XIONGNU

Dragon Lake, Siberia

http://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/Dragon-Lake-Siberia.jpg

http://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/Dragon-Lake-Siberia.jpg

According to the New Book of Tang, the Ashina were related to the northern tribes of the Xiongnu ... Ashina was one of ten sons born to a grey she-wolf ... Xiongnu (Hsiung-nu) were led by a chief called

shan-yü, whose full title transcribed into Chinese is Ch'eng-li Ku-t'u

Shan-yü, words which the Chinese translate as "Majesty Son of Heaven".

In these words may be detected Turko-Mongol roots: ch'eng-li in

particular is the transcription of the Turkic and Mongol word Tängri,

Heaven or God.

The cultural affinity of the Xiongnu was with the peoples of southern

Siberia and Central Asia; with the Chinese they exchanged arrows rather

than culture. Even here the two worlds differed: the Xiongnu shot with

hand bows, while Chinese employed crossbows. Nomadic art influenced

Chinese more than Chinese art influenced Xiongnu. "Animal style" motifs

are occasionally found in the art of Han China, borrowed from their

nomadic neighbours. Lev Gumilev

elaborates the roots of the Chinese cultural influence found in the

Noin-Ula cemetery. The Chinese culture was spread not only by material

objects, but also by population admixture. The Chinese migrated

continuously to the steppes, the first big wave arriving in the 3rd c.

BC during the Tsin dynasty (Pin. Qin),

when captured Chinese became subjects of the Chanuys, a process

repeated during the following centuries. Chinese women married Chanuys,

princes, and nobles, and their entourages brought Chinese tastes and

ideas. The numerous deserters who entered Chanuy service (for example,

Vey Lüy, Li Lin) also taught the Huns the subtlety of diplomacy and

martial arts.

Many immigrants lived in the Xiongnu pasturelands, but at first they did not mix with the Xiongnu. To be a Xiongnu, one had to be a member of a clan, born of Xiongnu parents. The newcomers were well off, but were outsiders, and could marry only among themselves, not the Xiongnu. Only later did they intermix, increase in numbers, even created a state that existed from 318 to 350 AD.

The Xiongnu culture can be differentiated into local, Scytho-Sarmatian, and Chinese. Most everyday objects were produced locally, showing the stability of the nomadic culture; Chinese masters made small handmade objects and ornaments; while objects with ideological connotations originated from the Scythian, Sarmatian and Dinlin S. Siberian cultures[2].

Among the most important artifacts from Noin-Ula are embroidered portrait images. These shed light on the ethnicity of the Xiongnu, albeit controversially. It has been claimed that the portraits depict Greco-Bactrians, or are Greek depictions of Scythian soldiers from the Black Sea. Such suggestions are far-fetched. There are several historical sources confirming the appearance of the Xiongnu. In 350 AD, for example, power in the South Xiongnu state of Chjao (Pin. Zhao) was seized by a usurper, a Chinese named Shi Min, who ordered all the Xiongnu in the state exterminated; in the slaughter "many Chinese with prominent noses" died, suggesting the Xiongnu had "prominent noses" compared to those of the Chinese. In the famous Chinese bas-relief "Fight on the bridge" the mounted Xiongnu are shown with big noses. A skull analysis of Xiongnu burials made by G.F. Debets found a distinct Paleo-Siberian type of Asian facial appearance with "not a flat, but with not strongly protruding nose", somewhat similar to some North American Indians. This type is represented on the embroidery from Noin-Ula. What to the rest of the Chinese looked like a high nose, to the Europeans looked like a flat nose.

The portraits are not made in the Chinese manner, and are the handiwork of a Central Asian or Scythian artist, or perhaps of a Bactrian or Parthian master in the capital of the Chanüys (who had active diplomatic relations with these Central Asian states).

The hairstyle on one portrait shows long hair bound with a wide ribbon. This is identical with the coiffure of the Türkic Ashina clan, who were originally from the Hesi province. The Ashina belonged to the last Xiongnu princedom destroyed by Xianbei-Toba by AD 439. From Gansu, the Ashina retreated to the Altai, taking with them a number of distinctive ethnographic traits.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Noin-Ula_kurgans

Many immigrants lived in the Xiongnu pasturelands, but at first they did not mix with the Xiongnu. To be a Xiongnu, one had to be a member of a clan, born of Xiongnu parents. The newcomers were well off, but were outsiders, and could marry only among themselves, not the Xiongnu. Only later did they intermix, increase in numbers, even created a state that existed from 318 to 350 AD.

The Xiongnu culture can be differentiated into local, Scytho-Sarmatian, and Chinese. Most everyday objects were produced locally, showing the stability of the nomadic culture; Chinese masters made small handmade objects and ornaments; while objects with ideological connotations originated from the Scythian, Sarmatian and Dinlin S. Siberian cultures[2].

Among the most important artifacts from Noin-Ula are embroidered portrait images. These shed light on the ethnicity of the Xiongnu, albeit controversially. It has been claimed that the portraits depict Greco-Bactrians, or are Greek depictions of Scythian soldiers from the Black Sea. Such suggestions are far-fetched. There are several historical sources confirming the appearance of the Xiongnu. In 350 AD, for example, power in the South Xiongnu state of Chjao (Pin. Zhao) was seized by a usurper, a Chinese named Shi Min, who ordered all the Xiongnu in the state exterminated; in the slaughter "many Chinese with prominent noses" died, suggesting the Xiongnu had "prominent noses" compared to those of the Chinese. In the famous Chinese bas-relief "Fight on the bridge" the mounted Xiongnu are shown with big noses. A skull analysis of Xiongnu burials made by G.F. Debets found a distinct Paleo-Siberian type of Asian facial appearance with "not a flat, but with not strongly protruding nose", somewhat similar to some North American Indians. This type is represented on the embroidery from Noin-Ula. What to the rest of the Chinese looked like a high nose, to the Europeans looked like a flat nose.

