, Nicotelea, and Aristodamia, mothers, of Alexander, Aristomenes, and Aratus, respectively, by some god who had changed himself into the form of a serpent 1. The conversion of Jupiter and Rhea into snakes, gave occasion to a fable respecting the origin of the Caduceus; which is so far pertinent to our theory, that it implies the divine character of those sacred serpents, which formed in that talisman the circle and crescent.

Jupiter again metamorphosed himself into a dragon, to deceive Proserpine. These, and all other similar fables in mythology, are founded upon the deception of Eve by a SPIRITUAL BEING, who assumed the form of a serpent.

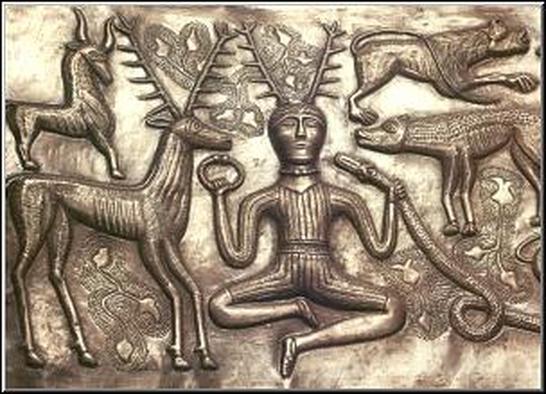

Dragons were sacred to the goddess Ceres; her car was drawn by them.

They were symbolical also of the Ephesian Diana, and of Cybele, the mother of the gods,

as we may see in the engravings of Montfaucon 1.

Of all the places in Greece, Bœotia seems to have been the most favourite residence of the Ophites. The Thebans boasted themselves to be the descendants of the warriors who sprung from the dragon's teeth sown by Cadmus. "The history of this country," says Bryant, "had continual reference to serpents and dragons; they seem to have been the national insigne at least of Thebes. Hence we find upon the tomb of Epaminondas, the figure of a serpent, to signify that he was an Ophite or Theban 2." In like manner the Theban Hercules bore upon his shield the sacred hierogram by which the warriors of the Cadmian family were distinguished--"As he went, his adamantine shield sounded . . . . . . . . in a CIRCLE TWO DRAGONS were suspended, lifting up their heads 3."

At Thespiæ, in Bœotia, they worshipped Jupiter Saotas; the origin of whose worship is thus related: When A DRAGON had once laid waste the town, Jupiter directed that every year a young man, chosen by lot, should be offered to THE SERPENT. The lot fell at length on Cleostrus, when his friend, Menestratus, having made a brazen breastplate and studded it with hooks, put it on, and presented himself to the dragon. Thus they both perished together. From that time the Thespians erected an altar to Jupiter Saotas 1."

But the most celebrated seat of Ophiolatreia in Greece was at DELPHI. The original name of this place, according to Strabo, was PYTHO; supposed to be so called from the serpent PYTHON, slain there by Apollo. The connexion of such a legend with the place, and the derivation of its original name from the serpent Python, which is thought to be the PETHEN of the Hebrews, might well induce the learned Heinsius to conclude that "the god Apollo was first worshipped at Delphi, under the symbol of a serpent." Hyginus 2 says, that the dragon Python formerly gave oracles in Mount Parnassus--"PYTHON, Terræ filius, draco ingens. Hic ante Apollinem ex oraculoresponsa dare solitus erat." The same says

Ælian 1; and Plutarch 2 affirms, that the contest between Apollo and Python was respecting the oracle. Python was, therefore, in reality, the deity of the place 3."

The public assemblies at Delphi were called Pythia. These were doubtless, originally intended for the adoration of Python 4. Seven days after the victory of Apollo over Python, the Pythian games were instituted, on the seventh day of which, an hymn called Paean was sung to Apollo in honour of his victory 5. Hence the expression of Hesiod--ἕβδομον ἱερὸν ἦμαρ--which so singularly corresponds with our Sabbath.

When the priestess of Apollo delivered her oracles, she stood, or sat, upon a tripod. This was a name commonly given to any sort of vessel, seat, or table, supported upon three feet. The tripod of the Pythian priestess was distinguished by a base emblematical of her god. It was a triple-headed serpent of brass, whose body, folded in circles growing wider and wider towards the ground, formed a conical column. The cone, it should be remembered was sacred to the solar deity. The three heads were disposed triangularly, in order to sustain the three feet of the tripod, which was of gold. Herodotus 1 tells us, that it was consecrated to Apollo by the Greeks, out of the spoils of the Persians after the battle of Plata a. He describes it accurately. Pausanias 2, who mentions it also, omits the fact of the three heads. He records a tradition of a more ancient tripod, which was carried off by the Tyrinthian Hercules, but restored by the son of Amphitryon. An engraving of the serpentine column of the Delphic tripod may be seen in Montfaucon, vol. ii. p. 86. The golden portion of this tripod was carried away by the Phocians when they pillaged the temple of Delphi; an outrage which involved them in the sacred war which terminated in their ruin. The Thebans, who were the foremost among the avengers of Delphi, were the most notorious Ophites of antiquity.

Athena us calls this tripod, "the tripod of truth 1,"--a most singular perversion of the fact upon which the oracle was founded--the conversation of the serpent in Paradise.

According to Gibbon, the serpentine column was transported from Delphi to Constantinople, by the founder of the latter city, and set up on a pillar in the Hippodrome 2. He cites Zosimus, who is also cited by Montfaucon on the same subject: but the latter thinks that Constantine only caused a similar column to be made, and did not remove the original from Delphi. It is most probable, however, that Gibbon is right 3.

