Vinca

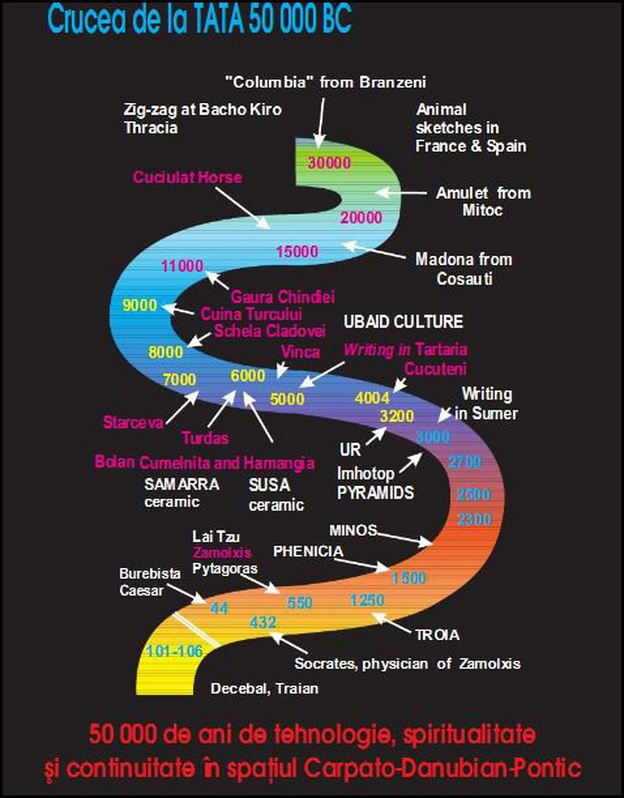

Pre-Sumerian Carpathians

Old Europe

Before Sumer, Crete or the Maltese civilisation, there was “Old Europe”, or the Vinca culture… a forgotten, rather than lost civilisation that lies at the true origin of most of our ancient civilisations.

Philip Coppens

http://www.philipcoppens.com/oldeurope.html

There are lost civilisations, and then there are forgotten civilisations. From the 6th to the 3rd millennium BC, the so-called “Vinca culture” stretched for hundreds of miles along the river Danube, in what is now Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria and the Republic of Macedonia, with traces all around the Balkans, parts of Central Europe and Asia Minor, and even Western Europe.

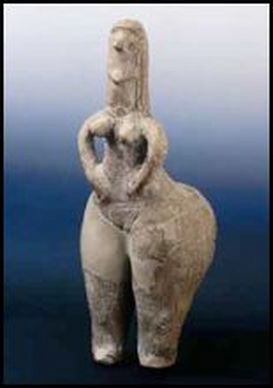

Few, if any, have heard of this culture, though they have seen some of their artefacts. They are the infamous statues found in Sumer, where authors such as Zecharia Sitchin have labelled them as “extra-terrestrial”, seeing that the shapes of these beings can hardly be classified as typically human. So why was it that few have seen (or were aware of) their true origin?

The person largely responsible for the isolation of the Vinca culture was the great authority on late prehistoric Europe, Vere Gordon Childe (1892-1957). He was a synthesiser of various archaeological discoveries and tried to create an all-encompassing framework, creating such terms as "Neolithic Revolution" and "Urban Revolution". In his synthesis, he perceived the Vinca culture as an outlying cultural entity influenced by more “civilised” forces. His dogmatic stance and clout meant that the Vinca culture received only scant attention. Originally, interest in the signs found on pottery had created interest in some academic circles, but that now faded following Childe’s “papal bull”.

Interest was rekindled in the 1960s (following the death of Childe), largely due to a new discovery made in 1961 by Dr. N. Vlassa, while excavating the Transylvanian site of Tartaria, part of Vinca culture. Amongst various artefacts recovered were three clay tablets, which he had analysed with the then newly introduced radiocarbon dating methodology. The artefacts came back as ca. 4000 BC and were used by the new methodology’s detractors to argue that radio carbon-dating was obviously erroneous. How could it be “that” old?

Traditionally, the Sumerian site of Uruk had been dated to 3500-3200 BC. Vlassa’s discovery was initially (before the carbon dating results) further confirmation that the “Vinca Culture” had strong parallels with Sumer. Everyone agreed that the Sumerians had influenced Vinca Culture (and the site of Tartaria), which had therefore been assigned a date of 2900-2600 BC (by the traditional, comparative methodology, which relied on archaeologists’ logic, rather than hard scientific evidence). Sinclair Hood suggested that Sumerian prospectors had been drawn by the gold-bearing deposits in the Transylvanian region, resulting in these off-shoot cultures.

But if the carbon dating results were correct, then Tartaria was 4000 BC, which meant that the Vinca Culture was older than Sumer, or Sumer was at least a millennium older than what archaeologists had so far assumed. Either way, archaeology would be in a complete state of disarray and either some or all archaeologists would be wrong. Voila, the reason as to why radio carbon dating was attacked, rather than merely revising erroneous timelines and opinions.

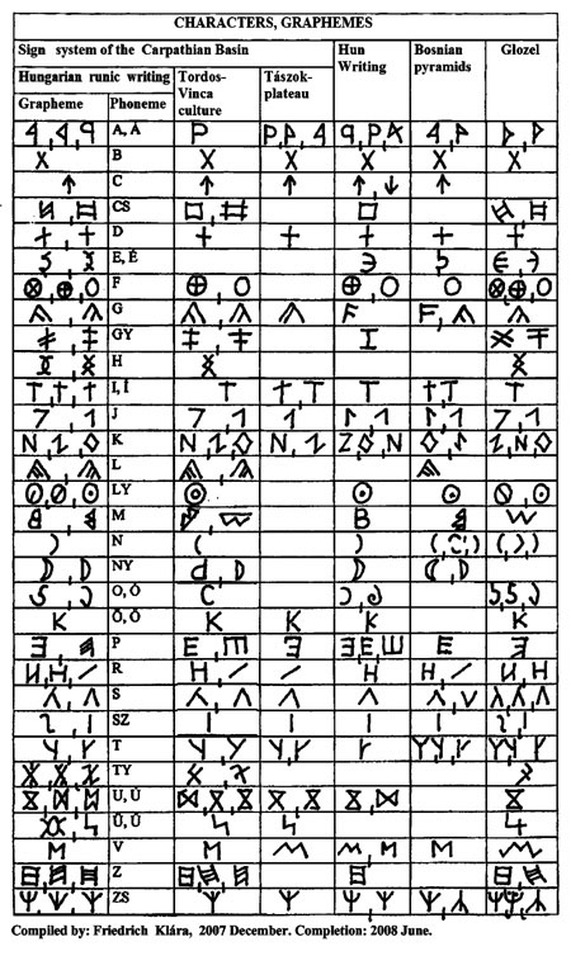

There is no debate about it: the artefacts from the Vinca culture and Sumer are very much alike. And it is just not some pottery and artefacts: they share a script that seems highly identical too. In fact, the little interest that had been shown in the Vinca culture before the 1960s all revolved around their script. Vlassa’s discovery only seemed to confirm this conclusion, as he too immediately stated that the writing had to be influenced by the Near East. Everyone, including Sinclair Hood and Adam Falkenstein, agreed that the two scripts were related and Hood also saw a link with Crete. Finally, the Hungarian scholar Janos Makkay stated that the “Mesopotamian origin [of the Tartaria pictographs] is beyond doubt.” It seemed done and dusted.

But when the Vinca Culture suddenly predated Sumer, this thesis could no longer be maintained (as it would break the archaeological framework, largely put in place by Childe and his peers), and thus, today, the status is that both scripts developed independently. Of course, we should wonder whether this is just another attempt to save reputations and whether in the following decades, the stance will finally be reversed, which would mean that the Vinca Culture is actually at the origin of the Sumerian civilisation… a suggestion we will return to shortly.

But what is the Vinca Culture? In 1908, the largest prehistoric and most comprehensively excavated Neolithic settlement in Europe was discovered in the village of Vinca, just 14 km downstream from the Serbian capital Belgrade, on the shores of the Danube. The discovery was made by a team led by Miloje M. Vasic, the first schooled archaeologist in Serbia.