The portraits are not made in the Chinese manner, and are the handiwork of a Central Asian or Scythian artist, or perhaps of a Bactrian or Parthian master in the capital of the Chanüys (who had active diplomatic relations with these Central Asian states).

The hairstyle on one portrait shows long hair bound with a wide ribbon. This is identical with the coiffure of the Türkic Ashina clan, who were originally from the Hesi province. The Ashina belonged to the last Xiongnu princedom destroyed by Xianbei-Toba by AD 439. From Gansu, the Ashina retreated to the Altai, taking with them a number of distinctive ethnographic traits.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Noin-Ula_kurgans

The 10th-century Irk Bitig or "Book of Divination" of Dunhuang is an important source for early Turkic mythology The mythologies of the Turkic and Mongolian peoples (both groups speakers of Altaic languages) are related and have exerted strong influence on one another. Both groups of peoples qualify as Eurasian nomads and have been in close contact throughout history, especially in the context of the medieval Turco-Mongol empire.

The oldest mythological concept that can be reconstructed with any certainty is the sky god Tengri, attested from the Xiong Nu in the 2nd century BC.

Geser (Ges'r, Kesar) is a Mongolian religious epic about Geser (also known as Bukhe Beligte), prophet of Tengriism.

Mongolian Bai-Ulgan and Esege Malan are creator deities. Ot is the goddess of marriage. Tung-ak is the patron god of tribal chiefs. The Uliger are traditional epic tales and the Epic of King Gesar is shared with much of Central Asia and Tibet. Erlig Khan (Erlik Khan) is the King of the Underworld. Daichin Tengri is the red god of war to whom enemy soldiers were sometimes sacrificed during battle campaigns. Zaarin Tengri is a spirit who gives Khorchi (in the Secret History of the Mongols) a vision of a cow mooing "Heaven and earth have agreed to make Temujin (later Genghis Khan) the lord of the nation". The wolf, falcon, deer and horse were important symbolic animals.

There are many different Mongolian creation myths. In one, the creation of the world is attributed to a Lama. In the beginning there was only water, and from the heavens Lama came down to it holding an iron rod from which he began to stir the water. The stirring brought about a wind and fire which caused a thickening at the center of the waters to form earth.[1] Another narrative also attributes the creation of heaven and earth to a lama who is called Udan. Udan began by separating earth from heaven, and then dividing heaven and earth both into nine stories, and creating nine rivers. After the creation of the earth itself, the first male and female couple were created out of clay. They would become the progenitors of all humanity.[2]

In another example the world began as an agitating gas which grew increasingly warm and damp, precipitating a heavy rain that created the oceans. Dust and sand emerged to the surface and became earth.[2] Yet another account tells of the Buddha Sakyamuni searching the surface of the sea for a means to create the earth and spotted a golden frog. From its east side, Buddha pierced the frog through, causing it to spin and face north. From its mouth burst fire and from its rump streamed water. Buddha tossed golden sand on his back which became land. And this was the origin of the five earthly elements, wood and metal from the arrow, and fire, water and sand.[2] These myths date from the 17th century when Yellow Shamanism (Tibetan Buddhism using shamanistic forms) was established in Mongolia. Black Shamanism and White Shamanism from pre-Buddhist times survives only in far-northern Mongolia (around Lake Khuvsgul) and the region around Lake Baikal where Lamaist persecution had not been effective.

[edit] Turkic The Wolf symbolizes honour and is also considered the mother of most Turkic peoples. Asena (Ashina Tuwu) is the wolf mother of Bumen, the first Khan of the Göktürks.

The Horse is also one of the main figures of Turkic mythology; Turks considered the horse an extension of the individual -though generally dedicated to the male- and see that one is complete with it. This might have led to or sourced from the term "At-Beyi" (Horse-Lord).

The Dragon (Evren), also expressed as a Snake or Lizard, is the symbol of might and power. It is believed, especially in mountainous Central Asia, that dragons still live in the mountains of Tian Shan/Tengri Tagh and Altay. Dragons also symbolize the god Tengri (Tanrı) in ancient Turkic tradition, although dragons themselves are not worshipped as gods.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mythology_of_the_Turkic_and_Mongolian_peoples

The Uyghur Empire stretched its powerful arms from the Pacific Ocean

across Central Asia and into Eastren Europe from the Caspian Sea on.

This was before the British Isles became separated from the continent of

Europe.

The southern boundary of the Uyghur Empire was along the northern boundaries of Cochin China, Burma, India, and Persia,and this was before the Himalayas and the other Asiatic mountains were raised.

Their northern boundary extended into Siberia, but how far there is no record to tell. Remains of their cities have been found in the southern parts of Siberia.

Legendary history states that the Uyghurs extended themselves all through the central parts of Europe. The Book of Manu, an ancient Hindu book, says: " The Uyghurs had a settlement on the northern and eastern shores of the Caspian sea."

They settled in northern Spain, northern France, and far down into the Balkan region. The late archeological discoveries in Moravia are Uyghur remains, and the evidences in which ethnologists have based their theories that man originated in Asia have been marks left by the advancing Uyghurs in Europe.

Chinese legend tells that the Uyghurs were at the height of their civilization about 17,000 years ago. This date agrees with geological phenomenon.

An ancient record in a monastery states: "The capital City of the Uyghurs with all its people was destroyed by a flood which extended throughout the eastern part of the Empire, destroying all and everything." This ancient record is absolutely corroborated by geological phenomena.

At the time the Uyghur Empire was at its peak, the mountain had not been raised and what is now the Gobi Desert (Teklimakan)was a rich well-watered plain. Here the capital city of the Uyghurs was situated, almost due south from Lake Baikal. In 1896 a party of explorers, upon information received in Tibet, visited the site of the ancient city of Khara Khota. They had been told that the Uyghur capital city lay under the ruins of Khara Khota. They dug through these ruins and then through a stratum of boulders,gravel and sand fifty feet in thickness, and finally came upon the ruins of the capital city.