This celebrated relic of Ophiolatreia is still to be seen in the same place, where it was set up by Constantine; but one of the serpents' heads is mutilated. This was done by Mahomet the second, the Turkish conqueror of Constantinople, when he entered the city. The story is thus related by Leunclavius:--"When Mahomet came to the Atmeidan, he saw there a stone column, on which was placed a three-headed brazen serpent. Looking on it, he asked, 'What idol is that?' and at the same time, hurling his iron mace with great force, knocked off the lower jaw of one of the three serpents' heads. Upon which, immediately, a great number of serpents began to be seen in the city. Whereupon some advised him to leave that serpent alone from henceforth; since through that image it happened that there were no serpents in the city. Wherefore that column remains to this day. And although, in consequence of the lower jaw of the brazen serpent being struck of', some serpents do come into the city, YET they do no harm to any one 1."

This traditionary legend, preserved by Leunclavius, marks the strong hold which Ophiolatreia must have taken upon the minds of the people of Constantinople, so as to cause this story to be handed down to so late an æra as the seventeenth century. Among the Greeks who resorted to Constantinople were many idolaters of the old religion, who would wilfully transmit any legend favourable to their own superstition. Hence, probably, the charm mentioned above, was attached by them to the Delphic serpent on the column in the Hippodrome; and revived (after the partial mutilation of the figure) by their descendants, the common people, who are always the last in, every country to forget or forego an ancient superstition. Among the common people of Constantinople, there were always many more pagans than Christians at heart. With the Christian religion, therefore, which they professed, would be mingled many of the pagan traditions which were attached to the monuments of antiquity that adorned Byzantium, or were imported into Constantinople.

There is another kind of serpentine tripod, which is supposed to have belonged to Delphi, usually represented on medals. This is a vase supported on three brazen legs, round one of which is twined a serpent 1.

Lucian 2 says, that "the dragon under the tripod spoke 3." This was, very probably, the popular belief, founded originally upon the historical fact to which I have so often alluded--the speaking of the serpent in Paradise with a human voice; and the delusion was probably kept up by the ventriloquism of the Pythian priestess, as she sat upon the tripod, over the serpent.

That THE SERPENT was the original god of Delphi, may be further argued from the circumstance that live serpents were kept in the adytum of the temple 1. A story is related by Diogenes Laertius, lib. v. c. 91, of a Pythian priestess, who was accidentally killed by treading upon one of these reptiles, which immediately stung her.

At DELOS, the next place in rank after Del-phi for an oracle of Apollo, there was an image erected to him "in the shape of a dragon 2." Here there was likewise an oracular fountain, called Inopus. "This word," remarks Bryant 3, is compounded of Ain-opus.; i.e. Fons Pythonis:" dedicated to the serpent-god Oph. Fountains sacred to this deity were not uncommon.

Maundrel mentions a place in Palestine, called "the serpent's fountain;" and there was a celebrated stream at Colophon, in Ionia, which communicated prophetic inspiration to the priest of Apollo, who presided over it. Colophon, is col-oph-on; that is, "collis serpentis solis 1."

In Pausanias (lib. ix. 557) we read of a fountain near the river Ismenus at Thebes, which was placed under the guardianship of a dragon. Near this place was the spot where Cadmus slew the dragon, from whose teeth arose the Ophiogenes, the builders of Thebes. It is probable, therefore, that instead of being sacred to Mars, as Pausanias affirms, this fountain was sacred to the serpent-god, called Mars in this place, because of the conflict between the Ophiogenes. A conclusion the more probable from the fact, that the Ismenian hill was dedicated to Apollo. The whole territory was (we may say) the patrimony of Oph--all the local legends confirm it 2.

There were many other oracles of Apollo besides those of Delphi and Delos, but of inferior celebrity and various rites. It is remarkable, however, that the names of several of these places involve the title AUB or AB, the designation of the serpent-god. But not desiring to lay too much stress upon etymology, I pass them by, as I have many other places involving a similar evidence. I cannot, however, neglect a famous oracle which was in connexion with Delphi, and bears many internal marks of Ophiolatreia. This was the celebrated CAVE OF TROPHONIUS, in Phocis.

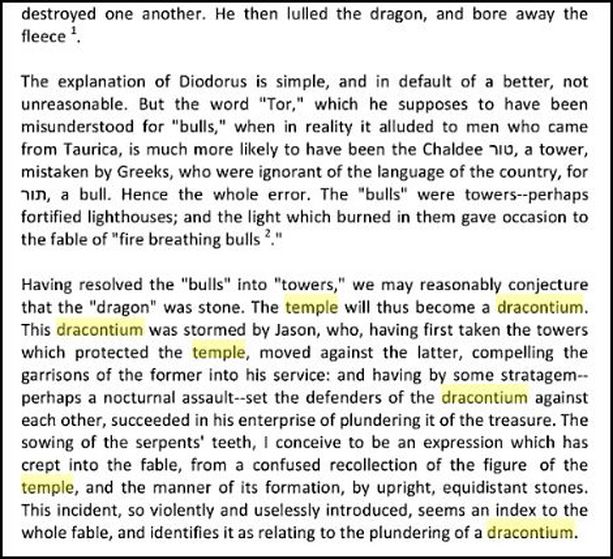

That this was a dracontic oracle will, I think, appear from the following considerations. In the grove of Trophonius, near Lebadea in Phocis, was a cave, in which were two figures, male and female, holding in their hands secptres encircled by serpents. They were said to be the images of Æsculapius and Hygeia; but Pausanias 1the serpent was not more sacred to Æsculapius than to Trophonius." Trophonius was an oracular god, and his attributes and name indicate the solar serpent OPH. TROPHON is,

most probably, TOR-OPH-ON, the temple of the solar serpent 1. The later Greeks, with their usual mythological confusion of places and persons, conjectured the name of the temple to be that of the god; and so converted "Tor-oph-on" into "Trophonius."