Vinca was excavated between 1918 and 1934 and was revealed as a civilisation in its own right: a forgotten civilisation, which Marija Gimbutas would later call “Old Europe”. Indeed, as early as the 6th millennium BC, three millennia before Dynastic Egypt, the Vinca culture was already a genuine civilisation. Yes, it was a civilisation: a typical town consisted of houses with complex architectural layouts and several rooms, built of wood that was covered in mud. The houses sat along streets, thus making Vinca the first urban settlement in Europe, but equally being older than the cities of Mesopotamia and Egypt. And the town of Vinca itself was just one of several metropolises, with others at Divostin, Potporanj, Selevac, Plocnik and Predionica. Maria Gimbutas concluded that “in the 5th and early 4th millennia BC, just before its demise in east-central Europe, Old Europeans had towns with a considerable concentration of population, temples several stories high, a sacred script, spacious houses of four or five rooms, professional ceramicists, weavers, copper and gold metallurgists, and other artisans producing a range of sophisticated goods. A flourishing network of trade routes existed that circulated items such as obsidian, shells, marble, copper, and salt over hundreds of kilometres.”

Everything about “Old Europe” is indeed older than anything else in Europe or the Near East. To return to their script. Gimbutas had a go at trying to translate it and called it the “language of the goddess”. She based her work on that of Shan Winn, who had completed the largest catalogue of Vinca signs to date. He narrowed the number of signs down to 210, stating that most of the signs were composed of straight lines and were rectilinear in shape. Only a minority had curved lines, which was perhaps due to the difficulty of curved carving on the clay surface. In a final synthesis, he concluded that all Vinca signs were found to be constructed out of five core signs:

- a straight line;

- two lines that intersect at the centre;

- two lines that intersect at one end;

- a dot;

- a curved line.

Winn however did not consider this script to be writing, as even the most complex examples were not “texts”; he thus labelled them “pre-writing”, though Gimbutas would later claim they were indeed “writing”. Still, everyone is in agreement that the culture did not have texts as that which was written was too short in length to be a story, or an account of a historical event. So what was it?

In Sumer, the development of writing has been pinned down as a result from economical factors that required “record keeping”. For the Vinca Culture, the origin of the signs is accepted as having been derived from religious rather than material concerns. In short, the longest groups of signs are thus considered to be a kind of magical formulae.

The Vinca Culture was also millennia ahead of the status quo on mining. At the time, mining was thought not to predate 4000 BC, though in recent years, examples of as far back as 70,000 years ago have been discovered. The copper mine at Rudna Glava, 140 km east of Belgrade, is at least 7000 years old and had vertical shafts going as deep as twenty metres and at the time of its discovery was again extremely controversial.

Further insights into “Old Europe” came about in November 2007, when it was announced that excavations at an ancient settlement in southern Serbia had revealed the presence of a furnace, used for melting metal. The furnace had tools in it: a copper chisel and a two-headed hammer and axe. Most importantly, several of the metal objects that were made here, were recovered from the site.

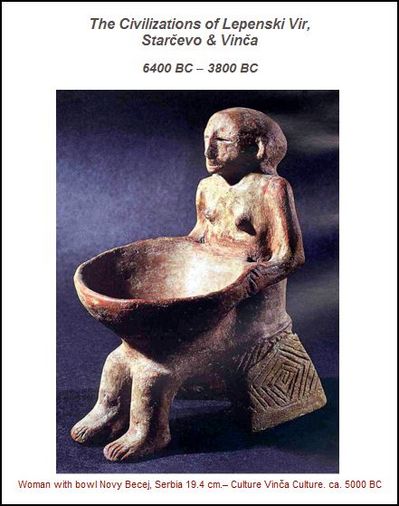

The excavation also uncovered a series of statues. Archaeologist Julka Kuzmanovic-Cvetkovic observed that "according to the figurines we found, young women were beautifully dressed, like today's girls in short tops and mini skirts, and wore bracelets around their arms."

The unnamed tribe who lived between 5400 and 4700 BC in the 120-hectare site at what is now Plocnik knew about trade, handcrafts, art and metallurgy. The excavation also provided further insights into Old Europe: for example, near the settlement, a thermal well might be evidence of Europe’s oldest spa. Houses had stoves and there were special holes for trash, while the dead were buried in a tidy necropolis. People slept on woollen mats and fur, made clothes of wool, flax and leather, and kept animals. The community was also especially fond of children: artefacts that were recovered included toys such as animals and rattles of clay, and small, clumsily crafted pots apparently made by children at playtime.

It is but two examples that underline that Old Europe was a civilisation millennia ahead of its neighbours. And Old Europe is a forgotten culture, as Richard Rudgeley has argued: “Old Europe was the precursor of many later cultural developments and […] the ancestral civilisation, rather than being lost beneath the waves through some cataclysmic geological event, was lost beneath the waves of invading tribes from the east.” Indeed, Rudgeley argued that when confronted with the “sudden arrival” of civilisation in Sumer or elsewhere, we should not look towards extra-terrestrial civilisation, nor Atlantis, but instead to “Old Europe”, a civilisation which the world seems intent on disregarding… and we can only wonder why.

“Civilisation” in Sumer was defined as the cultivation of crops and domestication of animals, with humans living a largely sedentary life, mostly in village or towns, with a type of central authority. With that definition of civilisation, it is clear that it did not begin in Sumer, but in Old Europe. Old Europe was a Neolithic civilisation, living of agriculture and the breeding of domestic animals. The most frequent domestic animals were cattle, although smaller goats, sheep and pigs were also bred. They also cultivated the most fertile prehistoric grain species. There was even a merchant economy: a surplus of products led to the development of trade with neighbouring regions, which supplied salt, obsidian or ornamental shells.

In fact, they were not actually a “Neolithic civilisation” – they were even further ahead of the times: in the region of Eastern Serbia, at Bele Vode and (the already discussed) Rudna Glava, in crevices and natural caves, the settlers of Vinca came in contact with copper ore which they began fashioning with fire, initially only for ornamental objects (beads and bracelets). They were more “Bronze Age” than “Stone Age”… this at a time when the rest of Europe and the Near East was not even a “Stone Age civilisation”.

One scholar, the already cited Marija Gimbutas, has highlighted the importance of Old Europe. So much so, that many consider her to have gone too far. She interpreted Old Europe as a civilisation of the Goddess, a concept which has taken on a life of its own in the modern New Age industry, extending far beyond anything Gimbutas herself could ever have imagined. Bernard Wailes stated how Gimbutas was "immensely knowledgeable but not very good in critical analysis... She amasses all the data and then leaps to conclusions without any intervening argument... Most of us tend to say, oh my God, here goes Marija again". But everyone agrees that her groundwork is solid, and it is from that which we build.

Gimbutas dated the civilisation of Old Europe from 6500 to 3500-3200 BC. It was at that time that the area was overrun by invading Indo-Europeans. The local population could do two things: remain and be ruled by new masters, or migrate, in search of new lands. It appears that the people of Old Europe did both: some went in search of a haven to the south, on the shores of the Aegean Sea, and beyond. Harald Haarmann has identified them as being responsible for the rise of the so-called Cycladic culture, as well as Crete, where the new settlers arrived around 3200 BC.

For Gimbutas, the difference between Old Europe and Indo-Europe was more than just one people invading another. It was the difference between a goddess-centred and matriarchal and the Bronze Age Indo-European patriarchal cultural elements. According to her interpretations, Old Europe was peaceful, they honoured homosexuals and they espoused economic equality. The Indo-Europeans were warmongering males. And it’s that conclusion with which many have great difficulty, for nothing is ever as distinct as that.

Today, artefacts of the Vinca culture grace the display cabinets of several museums, for they are magnificent ceramics – of an artistic and technological level which would not be equalled by other cultures for several millennia. It is believed that their writing originated out of sacred writing. Like Crete, they were a peaceful nation; Crete’s palaces had no defensive qualities.

The recovered artefacts of the Vinca culture equally show they had a profound spiritual life. The cult objects include figurines, sacrificial dishes, anthropomorphic and zoomorphic dishes. When we note that their number (over 1000 examples at Vinca alone) exceeds the total number of figurines discovered in the region of the Greek Aegean, we can only wonder why Old Europe is not better known today.

Life was represented on these objects as embodying the cycle of birth and death of Nature, along with the desire of man to get Nature's sympathy or to mollify it in the interest of survival. Shrines were discovered in Transylvania with complex architectural designs, indicating the involvedness of the rituals which were conducted in them. It may not have been a matriarchal, Goddess worshipping civilisation, but it was definitely a complex and established religious framework. Though nothing suggests it was a Goddess cult.

The same mistake has been made in Malta, where for generations certain statues were interpreted as “Mother Goddess” statues, whereas alternative thinkers as Joseph Ellul pointed out that there was nothing specifically feminine about these statues; that they showed a deity, but that it could equally be male or female. Recently, Ellul’s point of view has become shared by other experts on Malta, such as Dr. Caroline Malone, who argued that the theory that the Maltese temples were erected as part of a goddess-worshipping culture is no longer valid. In her opinion, Maltese prehistoric society was a relatively stable, agricultural community, living on an intense and densely populated island, which celebrated cyclical cycles of life, rites of passage, transitions between different stages of life, from separation to reintegration, fertility, ancestors, all of this within a cosmological context… and very much like Old Europe.