The history of the Uyghurs is the history of the Aryan races, for all of the true Aryan races descended from Uyghur forefathers. The Uyghurs formed chains of settlements across the central parts of Europe back in Tertiary Times. After the Empire was destroyed by the great magnetic cataclysm and mountain rising, the surviving remnants of humanity or their descendants again formed settlements in Europe. This was during the Pleistocene Time. The slaves, Tautens, Celts, Irish,Bretons and Basques are all descended from Uyghur stock. The Bretons,Basques, and genuine Irish are the descendants of those who survived the magnetic cataclysm and mountain raising.

Some Chinese records, bearing a date of 500 B.C. Describe the Uyghurs as having been "light-haired, blue-eyed people." " The Uyghurs were all of a light complexion, milk-white skin, with varying color of eyes and hair. In the north blue eye and light hair predominated. In the south were found those with dark hair and dark eyes."

The Uyghurs had reached a high state of civilization and culture.They knew astrology, mining, the textile industries,architecture, mathematics, agriculture, writing, reading, medicine, ect. They were experts in decorative art or silk, metals, and wood, and they made statues of gold, silver, bronze, and clay and this was before the history of Egypt commenced.

The history of Central Asia is the history of the Uyghurs. The Uyghur people are a distinct, vibrant cultural element of Central Asia. Whether you examine the role of Uyghur scholars in Genghis Khan's court as administrators, peruse the artistic wonders of their architectural accomplishments involving the Buddhist, Christian or Islamic periods, or read translations of the numerous written works on medicine,history or just their humor, one cannot but realize the unique and vital contributions of the Uyghur people to history.[Jack Churchward]

The southern boundary of the Uyghur Empire was along the northern boundaries of Cochin China, Burma, India, and Persia,and this was before the Himalayas and the other Asiatic mountains were raised.

Their northern boundary extended into Siberia, but how far there is no record to tell. Remains of their cities have been found in the southern parts of Siberia.

Legendary history states that the Uyghurs extended themselves all through the central parts of Europe. The Book of Manu, an ancient Hindu book, says: " The Uyghurs had a settlement on the northern and eastern shores of the Caspian sea."

They settled in northern Spain, northern France, and far down into the Balkan region. The late archeological discoveries in Moravia are Uyghur remains, and the evidences in which ethnologists have based their theories that man originated in Asia have been marks left by the advancing Uyghurs in Europe.

Chinese legend tells that the Uyghurs were at the height of their civilization about 17,000 years ago. This date agrees with geological phenomenon.

An ancient record in a monastery states: "The capital City of the Uyghurs with all its people was destroyed by a flood which extended throughout the eastern part of the Empire, destroying all and everything." This ancient record is absolutely corroborated by geological phenomena.

At the time the Uyghur Empire was at its peak, the mountain had not been raised and what is now the Gobi Desert (Teklimakan)was a rich well-watered plain. Here the capital city of the Uyghurs was situated, almost due south from Lake Baikal. In 1896 a party of explorers, upon information received in Tibet, visited the site of the ancient city of Khara Khota. They had been told that the Uyghur capital city lay under the ruins of Khara Khota. They dug through these ruins and then through a stratum of boulders,gravel and sand fifty feet in thickness, and finally came upon the ruins of the capital city.

The history of the Uyghurs is the history of the Aryan races, for all of the true Aryan races descended from Uyghur forefathers. The Uyghurs formed chains of settlements across the central parts of Europe back in Tertiary Times. After the Empire was destroyed by the great magnetic cataclysm and mountain rising, the surviving remnants of humanity or their descendants again formed settlements in Europe. This was during the Pleistocene Time. The slaves, Tautens, Celts, Irish,Bretons and Basques are all descended from Uyghur stock. The Bretons,Basques, and genuine Irish are the descendants of those who survived the magnetic cataclysm and mountain raising.

Some Chinese records, bearing a date of 500 B.C. Describe the Uyghurs as having been "light-haired, blue-eyed people." " The Uyghurs were all of a light complexion, milk-white skin, with varying color of eyes and hair. In the north blue eye and light hair predominated. In the south were found those with dark hair and dark eyes."

The Uyghurs had reached a high state of civilization and culture.They knew astrology, mining, the textile industries,architecture, mathematics, agriculture, writing, reading, medicine, ect. They were experts in decorative art or silk, metals, and wood, and they made statues of gold, silver, bronze, and clay and this was before the history of Egypt commenced.

The history of Central Asia is the history of the Uyghurs. The Uyghur people are a distinct, vibrant cultural element of Central Asia. Whether you examine the role of Uyghur scholars in Genghis Khan's court as administrators, peruse the artistic wonders of their architectural accomplishments involving the Buddhist, Christian or Islamic periods, or read translations of the numerous written works on medicine,history or just their humor, one cannot but realize the unique and vital contributions of the Uyghur people to history.[Jack Churchward]

The Xiongnu

The important early Chinese historian Sima Qian (145-90 BCE) gives us one of our earliest

glimpses into the lives and culture of the people known to the Han as the Xiongnu. In his

Shiji (Record of the Historian), he describes them as a pastoral nomadic people

wandering in search of grazing lands for their herds of horses, cows and sheep. He also

relates that the Xiongnu had no walled cities and did not engage in agriculture, and that

the men were formidable warriors, trained from an early age to hunt on horseback with bow

and arrow. Historical records also describe the Xiongnu as skilled charioteers, a

characterization supported by the discovery of bronze chariot post filials in archeological

excavations.