In corroboration of these remarks, we find that one of the builders of the temple of Apollo, at Delpi, was Trophonius.

Pausanias informs us, that whoever would inquire an oracle of Trophonius, must previously (in a small temple near his cave, dedicated to THE GOOD GENIUS) sacrifice to APOLLO, SATURN, JUPITER, JUNO, and CERES. Now it is remarkable that each of these deities had some connexion with the mythological serpent. APOLLO was pre-eminently the solar serpent-god; and is, therefore, first to be appeased. Apollo I take to be no other than OPEL, (Oph-el) PYTHO-SOL, whose name occurs so frequently in composition with the names of places as Torophel, Opheltin, &c. SATURN was married to OPS; under which disguise is concealed the deity OPH. JUPITER changed himself into a serpent twice, to deceive Rhea

and Proserpine. The serpent Python was an emissary of JUNO, to persecute Latona, the mother of Apollo; and the car of CERES was drawn by serpents. Serpents also entered into the Eleusinian mysteries as symbolical of that goddess. Thus the history of each of these deities was, more or less, connected with the mythological serpent--the very deity whom the frequenters of this oracle would be called upon to propitiate before they entered the cave, on the supposition that TROPHONIUS was the OPHITE GOD.

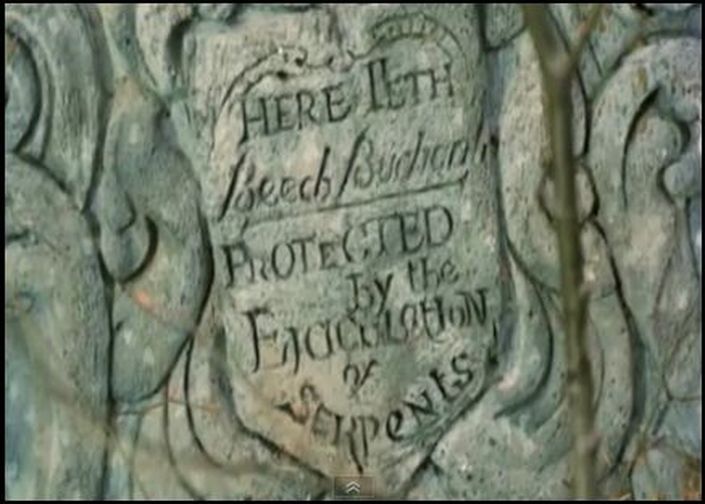

But this is not all. In the cave of Trophonius LIVE SERPENTS were kept; and those who entered it were obliged to appease them by CAKES--which we know were offered to the sacred serpent at Athens, and were carried in the mysterious baskets at the Bacchanalian orgies. They were, in fact, sacrifices or offerings to these serpents, as objects of WORSHIP.--Another proof that the serpents were the real gods of the place, is found in the saying, that "no one ever came out of the cave of Trophonius smiling"--and why? διὰ τὴν τῶν ὄφεων ἔκπληξιν--because of the STUPOR occasioned by the serpents 1! The same expression is employed by Plutarch, in describing the effect produced by the Bacchanalian serpents upon the spectators of the mysteries--ἐξέπληττον τοὺς ἄνδρας 2:--which must mean that they inspired the beholders with religious awe; for it can scarcely mean "frightened," because he is speaking of the processions of Olympias, at Pella, where serpents were so familiar that they lived in the dwellings of the inhabitants, among their children 3, and therefore could, under no ordinary circumstances, become an object of terror. Hence it was, probably, a religious dread which seized the spectators, both at the orgies of Bacchus, and in the cave of Trophonius.

But we may approach even nearer to the deduction which I would draw; namely, that the serpents in the cave were the real gods of the place, by recollecting two fables which we have before considered: the stupefaction and ultimate death of the priest who intruded upon the privacy of the dragon of Metele; and the conversion of the priestess of Minerva into stone, for her presumption in entering into the presence of that goddess uncalled. These fables would prove that an affection of the senses was believed to be the result always attending upon a sight of the local deity.

The serpents were therefore, probably, the original objects of divine worship in the cave of Trophonius.

The origin of the notion of an oracular God symbolized by a serpent, we have frequently referred to the ambiguously prophetic conversation of THE SERPENT with Eve in paradise. The consequent affection and depravation of her mind, and that of her husband, are not obscurely remembered in the ἔκπληξις is of the votaries of Trophonius.

4. The worship of the serpent prevailed equally in the Peloponnesus. Peloponnesus is said to have been so called from being the "island of the Pelopidæ," descendants of PELOPS. The emigration of this mythological hero from Phrygia, forms an interesting epoch in Grecian story, and relates to the passage of the SACRED SERPENT from Canaan, the land of his first resting-place after the flood. PELOPS is P’-EL-OPS, the serpent-god 1.

We have already seen that the Argives and Spartans were Ophites, and that from the celebrated temple of Æsculapius, at Epidaurus, the sacred serpent was conveyed to Sicyon. In addition to these facts, we learn from Pausanias that Antinoe, the foundress of Mantinea, was guided to that place by a serpent, from whom the river, which was near the town, was called Ophis 2.

The first prophet of Messene was said to have been Ophioneus; from which we may infer, that the first colony which introduced religious rites into Messenia was Ophite. A similar colony was established at Epidaurus Limera, in Laconia, under the auspices of a sacred serpent brought from Epidaurus, in Argolis 3.

Statius 4 describes a serpent, the object of religious reverence at Nemæa:--

Interea campis nemoris sacer horror Achæi,

Terrigenæ erigitur serpens------ This is the serpent which slew the child Opheltes. Statius goes on to describe him:

Inachio sanctum dixere tonanti

Agricolæ, cui cura loci et sylvestribus aris

Pauper honos. The "pauper honos" was occasioned by the drought then raging, when the scene described by the poet took place. It was in search of food that the serpent sallied from the sacred grove when he saw and slew the sleeping child.