Around 3200 BC, the culture of Old Europe migrated, to the Aegean Sea and to Crete. Today, they are considered to be the origin of the Minoan civilisation, though it is a dimension that few Minoan scholars have included in their writing, instead largely opting to see Crete as yet another “stand alone” civilisation. Gimbutas stated that: “the civilisation that flourished in Old Europe between 6500 and 3500 BC and in Crete until 1450 BC enjoyed a long period of uninterrupted peaceful living.” Motifs such as the snake, intertwined with the bird goddess motif, the bee and the butterfly, with the distinctive motif of the double axe, are found both in Old Europe and Crete. But the best evidence is in the writing of Old Europe and the Linear A script of Crete, which are to all intents and purposes identical.

But it is equally clear that contacts between Sumer and Old Europe existed at the time of the Ubaid culture, in Eridu – the site which inspired Sitchin so greatly in his formulation of the Annunaki theory and his identification of these statues as “Nephilim”. The Ubaid culture is ca. 4500 BC and though we should perhaps not go as far as concluding that Sumer was a child of Old Europe, the two cultures obviously knew each other. Indeed, in recent years, Old European artefacts were even discovered in Southeastern France, suggesting that the civilisation of Old Europe travelled not merely to the East, but also to the West. Perhaps we should even consider them to be at the origin of the megalithic civilisation? But no-one, it seems, has dared to topple that stone yet.

Philip Coppens

http://www.philipcoppens.com/oldeurope.html

There are lost civilisations, and then there are forgotten civilisations. From the 6th to the 3rd millennium BC, the so-called “Vinca culture” stretched for hundreds of miles along the river Danube, in what is now Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria and the Republic of Macedonia, with traces all around the Balkans, parts of Central Europe and Asia Minor, and even Western Europe.

Few, if any, have heard of this culture, though they have seen some of their artefacts. They are the infamous statues found in Sumer, where authors such as Zecharia Sitchin have labelled them as “extra-terrestrial”, seeing that the shapes of these beings can hardly be classified as typically human. So why was it that few have seen (or were aware of) their true origin?

The person largely responsible for the isolation of the Vinca culture was the great authority on late prehistoric Europe, Vere Gordon Childe (1892-1957). He was a synthesiser of various archaeological discoveries and tried to create an all-encompassing framework, creating such terms as "Neolithic Revolution" and "Urban Revolution". In his synthesis, he perceived the Vinca culture as an outlying cultural entity influenced by more “civilised” forces. His dogmatic stance and clout meant that the Vinca culture received only scant attention. Originally, interest in the signs found on pottery had created interest in some academic circles, but that now faded following Childe’s “papal bull”.

Interest was rekindled in the 1960s (following the death of Childe), largely due to a new discovery made in 1961 by Dr. N. Vlassa, while excavating the Transylvanian site of Tartaria, part of Vinca culture. Amongst various artefacts recovered were three clay tablets, which he had analysed with the then newly introduced radiocarbon dating methodology. The artefacts came back as ca. 4000 BC and were used by the new methodology’s detractors to argue that radio carbon-dating was obviously erroneous. How could it be “that” old?

Traditionally, the Sumerian site of Uruk had been dated to 3500-3200 BC. Vlassa’s discovery was initially (before the carbon dating results) further confirmation that the “Vinca Culture” had strong parallels with Sumer. Everyone agreed that the Sumerians had influenced Vinca Culture (and the site of Tartaria), which had therefore been assigned a date of 2900-2600 BC (by the traditional, comparative methodology, which relied on archaeologists’ logic, rather than hard scientific evidence). Sinclair Hood suggested that Sumerian prospectors had been drawn by the gold-bearing deposits in the Transylvanian region, resulting in these off-shoot cultures.

But if the carbon dating results were correct, then Tartaria was 4000 BC, which meant that the Vinca Culture was older than Sumer, or Sumer was at least a millennium older than what archaeologists had so far assumed. Either way, archaeology would be in a complete state of disarray and either some or all archaeologists would be wrong. Voila, the reason as to why radio carbon dating was attacked, rather than merely revising erroneous timelines and opinions.

There is no debate about it: the artefacts from the Vinca culture and Sumer are very much alike. And it is just not some pottery and artefacts: they share a script that seems highly identical too. In fact, the little interest that had been shown in the Vinca culture before the 1960s all revolved around their script. Vlassa’s discovery only seemed to confirm this conclusion, as he too immediately stated that the writing had to be influenced by the Near East. Everyone, including Sinclair Hood and Adam Falkenstein, agreed that the two scripts were related and Hood also saw a link with Crete. Finally, the Hungarian scholar Janos Makkay stated that the “Mesopotamian origin [of the Tartaria pictographs] is beyond doubt.” It seemed done and dusted.

But when the Vinca Culture suddenly predated Sumer, this thesis could no longer be maintained (as it would break the archaeological framework, largely put in place by Childe and his peers), and thus, today, the status is that both scripts developed independently. Of course, we should wonder whether this is just another attempt to save reputations and whether in the following decades, the stance will finally be reversed, which would mean that the Vinca Culture is actually at the origin of the Sumerian civilisation… a suggestion we will return to shortly.

But what is the Vinca Culture? In 1908, the largest prehistoric and most comprehensively excavated Neolithic settlement in Europe was discovered in the village of Vinca, just 14 km downstream from the Serbian capital Belgrade, on the shores of the Danube. The discovery was made by a team led by Miloje M. Vasic, the first schooled archaeologist in Serbia.

Vinca was excavated between 1918 and 1934 and was revealed as a civilisation in its own right: a forgotten civilisation, which Marija Gimbutas would later call “Old Europe”. Indeed, as early as the 6th millennium BC, three millennia before Dynastic Egypt, the Vinca culture was already a genuine civilisation. Yes, it was a civilisation: a typical town consisted of houses with complex architectural layouts and several rooms, built of wood that was covered in mud. The houses sat along streets, thus making Vinca the first urban settlement in Europe, but equally being older than the cities of Mesopotamia and Egypt. And the town of Vinca itself was just one of several metropolises, with others at Divostin, Potporanj, Selevac, Plocnik and Predionica. Maria Gimbutas concluded that “in the 5th and early 4th millennia BC, just before its demise in east-central Europe, Old Europeans had towns with a considerable concentration of population, temples several stories high, a sacred script, spacious houses of four or five rooms, professional ceramicists, weavers, copper and gold metallurgists, and other artisans producing a range of sophisticated goods. A flourishing network of trade routes existed that circulated items such as obsidian, shells, marble, copper, and salt over hundreds of kilometres.”

Everything about “Old Europe” is indeed older than anything else in Europe or the Near East. To return to their script. Gimbutas had a go at trying to translate it and called it the “language of the goddess”. She based her work on that of Shan Winn, who had completed the largest catalogue of Vinca signs to date. He narrowed the number of signs down to 210, stating that most of the signs were composed of straight lines and were rectilinear in shape. Only a minority had curved lines, which was perhaps due to the difficulty of curved carving on the clay surface. In a final synthesis, he concluded that all Vinca signs were found to be constructed out of five core signs:

- a straight line;

- two lines that intersect at the centre;

- two lines that intersect at one end;

- a dot;

- a curved line.

Winn however did not consider this script to be writing, as even the most complex examples were not “texts”; he thus labelled them “pre-writing”, though Gimbutas would later claim they were indeed “writing”. Still, everyone is in agreement that the culture did not have texts as that which was written was too short in length to be a story, or an account of a historical event. So what was it?

In Sumer, the development of writing has been pinned down as a result from economical factors that required “record keeping”. For the Vinca Culture, the origin of the signs is accepted as having been derived from religious rather than material concerns. In short, the longest groups of signs are thus considered to be a kind of magical formulae.

The Vinca Culture was also millennia ahead of the status quo on mining. At the time, mining was thought not to predate 4000 BC, though in recent years, examples of as far back as 70,000 years ago have been discovered. The copper mine at Rudna Glava, 140 km east of Belgrade, is at least 7000 years old and had vertical shafts going as deep as twenty metres and at the time of its discovery was again extremely controversial.

Further insights into “Old Europe” came about in November 2007, when it was announced that excavations at an ancient settlement in southern Serbia had revealed the presence of a furnace, used for melting metal. The furnace had tools in it: a copper chisel and a two-headed hammer and axe. Most importantly, several of the metal objects that were made here, were recovered from the site.

The excavation also uncovered a series of statues. Archaeologist Julka Kuzmanovic-Cvetkovic observed that "according to the figurines we found, young women were beautifully dressed, like today's girls in short tops and mini skirts, and wore bracelets around their arms."