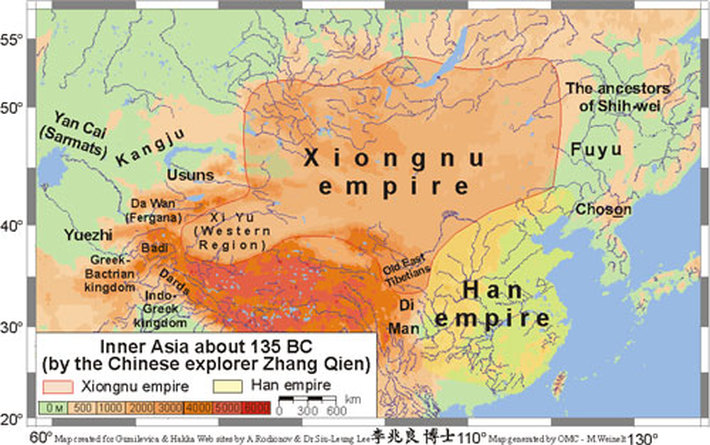

Originating in the northeastern Ordos region, the Xiongnu Empire was the first of its kind on the Eurasian steppe, and serves as a prototype of sorts for the many empires to follow, including that of the Mongols. The Ordos was an important gathering point for the various pastoral peoples of Inner Mongolia, and it is more accurate to describe the Xiongnu as a confederacy of these various groups rather than a single, unified culture. The founder of the Xiongnu confederation was Maodun, the son of a powerful and influential shanyu (high chieftain) among the nomads of the Ordos. After Maodun rose to the ranks of military commander he assassinated his father, and succeeded in unifying the various nomad groups under his leadership.

From 209 to 128 BCE the Xiongnu were at their most powerful. Under Maodun the confederacy established a firm power base in the Ordos, from where it began to expand in all directions. They retook the lands to the south lost to encroachment by the Qin dynasty, and absorbed the various smaller nomadic groups that roamed Inner Mongolia to the north. In the east they overwhelmed the Eastern Hu. In the west they defeated the Yuezhi (a rival coalition of nomadic peoples), driving them into Central Asia as far as northern Afghanistan. During this western campaign, the Xiongnu also took control over a number of oasis communities that had developed in the Tarim basin. The sub-commander in charge of overseeing these conquered city-states was given the title "general-in-charge-of-slaves"1, which tells us something about the Xiongnu's attitude towards those they conquered. From these agricultural communities they received grain, fruit, and animal feed, and from the nomads they enriched their herds of cattle, sheep, and most importantly, horses.

In 201 BCE, the first Han emperor Gaozu personally led his troops to the northern border in order to chastise a provincial governor who had declared independence. The governor had allied himself with the Xiongnu, and this first military encounter with the confederation of the steppes ended in humiliation for the Han. Unfamiliar with the attack-and-retreat strategy of the Xiongnu, Gaozu allowed himself to be separated from his main army, and was surrounded by the Xiongnu cavalry. Gaozu had no choice but to negotiate, and offered a settlement to win his own release.

Though the Han continued to hold the Xiongnu and their nomadic way of life in disdain ("xiongnu" is a Chinese word that translates roughly into "illegitimate offspring of slaves"), they could not ignore the very real military threat they posed to the Han Empire. To avert continued hostilities, the Han court was forced to maintain marital ties with the shanyu and offer annual tribute of silk, wines, rice and other foodstuffs.

Another Xiongnu demand that the Han were most loathe to recognize was the right to trade with Chinese communities at the frontier, for this would undermine the Han desire to keep a healthy buffer zone between the two empires. The Xiongnu countered this reluctance in the tried and true method: through raids, looting those goods that the Han court denied them purchase. Eventually the right to trade was granted, though the sale of arms and goods that could be used for military purposes was outlawed. This policy forced the Xiongnu to look to Central Asia for such as materials as iron, for which they traded many of the goods they had acquired from the Chinese. In this manner, Han trade policies with the Xiongnu were indirectly responsible for the increase in trade between East and Central Asia along the silk routes.

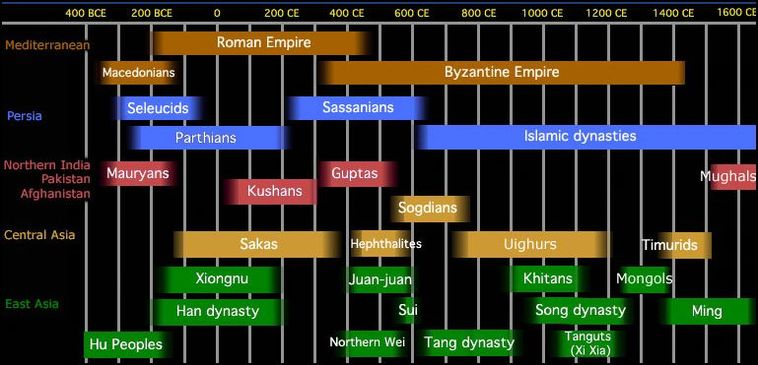

The Xiongnu was not only the first of the East Asian steppe empires; it was also the longest, lasting almost three hundred years. By 104 BCE the Han had reclaimed much of the northern territory they had lost a century earlier, and had driven the Xiongnu out of the west. They established military outposts as far west as Dunhuang to protect the city-states of the Tarim Basin from Xiongnu incursion, a position that also allowed them to enjoy the revenues generated by increased traffic along the trade routes. In 47 CE the Xiongnu split into northern and southern factions as a result of internal disputes. To protect themselves, the weaker Southerners asked for the protection of the Han Empire. Meanwhile, the northern Xiongnu suddenly found themselves threatened by the nomadic groups to the north, which they had previously dominated.

In 78 the Xianbei (ancestors of the Toba Wei, who would found the Wei dynasty three centuries later) attacked the northern Xiongnu. Seizing this opportunity, the Han court sent a force to join the southern Xiongnu faction to attack the Northerners. By 91 the northern Xiongnu were driven from the Ordos and fled west, their leadership dissipated.

(1) Ma Yong and Sun Yutan, "The Western Regions Under the Hsiung-nu and the Han," from History of Civilizations of Central Asia, vol. II (Paris: UNESCO Publishing), p. 228.

http://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/exhibit/xiongnu/xiongnu.html

Originating in the northeastern Ordos region, the Xiongnu Empire was the first of its kind on the Eurasian steppe, and serves as a prototype of sorts for the many empires to follow, including that of the Mongols. The Ordos was an important gathering point for the various pastoral peoples of Inner Mongolia, and it is more accurate to describe the Xiongnu as a confederacy of these various groups rather than a single, unified culture. The founder of the Xiongnu confederation was Maodun, the son of a powerful and influential shanyu (high chieftain) among the nomads of the Ordos. After Maodun rose to the ranks of military commander he assassinated his father, and succeeded in unifying the various nomad groups under his leadership.