Bryant 1 assures us that Opheltes, or rather Opheltin, is the name of a place, and not of any person: and that this place was nothing more nor less than an inclosure sacred to the god OPHEL, the serpent-solar deity. Hence the legend respecting the serpent.

It will be shown in a subsequent chapter, that such inclosures were frequently formed in the shape of a serpent. If such was the form of "Opheltin," the fable explains itself. It means nothing more than that human victims were immolated at this shrine of OPHEL.

5. The islands of the Ægean sea were entirely overrun by Ophites. They colonized Delos, Tenos, Cos, and Seriphus, in such numbers as to mark their abode by traditions. The oracle of Delos we have ascertained to have been Dracontian. Tenos was called Ophiusa 1, as also Cythnus. A coin of Cos presents the figure of a serpent, with the word ΣΩΤΗΡ inscribed. The same figure and inscription appear on the coins of Epidaurus 2: and we find that there was a temple of Æsculapius at Cos 3. Seriphus is, according to Bryant, Sar-Iph (petra Pythons,) "the serpent's rock." Here was a legend of Perseus bringing Medusa's head, and turning the inhabitants into stone 4. The island was called Saxum Seriphium by the Romans; and by Virgil, "serpentifera." Natural ruggedness is not peculiar to Seriphus; it seems to be characteristic of the greater number of the Grecian islands; and therefore, connecting the epithet "serpentifera" with the legend respecting Perseus, we may reasonably infer that a colony of Ophites were once settled in Seriphus, and had

a temple there of the dracontic kind, whose upright columns of stone may have given rise to the tradition that the inhabitants of the island were petrified by the talismanic serpents 1 of Perseus. Such a tradition was not unfrequently attached to these Ophite temples. Stonehenge was thus called "Chorea Gigantum;" and a Druids' circle in Cumberland, "Long Meg and her Daughters," from a belief that the giants and the fairies were respectively metamorphosed into stone, in the mazes of a dance.

Of all the islands in the neighbourhood of the' Peloponnesus, Crete was most celebrated for its primitive Ophiolatreia. Here the Egyptians first established those religious rites which were called by the Greeks the mysteries of Dionusus or Bacchus. The Cretan medals were usually impressed with the Bacchic basket, and the sacred serpent creeping in and out. Beger has written a treatise on these coins: the following is a description of three which he has engraved.

1. A Bacchic basket, with the sacred serpent. On the reverse, two serpents with their tails intertwined, on each side of a quiver--for the Cretans were famous archers.

2. The Bacchic basket and serpent. On the reverse a temple between two serpents. In the middle of the temple, a lighted altar.

3. The Cretan Jupiter between two serpents.

The inhabitants of Crete are also said to have worshipped the Pythian Apollo. They had a Pythium; and the inhabitants were called Pythians 1.

6. We see, then, that serpent-worship very generally prevailed through Greece and its dependencies. Memorials of it have been preserved in many coins and medals, and pieces of ancient sculpture; and the only reason why we have not more records of this superstition is, that it was superseded by the fascination of the Polytheistic idolatry, which overwhelmed with a multitude of sculptured gods and goddesses the traditionary remains of the original religion.

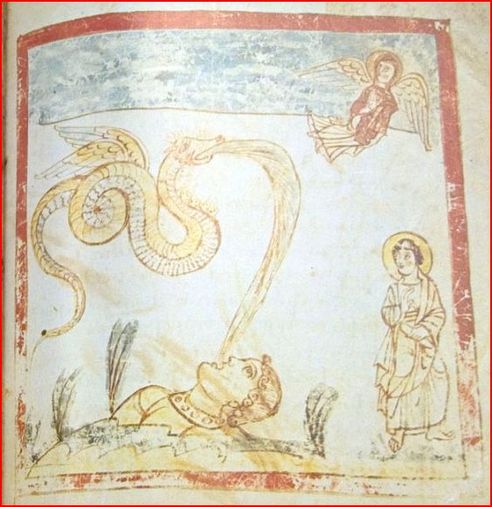

There are, however, some few reliques of sculpture which bear interesting testimony to the worship of the serpent. Engravings of three are preserved by Fabretti 1, which are worthy of attention.

No. 1 represents a TREE encircled by a SERPENT; an altar appears in front, and a boy on horseback is seen approaching it. The inscription states this to be a monument dedicated by Glycon to his infant son Euhemerus.

No. 2, an equestrian approaching an altar at the foot of a TREE, about the branches of which a SERPENT is entwined. A priestess stands by the altar.

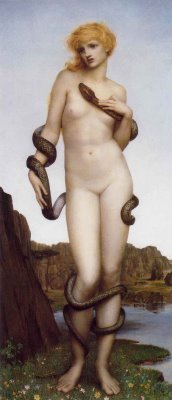

No. 3. In the centre is a TREE with a SERPENT enfolding it. To the right of the tree is a naked female, holding in her hand a chalice under the serpent's mouth, and near her a man in the attitude of supplication to the serpent. On the left is Charon leading Cerberus towards the tree.

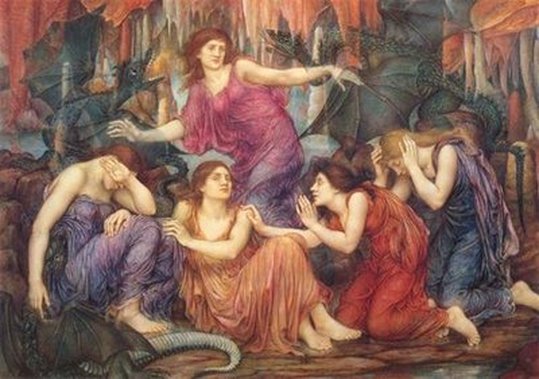

These are perhaps funeral monuments, and the serpent emblematic of the MANES of the departed, as Montfaucon would lead us to believe. But the third sculpture (in spite of Charon) seems rather to allude to the annual custom at Epirus of soliciting the sacred serpent for a good harvest. The narrative is in Ælian, Hist. Anim. lib. xi. 2, by which we learn that the husbandmen of the country proceeded annually to the temple where live serpents were kept, and approached by naked priestesses. If the serpent received the proffered food, the omen was a good one, and vice versâ.