The unnamed tribe who lived between 5400 and 4700 BC in the 120-hectare site at what is now Plocnik knew about trade, handcrafts, art and metallurgy. The excavation also provided further insights into Old Europe: for example, near the settlement, a thermal well might be evidence of Europe’s oldest spa. Houses had stoves and there were special holes for trash, while the dead were buried in a tidy necropolis. People slept on woollen mats and fur, made clothes of wool, flax and leather, and kept animals. The community was also especially fond of children: artefacts that were recovered included toys such as animals and rattles of clay, and small, clumsily crafted pots apparently made by children at playtime.

It is but two examples that underline that Old Europe was a civilisation millennia ahead of its neighbours. And Old Europe is a forgotten culture, as Richard Rudgeley has argued: “Old Europe was the precursor of many later cultural developments and […] the ancestral civilisation, rather than being lost beneath the waves through some cataclysmic geological event, was lost beneath the waves of invading tribes from the east.” Indeed, Rudgeley argued that when confronted with the “sudden arrival” of civilisation in Sumer or elsewhere, we should not look towards extra-terrestrial civilisation, nor Atlantis, but instead to “Old Europe”, a civilisation which the world seems intent on disregarding… and we can only wonder why.

“Civilisation” in Sumer was defined as the cultivation of crops and domestication of animals, with humans living a largely sedentary life, mostly in village or towns, with a type of central authority. With that definition of civilisation, it is clear that it did not begin in Sumer, but in Old Europe. Old Europe was a Neolithic civilisation, living of agriculture and the breeding of domestic animals. The most frequent domestic animals were cattle, although smaller goats, sheep and pigs were also bred. They also cultivated the most fertile prehistoric grain species. There was even a merchant economy: a surplus of products led to the development of trade with neighbouring regions, which supplied salt, obsidian or ornamental shells.

In fact, they were not actually a “Neolithic civilisation” – they were even further ahead of the times: in the region of Eastern Serbia, at Bele Vode and (the already discussed) Rudna Glava, in crevices and natural caves, the settlers of Vinca came in contact with copper ore which they began fashioning with fire, initially only for ornamental objects (beads and bracelets). They were more “Bronze Age” than “Stone Age”… this at a time when the rest of Europe and the Near East was not even a “Stone Age civilisation”.

One scholar, the already cited Marija Gimbutas, has highlighted the importance of Old Europe. So much so, that many consider her to have gone too far. She interpreted Old Europe as a civilisation of the Goddess, a concept which has taken on a life of its own in the modern New Age industry, extending far beyond anything Gimbutas herself could ever have imagined. Bernard Wailes stated how Gimbutas was "immensely knowledgeable but not very good in critical analysis... She amasses all the data and then leaps to conclusions without any intervening argument... Most of us tend to say, oh my God, here goes Marija again". But everyone agrees that her groundwork is solid, and it is from that which we build.

Gimbutas dated the civilisation of Old Europe from 6500 to 3500-3200 BC. It was at that time that the area was overrun by invading Indo-Europeans. The local population could do two things: remain and be ruled by new masters, or migrate, in search of new lands. It appears that the people of Old Europe did both: some went in search of a haven to the south, on the shores of the Aegean Sea, and beyond. Harald Haarmann has identified them as being responsible for the rise of the so-called Cycladic culture, as well as Crete, where the new settlers arrived around 3200 BC.

For Gimbutas, the difference between Old Europe and Indo-Europe was more than just one people invading another. It was the difference between a goddess-centred and matriarchal and the Bronze Age Indo-European patriarchal cultural elements. According to her interpretations, Old Europe was peaceful, they honoured homosexuals and they espoused economic equality. The Indo-Europeans were warmongering males. And it’s that conclusion with which many have great difficulty, for nothing is ever as distinct as that.

Today, artefacts of the Vinca culture grace the display cabinets of several museums, for they are magnificent ceramics – of an artistic and technological level which would not be equalled by other cultures for several millennia. It is believed that their writing originated out of sacred writing. Like Crete, they were a peaceful nation; Crete’s palaces had no defensive qualities.

The recovered artefacts of the Vinca culture equally show they had a profound spiritual life. The cult objects include figurines, sacrificial dishes, anthropomorphic and zoomorphic dishes. When we note that their number (over 1000 examples at Vinca alone) exceeds the total number of figurines discovered in the region of the Greek Aegean, we can only wonder why Old Europe is not better known today.

Life was represented on these objects as embodying the cycle of birth and death of Nature, along with the desire of man to get Nature's sympathy or to mollify it in the interest of survival. Shrines were discovered in Transylvania with complex architectural designs, indicating the involvedness of the rituals which were conducted in them. It may not have been a matriarchal, Goddess worshipping civilisation, but it was definitely a complex and established religious framework. Though nothing suggests it was a Goddess cult.

The same mistake has been made in Malta, where for generations certain statues were interpreted as “Mother Goddess” statues, whereas alternative thinkers as Joseph Ellul pointed out that there was nothing specifically feminine about these statues; that they showed a deity, but that it could equally be male or female. Recently, Ellul’s point of view has become shared by other experts on Malta, such as Dr. Caroline Malone, who argued that the theory that the Maltese temples were erected as part of a goddess-worshipping culture is no longer valid. In her opinion, Maltese prehistoric society was a relatively stable, agricultural community, living on an intense and densely populated island, which celebrated cyclical cycles of life, rites of passage, transitions between different stages of life, from separation to reintegration, fertility, ancestors, all of this within a cosmological context… and very much like Old Europe.

Around 3200 BC, the culture of Old Europe migrated, to the Aegean Sea and to Crete. Today, they are considered to be the origin of the Minoan civilisation, though it is a dimension that few Minoan scholars have included in their writing, instead largely opting to see Crete as yet another “stand alone” civilisation. Gimbutas stated that: “the civilisation that flourished in Old Europe between 6500 and 3500 BC and in Crete until 1450 BC enjoyed a long period of uninterrupted peaceful living.” Motifs such as the snake, intertwined with the bird goddess motif, the bee and the butterfly, with the distinctive motif of the double axe, are found both in Old Europe and Crete. But the best evidence is in the writing of Old Europe and the Linear A script of Crete, which are to all intents and purposes identical.

But it is equally clear that contacts between Sumer and Old Europe existed at the time of the Ubaid culture, in Eridu – the site which inspired Sitchin so greatly in his formulation of the Annunaki theory and his identification of these statues as “Nephilim”. The Ubaid culture is ca. 4500 BC and though we should perhaps not go as far as concluding that Sumer was a child of Old Europe, the two cultures obviously knew each other. Indeed, in recent years, Old European artefacts were even discovered in Southeastern France, suggesting that the civilisation of Old Europe travelled not merely to the East, but also to the West. Perhaps we should even consider them to be at the origin of the megalithic civilisation? But no-one, it seems, has dared to topple that stone yet.

The Cradle of Europe

Redheaded Venus of Vinca

The exhibition consists of masterpieces from three successive cultures: Lepenski Vir, Starčevo and Vinča. These cultures and their art represent three critical phases in the creation of Europe as we know it.

►Lepenski Vir is famous for the oldest permanent buildings and sedentary community in Europe as well as the first monumental art created after the Ice Age. Lepenski Vir is the site of the seminal art and architecture for every city from Paris to Belgrade - and beyond.

►Starčevo, which follows Lepenski Vir, is a culture named after a village near Grad. It represents the vanguard of the Neolithic’s advance into Europe and introduced a panoply of technologies and symbols that found their consummate expression in refined ceramic sculptures.

►Vinča, the most recent of the three cultures, which is named after a site within greater Belgrade, erupted onto the scene with the oldest European metallurgy. The metallurgical revolution led to a cultural explosion on a continental scale, involving the first long-range trade networks and the seeds of a culture spread by metallurgical magicians to western Europe. Vinča’s art is as powerful in its angular abstraction as Africa’s, and its clay tablets covered in magical symbols may have spawned several modern alphabets.

... three advances in the cradle of Europe: from the first settlements to the first beliefs and networks to embrace Europeans as a whole.

The exhibition is being organized by Duncan Caldwell, as curator, and Ljubomir Peškirević, coordinating associate, under the auspices of the Serbian Ministry of Culture and the Mayor of Belgrade. Jelena Mitrović is the Belgrade liaison with the Serbian archeological community and authorities.