From 209 to 128 BCE the Xiongnu were at their most powerful. Under Maodun the confederacy established a firm power base in the Ordos, from where it began to expand in all directions. They retook the lands to the south lost to encroachment by the Qin dynasty, and absorbed the various smaller nomadic groups that roamed Inner Mongolia to the north. In the east they overwhelmed the Eastern Hu. In the west they defeated the Yuezhi (a rival coalition of nomadic peoples), driving them into Central Asia as far as northern Afghanistan. During this western campaign, the Xiongnu also took control over a number of oasis communities that had developed in the Tarim basin. The sub-commander in charge of overseeing these conquered city-states was given the title "general-in-charge-of-slaves"1, which tells us something about the Xiongnu's attitude towards those they conquered. From these agricultural communities they received grain, fruit, and animal feed, and from the nomads they enriched their herds of cattle, sheep, and most importantly, horses.

In 201 BCE, the first Han emperor Gaozu personally led his troops to the northern border in order to chastise a provincial governor who had declared independence. The governor had allied himself with the Xiongnu, and this first military encounter with the confederation of the steppes ended in humiliation for the Han. Unfamiliar with the attack-and-retreat strategy of the Xiongnu, Gaozu allowed himself to be separated from his main army, and was surrounded by the Xiongnu cavalry. Gaozu had no choice but to negotiate, and offered a settlement to win his own release.

Though the Han continued to hold the Xiongnu and their nomadic way of life in disdain ("xiongnu" is a Chinese word that translates roughly into "illegitimate offspring of slaves"), they could not ignore the very real military threat they posed to the Han Empire. To avert continued hostilities, the Han court was forced to maintain marital ties with the shanyu and offer annual tribute of silk, wines, rice and other foodstuffs.

Another Xiongnu demand that the Han were most loathe to recognize was the right to trade with Chinese communities at the frontier, for this would undermine the Han desire to keep a healthy buffer zone between the two empires. The Xiongnu countered this reluctance in the tried and true method: through raids, looting those goods that the Han court denied them purchase. Eventually the right to trade was granted, though the sale of arms and goods that could be used for military purposes was outlawed. This policy forced the Xiongnu to look to Central Asia for such as materials as iron, for which they traded many of the goods they had acquired from the Chinese. In this manner, Han trade policies with the Xiongnu were indirectly responsible for the increase in trade between East and Central Asia along the silk routes.

The Xiongnu was not only the first of the East Asian steppe empires; it was also the longest, lasting almost three hundred years. By 104 BCE the Han had reclaimed much of the northern territory they had lost a century earlier, and had driven the Xiongnu out of the west. They established military outposts as far west as Dunhuang to protect the city-states of the Tarim Basin from Xiongnu incursion, a position that also allowed them to enjoy the revenues generated by increased traffic along the trade routes. In 47 CE the Xiongnu split into northern and southern factions as a result of internal disputes. To protect themselves, the weaker Southerners asked for the protection of the Han Empire. Meanwhile, the northern Xiongnu suddenly found themselves threatened by the nomadic groups to the north, which they had previously dominated.

In 78 the Xianbei (ancestors of the Toba Wei, who would found the Wei dynasty three centuries later) attacked the northern Xiongnu. Seizing this opportunity, the Han court sent a force to join the southern Xiongnu faction to attack the Northerners. By 91 the northern Xiongnu were driven from the Ordos and fled west, their leadership dissipated.

(1) Ma Yong and Sun Yutan, "The Western Regions Under the Hsiung-nu and the Han," from History of Civilizations of Central Asia, vol. II (Paris: UNESCO Publishing), p. 228.

http://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/exhibit/xiongnu/xiongnu.html

Xiongnu tomb excavation

http://www.silkroadfoundation.org/excavation/takhilt2007.html

http://www.silkroadfoundation.org/excavation/takhilt2007.html

The Noin-Ula kurgans

consist of more than 200 large burial mounds, approximately square in

plan, some 2 m in height, covering timber burial chambers. They are

located by the Selenga River in the hills of northern Mongolia north of Ulan Bator. They were excavated in 1924-1925 by Pyotr Kozlov, who found them to be the tombs of the aristocracy of the Xiongnu;

one is an exceptionally rich burial of a historically-known ruler of

the Xiongnu, Uchjulü-Jodi-Chanuy, who died in 13 CE. Most of the objects

from Noin-Ula are now in the Hermitage Museum, while some artifacts unearthed later by Mongolian archaeologists are on display in the National Museum of Mongolian History, Ulan Bator.

Two kurgans contained lacquer cups, inscribed with the name of their

Chinese maker and the date September 5 year of Tsian-ping era, i.e. 2nd

year BCE. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Noin-Ula_kurgans

Khar Balgas (Uighur)

Named Ordobalik in the Uighur language, the remains of this capital are situated at the confluence of the Orkhon and Jirmentei rivers in Arkhangai aimagand measures approximately 25 km2. Within the walls are the remnants of market places, workshops, temples and a royal residence enclosure with guard towers measuring 12m high and 600m2. Recent surveys and excavations of the joint Mongol-Chinese project headed by the National Museum of Mongolian History and the Inner Mongolia Archaeological Research Institute of China have mapped numerous Uighur square ritual and burial sites throughout the area (Ochir et al. 2005) and uncovered a ramped, round brick chamber tomb beneath one of these monuments during summer 2006.

Khar Khorin (Mongol)

The remains of this capital of the Mongol Empire, established in 1220, lie just north of the present-day Erdene-Zuu monestary in the Orkhon Valley. Recent excavations of this site by the Bonn University and Institute of Archaeology joint project have continued work at the palace structure of Ogedei Khaan as well as investigations of paved roads, kilns for ceramics production, and temples.