7. Under the head of Ophiolatreia in Greece," we may class Ophiomancy--divination by serpents. This superstition was sometimes resorted to by the Greeks, but was more common among the Romans: both of them borrowed it from earlier nations. For, the same word in Hebrew, Arabic, and Greek, which denotes "divination," denotes "a serpent." "Nachash"--"alahat 1"--οἰωνίζεσθαι--have the same double significations. The Greek word, according to Hesychius, is derived from οἰωνὸς, a snake; "because they divined by means of a snake, which they called οἰωνός."

This is a coincidence which implies that Ophiomancy was the first species of divination: as it ought to have been, since Ophiolatreia was the first species of idolatry.

A remarkable instance of Grecian Ophiomancy occurs in the divination of Calchas at Aulis in

[paragraph continues] Bœotia, before the confederate chiefs sailed for the siege of Troy.

While the chieftains were assembled under a tree, having sacrificed a hecatomb to the gods for the success of their enterprise, on a sudden a great sign--μέγα σῆμα--appeared. A serpent gliding from the base of an altar ascended the tree, and devouring a sparrow and her eight young ones, came down again, and was converted into stone 1. The omen was interpreted to mean a nine years' continuance of the war, and victory in the tenth.

In mentioning this anecdote we may remark, that the scene of the transaction was in Bœotia, one of the most celebrated loci of Ophiolatreia; and that Calchas, the soothsayer, acquired the gift of divination from APOLLO, or in other words, was a priest of the Ophite god.

II. EPIRUS.--l. Following the Ophites from Greece into Epirus, we find that their traces, though few, are decisive. In this country, we are informed by Ælian 2, there was a circular grove of Apollo enclosed within a wall, where sacred serpents were kept. At the great annual

festival, the virgin priestess approached them naked, holding in her hand the consecrated food. If they took it readily, it was deemed an augury of a fruitful harvest, and healthy year; if not, the contrary omen dismissed the anxious expectants in despondence. These serpents were said to be descended from the Python of Delphi,--a tradition which amounts to positive proof that the original religion of Delphi was Ophiolatreia.

2. From Epirus the superstition passed into Illyria. It was at Encheliæ that Cadmus and his wife were changed into serpents. A temple was erected to them in commemoration of this event; the probable form and dedication of which will be considered in the chapter on Ophite Temples.

Cadmus, who was the author of Ophiolatreia in Bœotia, Epirus, and Illyria, from having been the promoter, became the object of this idolatry. Like Thoth in Egypt, he was deified after death as the serpent-god, whose worship he had been so zealous to establish.

3. The superstition so generally received in Greece, passed rapidly into Macedonia, where the inhabitants of Pella became its chief votaries.

Of them 1, it is said that they kept domestic serpents, which were brought up among their children, and frequently nursed together with them, by the Macedonian mothers. The coins of Pella bore the impress of a serpent 2.

The idea of divine incarnation in a serpent must have appeared reasonable in that country to enable Olympias to invent the story of her son Alexander's dracontic origin. The queen was extravagantly fond of the Bacchanalian mysteries, at which she officiated in the character of a Bacchans. It is said by Plutarch 3, that she and her husband were initiated into them at Samothrace, when very young; and that she imitated the frantic gestures of the Edonian women in traversing the wilds of Mount Hæmus. When Olympias celebrated the orgies of Dionusus, attendants followed her, carrying Thyrsi encircled with serpents, having serpents also in their hair and chaplets.

4. The island of Samothrace was the Holy Isle of the ancients, and celebrated for the worship of the CABIRI, the most mysterious and awful of all the gods, whose name, even, it was unlawful to pronounce lightly. The word "cabiri" is said to mean "the mighty ones." If it mean no more we may as vainly seek to penetrate into their hallowed abode for the illustration of our subject as the awe-struck Greeks themselves; but while probability opens a road to conjecture, we may be allowed to hazard one for its elucidation.

"CABIRI" is, evidently a noun in the plural number, of which the singular is to be found in "CABIR."

Now CABIR is probably a compound word, whose component parts may be CA-AB-IR. If so, the interpretation is easy, CA-AB-IR resolving itself at once into CA or CHA, domus 1; AB or AUB, Pythonis; IR or UR, Lucis vel Solis. "CABIR" will therefore mean "the temple of the serpent of the sun 2;" and "CABIRI" will bear the same signification, either as denoting more than one such temple, or a temple dedicated to two deities, AUB and the SUN.

Of the same kind I take to have been the CAABA of Mecca, which should be written CAABIR. Here we find the chief object of idolatry to have been a conical stone, which we know was an emblem of the solar god, being the image of a sun's ray. Another temple of this dedication was at Abury in Wiltshire, whose name, "Abury," is evidently "Abiri," or "Ab-ir," expressed in the plural number; the only difference 1 being, that in the name of this place the adjunct "ca" signifying "the temple," was dropped, and the names of the deity alone retained--ABIR, quasi, "SERPENS SOLIS." This temple we shall see hereafter was formed IN THE SHAPE OF A SERPENT. The substitution of gods for temples was of common occurrence in mythology, as we have seen in the case of Trophonius, where the TOR (or temple) of OPHON was changed into TROPHONIUS (the god.) It is not surprising, therefore, that "caabir," the temple of Abir, should be changed into "Cabir," the god: and by natural consequence, "Cabiri" would imply a plurality of gods of the same name.