1 - LEPENSKI VIR – THE OMPHALOS OF MONUMENTAL ART & SETTLEMENT IN EUROPE

Today, black holes sucking in solar systems and hypothetically spawning universes have become the latest version of an ancient symbol of destruction and rejuvenation: the maelstrom sucking everything around it into oblivion, only to have flotsam miraculously reappear downstream. A huge trapezoidal cliff named Treskavek on the left bank of the Danube marks the location of such a whirlpool. Directly facing the striking landmark and terrifying suction at its foot is a sandy horseshoe-shaped terrace with stone edifices arranged in a fan at the base of Korsho hill. The entrances of the buildings, whose shapes all echo that of the cliff across the river, are located at the wide ends that open towards the whirlpool. One or two monumental sculptures of anthropomorphized fish-deities graced with arabesques, whirlpool spirals and pronounced vulvas stand beyond the central basin and hearth at the narrow end of each building, facing the river outside. Under these sentinels and lime plaster floors, that show signs of being burnished with red and white pigments, lie skeletons – usually of a single elder who seems to have been buried behind the fireplace just before the house was abandoned, but sometimes including newborns.

We are at Lepenski Vir – a site named after the whirlpool, or “vir” in Serbian, that lies off its shore. Six or seven settlements consisting of a total of 136 of these parallelepiped edifices stood here successively from 6400 BC until 4900 BC with art being produced in the hunter-gatherer villages that lasted from approximately 6230 to 5380 BC – as opposed to the first and last villages, which had no art. For those 8 art-producing centuries, the site was constantly rebuilt and revisited between floods for burials and other rituals, making it the oldest full-time cult center in all of Europe. The first sedentary villages on the continent formed around the site’s core, with their inhabitants living in one place year-round even before the introduction of agriculture due to the profusion of fish provided by the gorge.

Here, in the picturesque Iron Gates, which form one of Europe’s most strategic choke-points, the Danube suddenly goes from being a sluggish expanse over a kilometer across to a current full of life. And symbolism. Here in the cradle of Europe as we know it, lies the ancestor of every European village and town.

The community around Lepenski Vir was just as pivotal for the arts. For thousands of years after the Ice Age, no monumental stone sculpture in the round had been made anywhere on the continent. Surviving works from this hunter-gatherer period, which is called the Mesolithic, are usually small and abstract and consist of bones and pebbles that have been incised or painted with ochre. But here, at Lepenski Vir, stone sculpture on a monumental scale was carved once again – to continue uninterrupted to the present day. From Rodin’s “Thinker” to caryatides holding up balconies, all the large-scale art which surrounds us derives from a tradition that was first expressed through the fish deities of Lepenski Vir.

The exhibition will gather these seminal masterpieces with features drawn from fish, pregnant women and eggs. It will explore how their symbolism may derive from a belief that the whirlpool was a birth-canal into the afterlife as well as a supernaturally powerful vulva giving birth to the bountiful life of the majestic gorge.

The part of the show devoted to Lepenski Vir will also relate the dramatic history of the site’s discovery by Professor Dragoslav Srejović as the Danube was rising behind a new dam. It all started with the observation in 1960 of Neolithic shards among the foundations of one of the numerous small forts that had guarded the Roman frontier. When the dam was started downstream, this pivotal site for understanding the roots of Europe’s identity almost disappeared un-remarked except for an arbitrary decision in 1965 to perform salvage archeology because of the fort – when other forts nearby were ignored. Even then, it took another two years before the Mesolithic layers and their art awoke archeologists to what was at stake. In a last-ditch effort, the site was moved 30 meters uphill in a feat reminiscent of the raising of Abu Simbel.

The site also has its mysteries. To some, the burials of newborns suggest infant sacrifices. But others vociferously argue that the same burials show signs of unusual care and respect for children who had died in infancy. The exhibition will illustrate the debate – and try to answer it.

Controversy has also raged because a few shards of pottery - a Neolithic technology - have been found even in the earliest levels. Two contrasting explanations have been offered: one, that they are intrusions that have slipped in from above, and, two, that Lepenski Vir was in precocious contact with cultures in far away Anatolia which had already entered the Neolithic. Either way, Lepenski Vir is pivotal: its art and buildings are unique, making it one of the main roots of later developments in Europe - but it may also have been the first European site to establish indirect links with Asia.

Finally, studies of the dead both in the settled area and the large adjacent cemetery suggest that Lepenski Vir may have been the last European Shangri-la, with life-expectancies which would not be seen again until the advent of modern medicine and none of the deformities and stunting associated with the repetitive activities and poor diets of the later Neolithic and industrial eras. An ecological moral as important as the turning points represented by Lepenski Vir’s settlements and art may await us in the cradle of Europe.

2 - STARCEVO & THE ART OF THE NEOLITHIC VANGUARD IN EUROPE

The Neolithic and agricultural revolutions gained their first firm footholds in Europe, spreading into the Balkans from the Middle East and Thrace, with the development of the Starčevo - Körös Culture which overlapped the culture of Lepenski Vir. Perhaps more importantly, Starčevo straddles a natural catastrophe around 5600 BC that was so great that it probably triggered flood myths that have survived to this day: the sudden brimming over of the Mediterranean into the vast basin which has become the Black Sea.

Around the fresh water lake that lay below sea level at the center of the basin was certainly one of the most fertile and densely populated zones of the newly born Neolithic. As a result of glacial melting due both to the end of the Ice Age and greenhouse gases released by the massive felling of forests for agriculture and the proliferation of flatulent cattle following their domestication, sea levels had been rising. Finally, a trickle worked its way from the Mediterranean across the land bridge at the Bosporus. Within a day, a cascade 200 times greater than Niagara burst into the Neolithic paradise. The cataclysm created such a din that it could be heard 480 kilometers away. The flashflood rose 15 cm. a day over 97,000 square kilometers of prime agricultural land, drowning their civilizations and sending refugees rushing for the highlands.

In the heart of the Balkans, technologies – and, in certain respects, even the arts - leapt in sophistication. The probable fertilizing influence of sophisticated refugees can be compared to the aftermath of the second fall of Constantinople, when its intelligentsia fled with classical texts that had not been seen in Rome for a millennium. Just as such refugees helped trigger the Renaissance, the ones from the Black Sea diaspora probably helped transform a cultural backwater into the new center of European civilization. Although Starčevo’s artists had managed to produce masterpieces from the start, creating steatopygous statuettes of women similar to ones from Thrace and Anatolia and miniaturized temples whose « chimneys » are human heads, the stage was set for breakthroughs which would resound through Europe. The show will illustrate these shifts through works from both before and after the cataclysm, while focusing on presenting visually powerful works of art – with only a small number of “technical” pieces to put masterpieces into context.

3 - VINCA – THE FIRST EUROPEAN CROSSROADS

Vinča – the first culture to master metallurgy in Europe - was the result of this renaissance. As Starčevo’s culture declined, the new culture sprang into existence, expanding and lasting from 5400 BC to at least 3800 BC. For generations, researchers have argued whether the revolution that took place during the shift was indigenous or due to immigrants. But now that the flooding of the Black Sea basin has been dated to the decades just before Vinča, it is evident that waves of refugees bearing new thinking must have influenced any changes that were occurring indigenously. Economics also drove the change as trade was redirected from the northeast to the south via the Morava Valley. Vinča, on the right bank of the Danube 13 kilometers southeast of central Belgrade, was better placed to take advantage of this shift than Starčevo which was farther from the new source of wealth, on the opposite bank upstream. More importantly, the trade network grew more complex, bore more goods and gradually began to broaden.

Two finds from the oldest Vinča-culture level at the new type-site underscore the swelling revolution. First there are fluted and black pots that were fired to high temperatures in closed ovens, making them more durable than the older culture’s low-fired specimens that were either painted white or dark brown on red. Strangely, many of the new streamlined pots look like they were inspired by metal examples. But, at first glance, it is hard to imagine where such ancient potters could have seen metal vessels. A clue may lie in the fact that M. Vasič, the site’s first official excavator, from 1908 to 1913 and, again, from 1929 to 1934, discovered equally old circular cavities that had been used to heat a pigment, galena – which is, coincidentally, also a lead-bearing ore. What is certain is that ovens that had first been enclosed and improved to harden pottery led to the discovery no more than 300 years later that another pigment, green malachite, could be coaxed into yielding an even more exotic substance - copper.

But the new culture had burgeoned in terms of expanding trade networks, number of settlements and overall population long before the breakthrough. The sophisticated new pottery replaced the cruder type even at Starčevo, although it didn’t save that site from being abandoned shortly thereafter. Starčevo-type ceramics also occur at the base of the Vinča mound, in layers 8 to 11.4 meters deep, but underlie 7 more meters covering 2 early phases, a transitional layer, and 2 later phases of Vinča occupation, which together lasted over a millennium. The oldest of the phases, which Vasič called Level A, consisted of a settlement of four-sided adobe huts within a protective ditch. By Level B, the village covered 6 hectares and was organized along an axis with bigger buildings than before. Then, after almost six centuries of apparent peace for Vinča villages on the mound, the last Phase B buildings were burnt around 4800 BC.