Ongot (Turk)

Close to the city of Ulaanbaatar lies a sacrificial site in the vicinity of a Turkish royal burial. A four-sided cyst of stone slabs carved with lattice decoration stands at the head of a long line of more than 550 standing stones stretching eastward, including 30 human and animal statuettes placed close to the cyst.

Named Ordobalik in the Uighur language, the remains of this capital are situated at the confluence of the Orkhon and Jirmentei rivers in Arkhangai aimagand measures approximately 25 km2. Within the walls are the remnants of market places, workshops, temples and a royal residence enclosure with guard towers measuring 12m high and 600m2. Recent surveys and excavations of the joint Mongol-Chinese project headed by the National Museum of Mongolian History and the Inner Mongolia Archaeological Research Institute of China have mapped numerous Uighur square ritual and burial sites throughout the area (Ochir et al. 2005) and uncovered a ramped, round brick chamber tomb beneath one of these monuments during summer 2006.

Khar Khorin (Mongol)

The remains of this capital of the Mongol Empire, established in 1220, lie just north of the present-day Erdene-Zuu monestary in the Orkhon Valley. Recent excavations of this site by the Bonn University and Institute of Archaeology joint project have continued work at the palace structure of Ogedei Khaan as well as investigations of paved roads, kilns for ceramics production, and temples.

Ongot (Turk)

Close to the city of Ulaanbaatar lies a sacrificial site in the vicinity of a Turkish royal burial. A four-sided cyst of stone slabs carved with lattice decoration stands at the head of a long line of more than 550 standing stones stretching eastward, including 30 human and animal statuettes placed close to the cyst.

http://www.ecogeodb.com/ECO_Detail.asp?P=History&CN=Kyrgyzstan&C=KGZ

NEW FACTIONS the Asian Barbarians after HUNS the Childerens of HUNS ::

Research and debate about the Asian ancestral origins of the Huns has been ongoing since the 18th century. For example philologists still debate to this day which ethnonym from Chinese or Persian sources is identical with the Latin Hunni or the Greek Hounnoi as evidence of the Huns' identity.

The most recent genetic and ethnogenesis based scholarship shows that many of the great confederations of steppe warriors were not entirely of the same race, but rather tended to be ethnic mixtures of Eurasian clans. In addition, many clans may have claimed to be Huns simply based on the prestige and fame of the name, or it was attributed to them by outsiders describing their common characteristics, believed place of origin, or reputation. Similarly, Greek or Latin chroniclers may have used "Huns" in a more general sense, to describe social or ethnic characteristics, believed place of origin, or reputation. "All we can say safely", says Walter Pohl,"is that the name Huns, in late antiquity, described prestigious ruling groups of steppe warriors".

The older views come in the context of the ethnocentric and nationalistic scholarship of past generations, which often presumed that ethnic homogeneity must underlie a socially and culturally homogeneous people. The modern research shows that each of the large confederations of steppe warriors (such as the Scythians, Xiongnu, Huns, Avars, Khazars, Cumans, Mongols, etc.) were not ethnically homogeneous, but rather unions of multiple ethnicities such as Turkic, Yeniseian, Tungusic, Ugric, Iranic, Mongolic and many other peoples.

The Xiongnu (Turkish: Doğu Hun; Chinese: pinyin: Xiōngnú; Wade-Giles: Hsiung-nu) were a confederation of nomadic tribes from Central Asia with a ruling class of unknown origin and other subjugated tribes. There is still a debate over the accurate order of command among the tribes, some sources say the ruling class was proto-Turkic, some others stand it was proto-Hunnic (see below), but the theories are far from universal acceptance in the academic world (like in the case of their language).

What is known that the confederation may consisted of proto-Huns, proto-Turkic clans and other nomadic tribes such as the proto-Mongols, and more others (some sources claim the existence of 24 clans), who lived on the steppes north of China. They appear in Chinese sources from the 3rd century BC as controlling an empire (the "Asian Hun Empire" (Turkish: Asya Hun İmparatorluğu) under Modu Shanyu) stretching beyond the borders of modern day Mongolia. They were active in the areas of southern Siberia, western Manchuria and the modern Chinese provinces of Inner Mongolia, Gansu, and Xinjiang. These nomadic people were considered so dangerous that the Qin Dynasty ordered the construction of the Great Wall to protect China from Xiongnu attacks.

The bulk of information on the Xiongnu comes from Chinese sources. What little is known of their titles and names comes from transliterations of Chinese character phoneticizations of their language. Only about 20 Xiongnu words belonging to the Altaic languages are known, and only a single Xiongnu sentence survives from the Chinese documents. Relations between early Chinese dynasties and the Xiongnu were complicated and included military conflict, exchanges of tribute and trade, and marriage treaties.

Xiongnu (Hsiung-nu) were led by a chief called shan-yü, whose full title transcribed into Chinese is Ch'eng-li Ku-t'u Shan-yü, words which the Chinese translate as "Majesty Son of Heaven". In these words may be detected Turko-Mongol roots: ch'eng-li in particular is the transcription of the Turkic and Mongol word Tängri, Heaven or God.

Under the shan-yü served "two great dignitaries, the kings t'u-ch'i": that is to say, the wise kings of the right and left, the Chinese transcription t'u-ch'i being related to the Turkish word doghri, straight, faithful. Insofar as one can speak of fixed dwellings for essentially nomadic people, the shan-yü resided on the upper Orkhon, in the mountainous region where later Karakorum, the capital of the Jengiz-Khanite Mongols, was to be established.

The worthy king of the left -in principle, the heir presumptive- lived in the east, probably on the high Kerulen. The worthy king of the right lived in the west, perhaps near present day Uliassutai in the Khangai Mountains. Next, moving down the scale of the Hunnic hierarchy, came the ku-li "kings" of left and right, the army commanders of left and right, the great governors, the tung-hu, the ku-tu-all of left and right; then the chiefs of a thousand men, of a hundred, and of ten men. This nation of nomads, a people on the march, was organized like an army. The general orientation was southward, as was customary among Turko-Mongol peoples; the same phenomenon is to be seen among the descendants of the Hsiung-nu, the Turks of the sixth century A.D., as well as in the case of the Mongols of Jenghiz Khan.