The above conjecture, founded primarily upon etymology, is corroborated by FACTS.

Olympias, we have been informed by Plutarch, was initiated into the mysteries of Dionusus at Samothrace. Now Dionusus, the Orphic Bacchus, was symbolized by a serpent. This alone would be sufficient to support our conjecture on the etymology of "Cabiri." But we learn further, that the Orphic CURES, the chief of the CABIRI, assumed a dracontic form; and that the Orphic CRONUS and HERCULES are also described either as compounded of a man, a lion, and a serpent; or, simply, as a winding snake 1. It was a common opinion among the Greeks that Ceres, Proserpine, and Bacchus were the Cabiri. To each of these deities, it is to be observed, the serpent was sacred, and formed a prominent feature in their mysteries.

I leave, therefore, to the candid consideration of the reader, the probability of the derivation which has been assigned to the word "Cabiri."

Between the religion of Samothrace and that of the Thracian continent, there was a strong similarity, or rather union. The great prophet of this common religion was Orpheus, who resided

chiefly at Thrace, and was to that country what Thoth was to Egypt, and Cadmus to Greece,--the promoter of Ophiolatreia: but it was Ophiolatreia in conjunction with the solar idolatry. It seems that the original worship of the serpent had been already corrupted by the adoption of the mysteries of Dionusus. Thus Dionysopolis was "the city of Dionusus;" and consequently we find a coiled serpent impressed upon its coins. The same appeared on the medals of Pantalia, another city in Thrace; upon which Spanheim remarks, "Istud vero ex iis nummis colligas, in Macedoniâ, Thraciâ, Paphlagoniâ, Ponto, Bithyniâ, Ciliciâ, et vicinis regionibus, haud alios locorum genios et custodes gratiores, id genus draconibus extitisse 1."

The priestesses of the superstition of Dionusus were no longer Pythonesses or Oubs, but Bacchantes: and many other innovations mark the decline of Ophiolatreia before Orpheus succeeded (but in succeeding lost his life) in uniting it to the sun-worship.

III. ITALY.--We come now to the traces of Ophiolatreia in Italy.

In this country the principal colony of Ophites settled in Campania, and were called Opici or Ophici, from the object of their idolatry, Ὀφικοὶ ἀπὸ τῶν ὄφεων, say Stephanus Byzantinus 1. The same people were called Pitanatæ, as testified by Strabo 2. "Pitanatæ," remarks Bryant, "is a term of the same import as Opici, and relates to the votaries of Pitan, the serpent-deity, which was adored by the people. Menelaus was, of old, styled Pitanates, as we learn from Hesychius; and the reason of it may be known from his being a Spartan, by which was intimated one of the Serpentigentæ, or Ophites. Hence he was represented with a serpent on his shield 3." This word Pitan is derived from the same root as Python: namely, the Hebrew פתן serpens, vel, aspis.

Many representations of warriors with the serpent on their shields, may be seen on the Etruscan vases, discovered on the estate of Canino in Etruria, which is supposed to have been the ancient Vitulonia 4.

Jerome Colonna attributes the name of Opici to the people of Campania, from a former king

bearing upon his standard the figure of a serpent 1. But this would be the necessary con-sequence of his being an Ophite; for the military ensigns of most ancient nations were usually the images of the gods whom they worshipped. Thus a brigade of infantry among the Greeks was called πιτανάτης 2; and the Romans, in the age of Marcus Aurelius, had a dragon standard at the head of each cohort, ten in every legion. The legion marched under the eagle 3. These dragons were not woven upon any fabric of cloth, but were real images carried on poles 4. Some say (as Casaubon not. in Vopis. Hist. Aug. 231.) that the Romans borrowed the dragon standard from the Parthians: but their vicinity to the Opici of Campania may perhaps suggest a more probable origin. The use of them by the Parthians may have induced the emperor Aurelius to extend them in his own army; but this extension was perhaps rather a revival than an introduction of the dragon ensign. They are mentioned by Claudian in his Epithalamium of Honorius and Maria, v. 193.

Stent bellatrices aquilæ, sævique dracones. He mentions them again in his panegyric on Ruffinus and Honorius. Some of his lines are highly pictorial; such as:

Surgere purpureis undantes anguibus hastas,

Serpentumque vago cœlum sævire volatu.

Ruff. lib. ii. -------------------------hi picta draconum

Colla levant, multusque tumet per nubila serpens,

Iratus, stimulante noto, vivitque receptis

Flatibus, et vario mentitur sibula tractu.

Ibid. Prudentius and Sidonius Apollinaris also mention them.

The bearers of these standards were called draconarii; and it is not improbable that hence might have been derived our own expression of "dragoons," to designate a certain description of cavalry, though the original meaning of the word is altogether lost. This word we have borrowed from the French, who received it probably from the Romans.

From Campania the Ophites passed into Latium,

and established the chief seat of their religion at Lanuvium. The medals of this city bore the figure of a dragon or a large serpent; which, according to Spanheim, would denote that this animal represented the tutelary god of the place: an opinion which is proved correct by the following extracts from Ælian 1 and Propertius. From the former we learn, that at Lanuvium is a large and dark grove, and near it a temple of the Argive Juno. In the same place is a large deep cave, the den of a great serpent. To this grove the virgins of Latium are taken annually to ascertain their chastity, which is indicated by the dragon." Propertius, describing this annual custom speaks thus:

Disce quid Esquilias hac nocte fugavit aquosas,

Cum vicina novis turba cucurrit agris.