The discovery of copper around 200 years before may have had something to do with the destruction of the settlement. In 2001, Dusan Sljivar and Dragan Jacanovič conducted a remarkable excavation at Belo Vode which proved that the Vinča settlement there had grown to over 700 buildings spread over 100 hectares by smelting copper ore from a mine at Belo Lice. Belo Vode and other smelting centers such as Konjussnica, Vitezzevo and Pločnik near Prokuplje boomed, becoming the industrial capitals of Europe. The breakthrough had put Vinča itself, which lies just to the west of the first Vinča malachite mine to be discovered, Rudna Glava, near Madjanpek, in an even more strategic position as metal jewelry and tools were traded up the Danube towards western Europe. But the wealth that came with Vinča’s position must have made it a tempting target for competing centers. The fact that the transitional layer above the ashes of Level B is named after Gradac, a site in the Morava Valley, which produced identifiable engraved pottery, suggests that the type-site near Belgrade was burned by invaders from a southern branch of the same culture as the mother site attracted covetous eyes and threatened to become too influential.

Despite the destruction and brief occupation, Vinča’s enviable position helped it bounce back richer than ever in Phase C, spurring both the diffusion of metallurgy and the creation of social disparities. While such cultural indicators as Vinča’s streamlined black pottery and cruciform statuettes only change slightly from B to C, its houses change drastically, becoming more varied in size and design, with some of the more substantial trapezoidal and rectangular structures even including porches.

Trade was booming throughout the Vinča cultural sphere, which extended from the Tisza Valley in Hungary to Macedonia in the south and from eastern Bosnia to Transylvania in the west, occupying the whole of the central Balkans. A trading hub and ritual center grew in every major valley or plain. In central Serbia, the first center was Vinča – then after it was burned around 3800 BC - along with other centers to the north - Banjica took over for the last 2 centuries of the culture’s existence. Similarly, Gradac was the first center of the Leskovac Basin, until being displaced by Pločinik. The first center in the Kosmet « province » was Predionica, which was followed by Valač, while, in the Mureč Valley, Turdač gave way to Tartaria. Potporanj became the main center in its region along the present Romanian border while Gomolava became the hub of the Sava Valley.

Around each center, more settlements were founded, with over 600 known so far. While the Vinča culture was amazingly homogeneous in its material culture over space and time, indicating a strong ethnic and perhaps even “national” identity that survived for nearly 1500 years, the villages varied greatly due to local conditions. Sites on major rivers, like Vinča, which prospered because of their location on trade arteries, usually remained under a dozen hectares despite populations of up to 2000 people, in order to conserve arable land for horticulture, animal husbandry, and even hunting which represented 10% of villagers’ diets. Along the Romanian border around Banat as well as along the Sava, annual floods forced villagers to abandon and reclaim their settlements seasonally. To the west of the Morava and in western Serbia, where pastures and fields of rye, wheat, barley, millet, and oats, as well as peas, lentils and flax could stretch to the horizon, some settlements sprawled over more than 25 hectares. In rugged areas, though, such as the hills of Transylvania and Bosnia, the earliest Vinča sites were only way stations of cattle-driving nomads. But as demand for the mineral pigments and ores in the surrounding mountains shot up, some of these camps became permanent.

Trade in exotic materials was turning Vinča into the center of the most extensive European exchange system that had ever existed. Obsidian was brought in from Tokai in the upper Tisza region of Hungary, while black flint was imported all the way from Moldavia via Transylvania. From the opposite direction, spondylus shells for the manufacture of beads arrived from the Mediterranean. The alabaster used to make two statuettes found in a ceremonial pit in Tartaria must have followed the same route. Crystal came from the Rudnik Mountains while salt was exported from Vinča sites in Bosnia via Tuszla. Finally, trade in pigments like cinnabar, vermilion from Suplja Stena, galena and malachite, certainly led to the discovery of two by-products, lead and copper, triggering another wave of even more extensive commerce.

The discovery of smelting gave the Vinča culture - already one of the most dynamic in Europe - a near monopoly. The production of the first metal tools and jewelry unleashed a rush by cultures as far as the Atlantic and Baltic to possess Balkan products. Like the Hallstatt culture, which would later sit at the heart of one of Europe’s richest trade networks during the transition from the Bronze to the Iron Age, because of its salt deposits, Vinča was momentarily in the enviable position of possessing a technology and material unknown to anyone else. Soon, cultures as far away as Scandinavia were doing their best to imitate Balkan copper axes and daggers – but rather desperately in stone. The appetite for copper objects stimulated indirect trade with the amber-producing areas around the Baltic, extending elaborate networks and creating the first consistent trans-continental exchange system. In the meantime, coppersmith magicians noted for a particular set of grave goods, including characteristic bell beakers, spread throughout western Europe, remaining mysteriously apart from the populations they traveled amongst, at least when they were enterred in distinct tombs.

At the center of these trade networks and ideological ripples lay a culture of startling originality. The exhibition will show maternities whose mothers and babies have mask-like faces and are 4,500 years older than their Christian equivalents. Then there are Siamese twin statues with double heads. And “dollhouse” temples with bullhorn protomes similar to a 13.5-by-6 meter, late-Vinča building at the type-site that had a hearth in each of its five rooms and a bucranium like ones found across the Black Sea at Çatal Höyük.

Ethnological studies relating the types of buildings used by modern tribes to their family structures suggest that such long houses with multiple hearths are almost exclusively found in matrilineal and matrilocal societies where a house is inhabited by the families of several sisters. In such societies, the sisters’ mother often reigns over the long-house, suggesting both the power of Vinča matrons and the inspiration for Vinča’s striking sculptures of female supernaturals with mask-like heads.

Covering the statues’ clothing and tablets are a plethora of signs – signs which Marija Gimbutas believed formed a proto-alphabet to convey the “language of the Goddess”. Although the theory remains highly controversial, there is no doubt that the signs on Vinča tablets found at Tartaria must be distantly related to ones on nearly identical tablets with the same types of registers found thousands of kilometers away at Obaid near Ur in Mesopotamia. In Mesopotamia such symbols contributed to the evolution of cuneiform, while in the Balkans and Levant the tendency towards such signing eventually led to Linear A, which gave rise to the modern European alphabets. The link between the symbols and tablets may again have been refugees from the Great Flood.

But the advance of metallurgy during Phase C also strengthened cultures in mineralogically richer zones to the east that could specialize in production. Despite the discovery of slag and metal products at such Vinča sites as Selevac and Gomolava, the culture centered in Serbia was far more active in diffusing the new goods than producing them. Partly as a consequence, the Bulgarian Marica-Karanova V culture extended its influence along the Maritsa, then along the east bank of the Morava – enriching the Vinča sphere even as it encroached upon it. The initiative passed definitively to Varna and other metal-working centers near the mouth of the Danube once the Gumelnitsa and Karanova VI cultures of Bulgaria and southern Romania began to exploit mines at Aibunar and Stara Zagora in the second half of the 5th millennium. While Vinča was gradually forced to withdraw to the west of the Morava and abandon it’s type-site for Banjica, Varna was lavishing its dead with thousands of prestige goods made of copper and Transylvanian gold. Although the Vinča culture survived for another two centuries after the type-site’s burning around 3800 BC, it had run its course.

But what a legacy it has left us! First there’s its example of technological prowess.

Then, there’s Vinča’s legacy of settlements trading peacefully at the heart of a European exchange system for centuries at a time even though most of its communities weren’t even enclosed. http://www.duncancaldwell.com/Site/Prehistory_Shows.html

The exhibition consists of masterpieces from three successive cultures: Lepenski Vir, Starčevo and Vinča. These cultures and their art represent three critical phases in the creation of Europe as we know it.

►Lepenski Vir is famous for the oldest permanent buildings and sedentary community in Europe as well as the first monumental art created after the Ice Age. Lepenski Vir is the site of the seminal art and architecture for every city from Paris to Belgrade - and beyond.

►Starčevo, which follows Lepenski Vir, is a culture named after a village near Grad. It represents the vanguard of the Neolithic’s advance into Europe and introduced a panoply of technologies and symbols that found their consummate expression in refined ceramic sculptures.

►Vinča, the most recent of the three cultures, which is named after a site within greater Belgrade, erupted onto the scene with the oldest European metallurgy. The metallurgical revolution led to a cultural explosion on a continental scale, involving the first long-range trade networks and the seeds of a culture spread by metallurgical magicians to western Europe. Vinča’s art is as powerful in its angular abstraction as Africa’s, and its clay tablets covered in magical symbols may have spawned several modern alphabets.