Touman (Turkish: Teoman, Tuman) was the earliest known Hiungnu (Xiongnu) chanyu, reigning from 220 BC to 209 BC.

He reformed the Hunnic nomad military system, formed the army unit of 10000 men: Tumen. This later became the base unit of the armies of steppe tribes. During his reign, he united the nomadic tribes living in Mongolia and invaded Northern China.

With this new military, his son Mao-Tun (Mete Han) could establish the Asian Hun Empire.

Many Turkish historians consider Teoman to be the founder of the first proto-Turkic state preceding the division of the Huns, the Turks, the Mongols, and other Altaic and Uralic peoples.

His name's meaning is straight, raw, packed and hard smoke in old Hunnic.

Modun Shanyu (Baatur, Bator, Baghadur, Bahadır) (born 234 BC) was the founder of the Asian Hun Empire (Xiongnu Empire), in 209 BC. According to Chinese records, the name is Modu. The beginning of his rule is also accepted as the formation of the first systematic nomad army. The years of his rule were 209 BCE to 174 BCE.

He was a military leader under his father Touman, and later the Shanyu and emperor of the Xiongnu Empire, located in modern day Mongolia. He made many conquests in Central Asia, before Turkic Göktürks,Genghis Khan and the Mongol conquests.

The word "Baatur" (Batur, Bator) means brave, courageous, in old Hunnic, Mongolian, Turkic languages and Hungarian language. Baghadur (Baghatur): hadur means warlord in Hungarian. So his name approximately could be translated to meaning Brave Warlord.

the Gokturks

The 'Gök Türkler were a Turkic people of ancient Central Asia. Known in medieval Chinese sources as T'u küe (Tūjué), the Gök türkler under the leadership of Bumin Khan (d. 552) and his sons succeeded the Xiongnu as the main Turkic power in the region and took hold of the lucrative Silk Road trade.

The Gök türk rulers originated from the Ashina tribe, an Altaic people who lived in the northern corner of the area presently called Xinjiang. Under their leadership, the Göktürkler rapidly expanded to rule huge territories in north-western China, North Asia and Eastern Europe (as far west as the Crimea). They were the first Turkic tribe known to use the name "Turk" as a political name.

The state's most famous personalities other than its founder Bumin were princes Kül Tigin and Bilge and the General Tonyukuk, whose life stories were recorded in the famous Orkhon inscriptions.

Göktürk Empire split in two after the death of the fourth Qaghan, Taspar Khan (ca. 584). He had willed the title Qaghan to Mukhan's son Talopien, but the high council appointed Ishbara in his stead, Western and Eastern

The Western Turkic Khaganate was formed as a result of the internecine wars in the beginning of the 7th century (600 – 603 AD) after the Göktürk Khaganate (founded in the 6th century in Northern Mongolia by the Ashina clan) had splintered into two polities – Eastern and Western.

The Western Turks (also known as the Onoq, or "ten arrows") sought friendly relations with the Byzantine Empire in order to expand their territory at the expense of their mutual enemy, the Sassanid Empire. In 619 the Western Turks invaded Bactria but were repulsed in the course of the Second Perso-Turkic War. During the Third Perso-Turkic War Khagan Tung Yabghu and his nephew Buri-sad joined their forces with Emperor Heraclius and successfully invaded Transcaucasia.

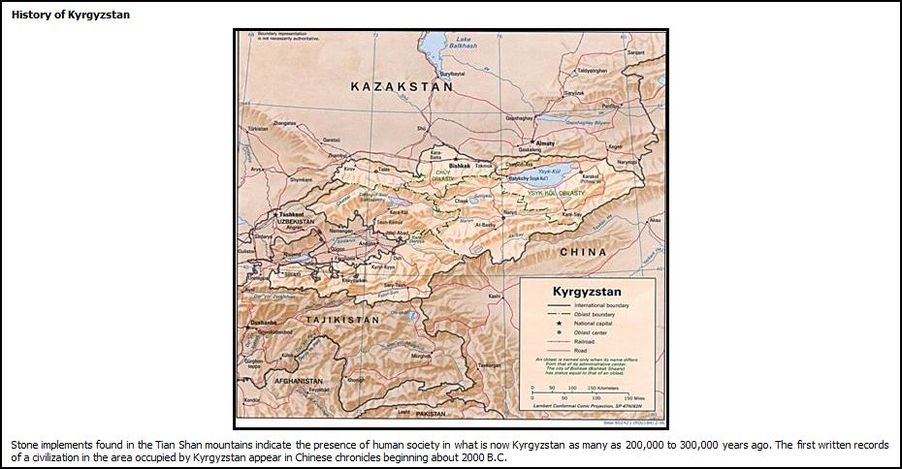

The khaganate's capitals were Navekat (the summer capital) and Suyab (the principal capital), both situated in the Chui River valley of Kyrgyzstan, to the east from Bishkek. The khaganate was overrun by Chinese forces under Su Dingfang in 658-659.

Qilibi Khan (d. 645?), personal name Ashina Simo, also known as Li Simo, full regal title Yiminishuqilibi Khan, Tang noble title Prince of Huaihua, was a member of the Eastern Tujue (Göktürk) royal house who was given the title of Khan of Eastern Tujue for several years, as a vassal of the Chinese dynasty Tang Dynasty.

After Emperor Taizong of Tang conquered Eastern Tujue in 630, he briefly settled the Eastern Tujue people within Tang borders, but after a failed assassination attempt against him by a member of the Eastern Tujue royal house, Ashina Jiesheshuai, in 639, he changed his mind and decided to resettle the Eastern Tujue people between the Great Wall and the Gobi Desert, to serve as a buffer between Tang and Xueyantuo. He created Ashina Simo, a member of Eastern Tujue's royal house as well, as Yiminishuqilibi Khan (or Qilibi Khan for short), and Ashina Simo served as the khan of the recreated Eastern Tujue khanate for several years. However, in 644, faced with constant pressure from Xueyantuo, Ashina Simo's people abandoned him and fled south back to Tang territory. Ashina Simo himself also returned to Tang and served as a Tang general until his death, probably in 645.