Lanuvium annosi vetus est tutela draconis;

Hic ubi tam rarer non perit hora moræ,

Qua sacer abripitur cæco descensus hiatu,

Qua penetral, (virgo, tale iter omne cave!)

Jejuni serpentis honos, cum pabula poscit

Annua, et ex ima sibila torquet humo.

Talia demissæ pallent ad sacra puellæ:

Cum tenera anguino traditur ore manus. p. 240

Ille sibi admotas a virgine corripit escas;

Virginis in palmis ipsa canistra tremunt.

Si fuerint castæ, redeunt in colla parentum,

Clamantque agricolæ "fertilis annus erit 1!"

There is great similarity between the above scene, and that mentioned in a former part of this chapter, as taking place annually in Epirus; and there can be no doubt that they belonged to the same superstition.

The Ophites who settled in Campania and Lanuvium, left a colony also in Crotona, and at Lilybæum in Sicily: for both these places were remarkable for the dracontic medal, which generally denoted the consecration of a city to the serpent-god 2.

The Marsi who settled at the lake Fucinus are said by Virgil, Æn. vii. 750. to have been "charmers of serpents," which is tantamount to calling them Ophites.

Montfaucon 3 has an engraving from a silver medal of Lepidus, on which is a tripod:--"A serpent of vast length raises itself over the vase, twisting his body into a great many folds and

knots . . . . . . . The serpent's head darts rays; which seems to show that this part of the Egyptian Theology (relating to the solar serpent) had spread itself among the Romans; and that they represented the sun by a serpent."

Ophiomancy prevailed among the Romans, when Ophiolatreia had decreased through the influence of time and civilization. The accidental sight of a serpent was sometimes esteemed a good 1, and sometimes a bad omen. The death of Tiberius Gracchus was denoted by a serpent found in his house 2. Sylla was more fortunate in his divination from a serpent which glided from beneath an altar, while he was sacrificing at Nola: as also was Roscius, whose future successful career was foretold, from his being found, when an infant, sleeping in his cradle, enfolded by a snake. In each of these cases Haruspices were sent for, who interpreted the omen.

A serpent was accounted among the pedestria auspicia, and is alluded to by Horace, lib. iii.

ode 27; who seems to consider it a sinister omen:--

Rumpat et serpens iter institutum,

Si per obliquum, similis sagittæ,

Terruit Mannos. Terence 1 also considers it in the same light--

Monstra evenerunt mihi:

Introit in ædes ater alienus canis,

Anguis per impluvium decidit de tegulis. The Sardinians also, as we are informed by De Lacepede, domesticated the serpent, as an animal of auspicious omen. This notion may have reached them either from Italy or Africa.

IV. NORTHERN EUROPE.--The Romans being, comparatively, a modern people, had not among them those strong traces of Ophiolatreia which we have observed in Phœnicia, Egypt, and Greece. But if we now follow the northward march of the sacred serpent from the plains of Shinar, we shall find that he entered deeply into the mythology of the tribes who penetrated into Europe through the Oural mountains. Of these, the Sarmatian horde, as being nearest to the seat of their original habitation, first claims attention.

An unlettered race of wandering barbarians cannot be expected to have preserved many records of their ancient religion; but to the enterprising missionaries of the Christian faith we are indebted for sufficient notices to assure us that THE WORSHIP OF THE SERPENT was their primitive idolatry. To this conclusion we are, indeed, led by the few fragments of tradition in the classical writers who have noticed the religion of the remote Hyperboreans. These people were devoted to the solar superstition 1, of which the most ancient and most general symbol was the serpent. We may therefore expect to find traces of the pure serpent-worship, also, in their religion. They had a priestess called Opis, who came with another priestess (Argis) to Delos, bringing offerings to Lucina, in gratitude for the safe delivery of some distinguished females of their own country 2. These, according to Faber 3, were priestesses of OPH and ARG (the deified personification of the ARK.) Bryant 4 also cites a line from Callimachus,

which gives the name of three priestesses of the Hyperboreans, two of whom are Oupis and Evaion. The latter word he decomposes into eva-on, serpens sol. So that they were representatives of the two superstitions--the simple and primitive serpent-worship, and the worship of the solar serpent. Other obscure, though not altogether uncertain, notices are to be found in Diodorus Siculus, Hecateus, &c. which lead to the conclusion that the Ophite religion was once prevalent in the north of Europe 2. These inferences are corroborated by indisputable facts of modern discovery, which I now proceed to detail.

1. SARMATIA. From Ouzel 1 we learn that the serpent was one of the earliest objects of worship in Sarmatia. He cites Erasmus Stella de Antiq. Borussiæ. "For some time," says this author, "they had no sacred rites; at length they arrived at such a pitch of wickedness, that they worshipped serpents and trees." The connexion between serpents and trees we have had occasion to notice more than once. They

are united on the sepulchral monuments of the Greeks and Romans, on the coins of Tyre, and among the Fetiches of Whidah. We shall find them, in the same union, pervading the religion of the Hyperboreans of every description, the superstition of the Scandinavians, and the worship of the Druids. They are closely connected in the mythology of the Heathens of almost every nation: and the question is not unnatural--"whence arose this union?" The coincidences are too remarkable to be unmeaning; and I have no hesitation in affirming my belief that THE PARADISIACAL SERPENT, and THE TREE OF KNOWLEDGE, are the prototypes of the idolatry.

The Samogitæ (Muscovites) partook of the same superstition 1. They worshipped the serpent as A GOD; and if any adversity befell them, concluded that their domestic serpents (which, like the people of Pella, they kept in their houses,) had been negligently served.

From Muscovy we may follow the same superstition into Lithuania, the modern Poland. These people, we are informed by Guaguin 2,[ "believed vipers and serpents to be gods, and worshipped them with great veneration. Every householder, whether citizen, husbandman, or noble, kept a serpent in his house, as a house-hold god: and it was deemed so deadly an offence to injure or dishonour these serpents, that they either deprived of property or of life every one who was guilty of such a crime."