... three advances in the cradle of Europe: from the first settlements to the first beliefs and networks to embrace Europeans as a whole.

The exhibition is being organized by Duncan Caldwell, as curator, and Ljubomir Peškirević, coordinating associate, under the auspices of the Serbian Ministry of Culture and the Mayor of Belgrade. Jelena Mitrović is the Belgrade liaison with the Serbian archeological community and authorities.

1 - LEPENSKI VIR – THE OMPHALOS OF MONUMENTAL ART & SETTLEMENT IN EUROPE

Today, black holes sucking in solar systems and hypothetically spawning universes have become the latest version of an ancient symbol of destruction and rejuvenation: the maelstrom sucking everything around it into oblivion, only to have flotsam miraculously reappear downstream. A huge trapezoidal cliff named Treskavek on the left bank of the Danube marks the location of such a whirlpool. Directly facing the striking landmark and terrifying suction at its foot is a sandy horseshoe-shaped terrace with stone edifices arranged in a fan at the base of Korsho hill. The entrances of the buildings, whose shapes all echo that of the cliff across the river, are located at the wide ends that open towards the whirlpool. One or two monumental sculptures of anthropomorphized fish-deities graced with arabesques, whirlpool spirals and pronounced vulvas stand beyond the central basin and hearth at the narrow end of each building, facing the river outside. Under these sentinels and lime plaster floors, that show signs of being burnished with red and white pigments, lie skeletons – usually of a single elder who seems to have been buried behind the fireplace just before the house was abandoned, but sometimes including newborns.

We are at Lepenski Vir – a site named after the whirlpool, or “vir” in Serbian, that lies off its shore. Six or seven settlements consisting of a total of 136 of these parallelepiped edifices stood here successively from 6400 BC until 4900 BC with art being produced in the hunter-gatherer villages that lasted from approximately 6230 to 5380 BC – as opposed to the first and last villages, which had no art. For those 8 art-producing centuries, the site was constantly rebuilt and revisited between floods for burials and other rituals, making it the oldest full-time cult center in all of Europe. The first sedentary villages on the continent formed around the site’s core, with their inhabitants living in one place year-round even before the introduction of agriculture due to the profusion of fish provided by the gorge.

Here, in the picturesque Iron Gates, which form one of Europe’s most strategic choke-points, the Danube suddenly goes from being a sluggish expanse over a kilometer across to a current full of life. And symbolism. Here in the cradle of Europe as we know it, lies the ancestor of every European village and town.

The community around Lepenski Vir was just as pivotal for the arts. For thousands of years after the Ice Age, no monumental stone sculpture in the round had been made anywhere on the continent. Surviving works from this hunter-gatherer period, which is called the Mesolithic, are usually small and abstract and consist of bones and pebbles that have been incised or painted with ochre. But here, at Lepenski Vir, stone sculpture on a monumental scale was carved once again – to continue uninterrupted to the present day. From Rodin’s “Thinker” to caryatides holding up balconies, all the large-scale art which surrounds us derives from a tradition that was first expressed through the fish deities of Lepenski Vir.

The exhibition will gather these seminal masterpieces with features drawn from fish, pregnant women and eggs. It will explore how their symbolism may derive from a belief that the whirlpool was a birth-canal into the afterlife as well as a supernaturally powerful vulva giving birth to the bountiful life of the majestic gorge.

The part of the show devoted to Lepenski Vir will also relate the dramatic history of the site’s discovery by Professor Dragoslav Srejović as the Danube was rising behind a new dam. It all started with the observation in 1960 of Neolithic shards among the foundations of one of the numerous small forts that had guarded the Roman frontier. When the dam was started downstream, this pivotal site for understanding the roots of Europe’s identity almost disappeared un-remarked except for an arbitrary decision in 1965 to perform salvage archeology because of the fort – when other forts nearby were ignored. Even then, it took another two years before the Mesolithic layers and their art awoke archeologists to what was at stake. In a last-ditch effort, the site was moved 30 meters uphill in a feat reminiscent of the raising of Abu Simbel.

The site also has its mysteries. To some, the burials of newborns suggest infant sacrifices. But others vociferously argue that the same burials show signs of unusual care and respect for children who had died in infancy. The exhibition will illustrate the debate – and try to answer it.

Controversy has also raged because a few shards of pottery - a Neolithic technology - have been found even in the earliest levels. Two contrasting explanations have been offered: one, that they are intrusions that have slipped in from above, and, two, that Lepenski Vir was in precocious contact with cultures in far away Anatolia which had already entered the Neolithic. Either way, Lepenski Vir is pivotal: its art and buildings are unique, making it one of the main roots of later developments in Europe - but it may also have been the first European site to establish indirect links with Asia.

Finally, studies of the dead both in the settled area and the large adjacent cemetery suggest that Lepenski Vir may have been the last European Shangri-la, with life-expectancies which would not be seen again until the advent of modern medicine and none of the deformities and stunting associated with the repetitive activities and poor diets of the later Neolithic and industrial eras. An ecological moral as important as the turning points represented by Lepenski Vir’s settlements and art may await us in the cradle of Europe.

2 - STARCEVO & THE ART OF THE NEOLITHIC VANGUARD IN EUROPE

The Neolithic and agricultural revolutions gained their first firm footholds in Europe, spreading into the Balkans from the Middle East and Thrace, with the development of the Starčevo - Körös Culture which overlapped the culture of Lepenski Vir. Perhaps more importantly, Starčevo straddles a natural catastrophe around 5600 BC that was so great that it probably triggered flood myths that have survived to this day: the sudden brimming over of the Mediterranean into the vast basin which has become the Black Sea.

Around the fresh water lake that lay below sea level at the center of the basin was certainly one of the most fertile and densely populated zones of the newly born Neolithic. As a result of glacial melting due both to the end of the Ice Age and greenhouse gases released by the massive felling of forests for agriculture and the proliferation of flatulent cattle following their domestication, sea levels had been rising. Finally, a trickle worked its way from the Mediterranean across the land bridge at the Bosporus. Within a day, a cascade 200 times greater than Niagara burst into the Neolithic paradise. The cataclysm created such a din that it could be heard 480 kilometers away. The flashflood rose 15 cm. a day over 97,000 square kilometers of prime agricultural land, drowning their civilizations and sending refugees rushing for the highlands.

In the heart of the Balkans, technologies – and, in certain respects, even the arts - leapt in sophistication. The probable fertilizing influence of sophisticated refugees can be compared to the aftermath of the second fall of Constantinople, when its intelligentsia fled with classical texts that had not been seen in Rome for a millennium. Just as such refugees helped trigger the Renaissance, the ones from the Black Sea diaspora probably helped transform a cultural backwater into the new center of European civilization. Although Starčevo’s artists had managed to produce masterpieces from the start, creating steatopygous statuettes of women similar to ones from Thrace and Anatolia and miniaturized temples whose « chimneys » are human heads, the stage was set for breakthroughs which would resound through Europe. The show will illustrate these shifts through works from both before and after the cataclysm, while focusing on presenting visually powerful works of art – with only a small number of “technical” pieces to put masterpieces into context.

3 - VINCA – THE FIRST EUROPEAN CROSSROADS

Vinča – the first culture to master metallurgy in Europe - was the result of this renaissance. As Starčevo’s culture declined, the new culture sprang into existence, expanding and lasting from 5400 BC to at least 3800 BC. For generations, researchers have argued whether the revolution that took place during the shift was indigenous or due to immigrants. But now that the flooding of the Black Sea basin has been dated to the decades just before Vinča, it is evident that waves of refugees bearing new thinking must have influenced any changes that were occurring indigenously. Economics also drove the change as trade was redirected from the northeast to the south via the Morava Valley. Vinča, on the right bank of the Danube 13 kilometers southeast of central Belgrade, was better placed to take advantage of this shift than Starčevo which was farther from the new source of wealth, on the opposite bank upstream. More importantly, the trade network grew more complex, bore more goods and gradually began to broaden.

Two finds from the oldest Vinča-culture level at the new type-site underscore the swelling revolution. First there are fluted and black pots that were fired to high temperatures in closed ovens, making them more durable than the older culture’s low-fired specimens that were either painted white or dark brown on red. Strangely, many of the new streamlined pots look like they were inspired by metal examples. But, at first glance, it is hard to imagine where such ancient potters could have seen metal vessels. A clue may lie in the fact that M. Vasič, the site’s first official excavator, from 1908 to 1913 and, again, from 1929 to 1934, discovered equally old circular cavities that had been used to heat a pigment, galena – which is, coincidentally, also a lead-bearing ore. What is certain is that ovens that had first been enclosed and improved to harden pottery led to the discovery no more than 300 years later that another pigment, green malachite, could be coaxed into yielding an even more exotic substance - copper.