In Koch (De cultu Serpentum, p. 39: a valuable, though short and superficial treatise,) we read the following passage: That these wretched idolaters offered sacrifices to serpents, Jerome of Prague (teste Sylvio de Europâ, c. 26.) saw with his own eyes . . . . . . Every householder had a snake in a corner of his house, to which he gave food and offered sacrifice, as he lay upon the hay. Jerome commanded all these to be killed, and publicly burnt. Among such as were brought out for this purpose, one was found larger than the rest, which, though often thrown into the fire, could not be consumed."

The serpent-worship of the Lithuanians is also noticed by Cromer 1 who charges the Prussians likewise with the same idolatry. Guaguin relates an anecdote of a serpent worshipper of Lithuania, who was persuaded to destroy his domestic god; and subsequently losing all his bees, (by whose labour he subsisted,) attributed the calamity to his apostacy, and relapsed into his former superstition. The scene of this anecdote was a village near Troki, six miles from Vilna; upon which Masius 1 remarks, "Est quatuor a Vilna miliaribus, Lavariski, villa regia; in quâ a multis ADHUC serpentes coluntur."

The Lithuanians were the last of the Europeans who were converted to Christianity; an event which did not take place until the fourteenth century. Jagello, the last heathen duke, was baptized anno 1386 2.

The inhabitants of Livonia were also addicted to this idolatry, and carried it to a barbarous length. It is said that they were accustomed to sacrifice the most beautiful of their captives to their dragon-gods 3. The same custom we have observed to exist at Whidah.

I. GREECE.--Whether the learned and ingenious Bryant 1 be correct or not, in deriving the very name of EUROPE from אור־אב (AUR-AB), the solar serpent, it is certain that Ophiolatreia prevailed in this quarter of the globe at the earliest period of idolatry 2.

Of the countries of Europe, Greece was first colonized by Ophites, but at separate times, both from Egypt and Phœnicia; and it is a question of some doubt, though perhaps of little importance, whether the leader of the first colony, the celebrated Cadmus, was a Phœnician or an Egyptian. Bochart has shown that Cadmus

p. 184

was the leader of the Canaanites who fled before the arms of the victorious Joshua; and Bryant has proved that he was an Egyptian, identical with THOTH. But as mere names of individuals are of no importance, when all agree that the same superstition existed contemporaneously in the two countries, and since Thoth is declared by Sanchoniathon to have been the father of the Phœnician as well as Egyptian Ophiolatreia; we may endeavour, without presumption, to reconcile the opinions of these learned authors, by assuming each to be right in his own line of argument; and by generalizing the name CADMUS, instead of appropriating it to individuals. By the word CADMUS, therefore, we may understand the leader of the CADMONITES, whether of Egypt or Phœnicia. There would, consequently, be as many persons of this name, as colonies of this denomination.

The first appearance of these idolaters in Europe is mythologically described under the fable of "Cadmus and Europa;" according to which, the former came in search of the latter, who was his sister, and had been carried off to Europe by Jupiter in the form of a bull.

If EUROPA be but a personification of the

p. 185

[paragraph continues] SOLAR SERPENT-WORSHIP, and CADMUS a leader of serpent-worshippers, the whole fable is easily solved.

Europa was carried by Jupiter to Crete, where she afterwards married ASTERIUS: that is, the SOLAR SERPENT-WORSHIP was established in Crete, and afterwards united with the worship of the HEAVENLY HOST: Asterius being derived from ἀστὴρ, a star.

For the explanation of that portion of the fable which relates to the BULL, the reader is referred to Bryant, Anal. vol. ii. 455, who thinks that it bore an allusion to the god APIS of Egypt, by whose oracular advice the migration was undertaken. A similar worship, however, prevailed in Syria; for we find that the Phœnician Cadmus, (Cadmus the son of Phœnix), when he went in search of his sister, followed a cow. This latter colony is said to have settled in Eubœa; to which they gave the name of their tutelary deity, AUB; for Eubœa is, according to Bryant, AUB-AIA, "the land of AUB 1."

The history of Cadmus is full of fables about serpents. He slew a dragon, planted its teeth, and hence arose armed men, who destroyed each other until five only remained. These assisted him in building the city of THEBES. One of these five builders of Thebes was named after the serpent-god of the Phœnicians, OPHION.

Cadmus, and his wife Harmonia, finished their travels at Encheliæ in Illyricum, where, instead of dying a natural death, they were changed into serpents. This conclusion of the story throws a light upon the whole. The leader of these Opiates after death was deified, and adored under the symbol of a serpent. He became, in fact, the SERPENT-GOD of the country, as Thoth had become the serpent-god of Egypt. Having been the author, he became the object of the idolatry.

Besides the Cadmian colony, which settled chiefly in Bœotia, a second irruption of Ophites is noticed in history, as coming from Egypt under the guidance of CECROPS. These took possession of Attica, and founded Athens, whose first name was, in consequence, CECROPIA. In this word, also, we trace the involution of the name OB, or OPS, the serpent-god of antiquity; and accordingly, Cecrops 1 himself is said to have been of twofold form, human and serpentine 1. It was also said, that from a serpent he was changed into a man 2. We read too of DRACO (Δράκων, a dragon) being the first king of Athens. All these relate to the introduction of serpent-worship from Egypt into Attica, the leader of which colony, by a fabulous metonyme, was called a "dragon," or serpent. The first altar erected by Cecrops at Athens, was to OPS, the serpent-deity 3; a circumstance which confirms the inference deduced by Bryant; namely, that he introduced Ophiolatreia into Attica. Cecrops and Draco were probably the same person.