But the new culture had burgeoned in terms of expanding trade networks, number of settlements and overall population long before the breakthrough. The sophisticated new pottery replaced the cruder type even at Starčevo, although it didn’t save that site from being abandoned shortly thereafter. Starčevo-type ceramics also occur at the base of the Vinča mound, in layers 8 to 11.4 meters deep, but underlie 7 more meters covering 2 early phases, a transitional layer, and 2 later phases of Vinča occupation, which together lasted over a millennium. The oldest of the phases, which Vasič called Level A, consisted of a settlement of four-sided adobe huts within a protective ditch. By Level B, the village covered 6 hectares and was organized along an axis with bigger buildings than before. Then, after almost six centuries of apparent peace for Vinča villages on the mound, the last Phase B buildings were burnt around 4800 BC.

The discovery of copper around 200 years before may have had something to do with the destruction of the settlement. In 2001, Dusan Sljivar and Dragan Jacanovič conducted a remarkable excavation at Belo Vode which proved that the Vinča settlement there had grown to over 700 buildings spread over 100 hectares by smelting copper ore from a mine at Belo Lice. Belo Vode and other smelting centers such as Konjussnica, Vitezzevo and Pločnik near Prokuplje boomed, becoming the industrial capitals of Europe. The breakthrough had put Vinča itself, which lies just to the west of the first Vinča malachite mine to be discovered, Rudna Glava, near Madjanpek, in an even more strategic position as metal jewelry and tools were traded up the Danube towards western Europe. But the wealth that came with Vinča’s position must have made it a tempting target for competing centers. The fact that the transitional layer above the ashes of Level B is named after Gradac, a site in the Morava Valley, which produced identifiable engraved pottery, suggests that the type-site near Belgrade was burned by invaders from a southern branch of the same culture as the mother site attracted covetous eyes and threatened to become too influential.

Despite the destruction and brief occupation, Vinča’s enviable position helped it bounce back richer than ever in Phase C, spurring both the diffusion of metallurgy and the creation of social disparities. While such cultural indicators as Vinča’s streamlined black pottery and cruciform statuettes only change slightly from B to C, its houses change drastically, becoming more varied in size and design, with some of the more substantial trapezoidal and rectangular structures even including porches.

Trade was booming throughout the Vinča cultural sphere, which extended from the Tisza Valley in Hungary to Macedonia in the south and from eastern Bosnia to Transylvania in the west, occupying the whole of the central Balkans. A trading hub and ritual center grew in every major valley or plain. In central Serbia, the first center was Vinča – then after it was burned around 3800 BC - along with other centers to the north - Banjica took over for the last 2 centuries of the culture’s existence. Similarly, Gradac was the first center of the Leskovac Basin, until being displaced by Pločinik. The first center in the Kosmet « province » was Predionica, which was followed by Valač, while, in the Mureč Valley, Turdač gave way to Tartaria. Potporanj became the main center in its region along the present Romanian border while Gomolava became the hub of the Sava Valley.

Around each center, more settlements were founded, with over 600 known so far. While the Vinča culture was amazingly homogeneous in its material culture over space and time, indicating a strong ethnic and perhaps even “national” identity that survived for nearly 1500 years, the villages varied greatly due to local conditions. Sites on major rivers, like Vinča, which prospered because of their location on trade arteries, usually remained under a dozen hectares despite populations of up to 2000 people, in order to conserve arable land for horticulture, animal husbandry, and even hunting which represented 10% of villagers’ diets. Along the Romanian border around Banat as well as along the Sava, annual floods forced villagers to abandon and reclaim their settlements seasonally. To the west of the Morava and in western Serbia, where pastures and fields of rye, wheat, barley, millet, and oats, as well as peas, lentils and flax could stretch to the horizon, some settlements sprawled over more than 25 hectares. In rugged areas, though, such as the hills of Transylvania and Bosnia, the earliest Vinča sites were only way stations of cattle-driving nomads. But as demand for the mineral pigments and ores in the surrounding mountains shot up, some of these camps became permanent.

Trade in exotic materials was turning Vinča into the center of the most extensive European exchange system that had ever existed. Obsidian was brought in from Tokai in the upper Tisza region of Hungary, while black flint was imported all the way from Moldavia via Transylvania. From the opposite direction, spondylus shells for the manufacture of beads arrived from the Mediterranean. The alabaster used to make two statuettes found in a ceremonial pit in Tartaria must have followed the same route. Crystal came from the Rudnik Mountains while salt was exported from Vinča sites in Bosnia via Tuszla. Finally, trade in pigments like cinnabar, vermilion from Suplja Stena, galena and malachite, certainly led to the discovery of two by-products, lead and copper, triggering another wave of even more extensive commerce.

The discovery of smelting gave the Vinča culture - already one of the most dynamic in Europe - a near monopoly. The production of the first metal tools and jewelry unleashed a rush by cultures as far as the Atlantic and Baltic to possess Balkan products. Like the Hallstatt culture, which would later sit at the heart of one of Europe’s richest trade networks during the transition from the Bronze to the Iron Age, because of its salt deposits, Vinča was momentarily in the enviable position of possessing a technology and material unknown to anyone else. Soon, cultures as far away as Scandinavia were doing their best to imitate Balkan copper axes and daggers – but rather desperately in stone. The appetite for copper objects stimulated indirect trade with the amber-producing areas around the Baltic, extending elaborate networks and creating the first consistent trans-continental exchange system. In the meantime, coppersmith magicians noted for a particular set of grave goods, including characteristic bell beakers, spread throughout western Europe, remaining mysteriously apart from the populations they traveled amongst, at least when they were enterred in distinct tombs.

At the center of these trade networks and ideological ripples lay a culture of startling originality. The exhibition will show maternities whose mothers and babies have mask-like faces and are 4,500 years older than their Christian equivalents. Then there are Siamese twin statues with double heads. And “dollhouse” temples with bullhorn protomes similar to a 13.5-by-6 meter, late-Vinča building at the type-site that had a hearth in each of its five rooms and a bucranium like ones found across the Black Sea at Çatal Höyük.

Ethnological studies relating the types of buildings used by modern tribes to their family structures suggest that such long houses with multiple hearths are almost exclusively found in matrilineal and matrilocal societies where a house is inhabited by the families of several sisters. In such societies, the sisters’ mother often reigns over the long-house, suggesting both the power of Vinča matrons and the inspiration for Vinča’s striking sculptures of female supernaturals with mask-like heads.

Covering the statues’ clothing and tablets are a plethora of signs – signs which Marija Gimbutas believed formed a proto-alphabet to convey the “language of the Goddess”. Although the theory remains highly controversial, there is no doubt that the signs on Vinča tablets found at Tartaria must be distantly related to ones on nearly identical tablets with the same types of registers found thousands of kilometers away at Obaid near Ur in Mesopotamia. In Mesopotamia such symbols contributed to the evolution of cuneiform, while in the Balkans and Levant the tendency towards such signing eventually led to Linear A, which gave rise to the modern European alphabets. The link between the symbols and tablets may again have been refugees from the Great Flood.

But the advance of metallurgy during Phase C also strengthened cultures in mineralogically richer zones to the east that could specialize in production. Despite the discovery of slag and metal products at such Vinča sites as Selevac and Gomolava, the culture centered in Serbia was far more active in diffusing the new goods than producing them. Partly as a consequence, the Bulgarian Marica-Karanova V culture extended its influence along the Maritsa, then along the east bank of the Morava – enriching the Vinča sphere even as it encroached upon it. The initiative passed definitively to Varna and other metal-working centers near the mouth of the Danube once the Gumelnitsa and Karanova VI cultures of Bulgaria and southern Romania began to exploit mines at Aibunar and Stara Zagora in the second half of the 5th millennium. While Vinča was gradually forced to withdraw to the west of the Morava and abandon it’s type-site for Banjica, Varna was lavishing its dead with thousands of prestige goods made of copper and Transylvanian gold. Although the Vinča culture survived for another two centuries after the type-site’s burning around 3800 BC, it had run its course.

But what a legacy it has left us! First there’s its example of technological prowess.

Then, there’s Vinča’s legacy of settlements trading peacefully at the heart of a European exchange system for centuries at a time even though most of its communities weren’t even enclosed. http://www.duncancaldwell.com/Site/Prehistory_Shows.html

(c) 2011-2014,

All Rights Reserved for Original Multimedia, Graphic & Written Content.

[email protected]

For Educational Purposes Only.

Materials mirrored here under "Fair Use" for Educational Purposes Only.

Fair Use Notice