Despite all the setbacks, Ilteriş Şad (Idat) and his brother Bäkçor Qapağan Khan (Mo-ch'o) succeeded in reestablishing the Khanate. In 681 they revolted against Tang Dynasty Chinese domination and, over the following decades, steadily gained control of the steppes beyond the Great Wall of China. By 705, they had expanded as far south as Samarkand and threatened the Arab control of Transoxiana. The Göktürks clashed with the Umayyad Califate in a series of battles (712-713) but, again, the Arabs emerged as victors.

Following the Ashina tradition, the power of the Second Empire was centered on Ötükän (the upper reaches of the Orkhon River). This polity was described by historians as "the joint enterprise of the Ashina clan and the Soghdians, with large numbers of Chinese bureaucrats being involved as well". The son of Ilteriş, Bilge, was also a strong leader, the one whose deeds were recorded in the Orkhon inscriptions. After his death in 734 the empire declined. The Göktürks ultimately fell victim to a series of internal crises and renewed Chinese campaigns.

When Kutluk Khan of the Uyghurs allied himself with the Karluks and Basmyls, the power of the Göktürks was very much on the wane. In 744 Kutluk seized Ötükän and beheaded the last Göktürk khagan Özmish Khan, whose head was sent to the Tang Dynasty Chinese court. In a space of few years, the Uyghurs gained mastery of Inner Asia and established the Uyghur Khaganate.

the Avars

The Avars were a highly organized and powerful multi-ethnic tribal confederation, with a Turkic core of aristocratic nomads, governed by a central ruler (khagan). They appeared in Central and Eastern Europe in the 6th century. Avar rule persisted over much of the Pannonian plain up to the early 9th century.

The origin of the European Avars is unclear. Information is derived primarily from the works of Byzantine historians Menander Protector and Theophylact Simocatta. The confusion is compounded by the fact that many clans carried a particular name because they believed it to be prestigious, or it was attributed to them by outsiders describing their common characteristics, believed place of origin or reputation. Such a case has been seen repeatedly for many nomadic confederacies.

According to the research of historian András Róna-Tas, the Avars formed in central Asia through a fusion of several tribal elements, in the classical age. Rona-Tas suggests that Turkic Oghurs migrated to the Kazakh steppe, possibly moving south to inhabit the lands vacated by the Huns. Here they interacted with a body Indo-European-speaking Iranians – forming the Xionites (Hunas). Sometime during the 460s, they were subordinated by the Mongolic Ruanruan. The Ruanruan imposed their own rulers– referred to as Uar -at the head of the confederacy. Being a highly cultured people, the Ughurs rose to prominence within the tribal confederacy. The 6th century historian Menander Protector noted that the language of the Avars was the same (possibly meaning similar) as that of the Huns. If language is an indicator of origin, this supports the theory that they might have been an Oghuric Turkic people. The connection with the Rouran has prompted some scholars to suggest that the European Avars’ ruling core was Mongolic, although this has been disputed by others.

Early in the sixth century, the confederacy was conquered by the Gokturk empire (the Gokturks were previously yet another vassal tribal element under Ruanruan supremacy). In his History of the World, Theophylact Simocatta noted that the (Gok)Turks “enslaved the entire Ohgur tribe, which was one of the most powerful, .. and was accomplished in the art of war”. One body of people, perhaps wishing to evade Gokturk rule, escaped and migrated to the northern Caucasus region c. 555 AD. According to Simocatta, their new neighbours believed them to be the true Avars. They established diplomatic contact with the Byzantines, and the other nomadic tribes of the steppes lavished them with gifts. However, the Gokturks later persuaded the Byzantines that these nomads were not the real Avars, but were instead a group of "fugitive Scythians" who had fled from the Gokturks and stolen the prestigious name of Avar. Hence they have subsequebtly called pseudo-Avars (or Eurasian Avars).

For all the theories, historian Walter Pohl asserted in 1998, instancing the detailed attempts made by H. W. Haussig in 1953 and K. Czeglèdy in 1983 and his own methodological objections:"It is pointless to ask who exactly the forefathers of the European Avars were. We only know that they carried an ancient, very prestigious name (our first hints to it date back to the times of Herodotus); and we may assume that they were a very mixed group of warriors who wanted to escape domination by the Gokturks." If the Avars were ever a distinct ethnic group, that distinction does not seem to have survived their centuries in Europe. Being an 'Avar' seems to have meant being part of the Avar state (in a similar way that being 'Roman' ceased to have any ethnic meaning).What is certain, by the time they arrived in Europe, the Avars were a heterogeneous, polyethnic people. Modern research shows that each of the large confederations of steppe warriors (such as the Scythians, Xiongnu, Huns, Avars, Khazars, Cumans, Mongols, etc.) were not ethnically homogeneous, but rather unions of multiple ethnicities. The skeletons found in European Avar graves show heterogeneity, including some Asiatic features.

the Khazars

The Khazars were a semi-nomadic Turkic people who dominated the Pontic steppe and the North Caucasus from the 7th to the 10th century CE. The name 'Khazar' seems to be tied to a Turkic verb form meaning "wandering".

In the 7th century CE, the Khazars founded an independent Khaganate in the Northern Caucasus along the Caspian Sea. Although the Khazars were initially Tengri shamanists, many of them converted to Christianity, Islam, and other religions. During the eighth or ninth century the state religion became Judaism. At their height, the Khazar khaganate and its tributaries controlled much of what is today southern Russia, western Kazakhstan, eastern Ukraine, Azerbaijan, large portions of the Caucasus (including Circassia, Dagestan, Chechnya, and parts of Georgia), and the Crimea.

Between 965 and 969, their sovereignty was broken by Sviatoslav I of Kiev, and they became a subject people of Kievan Rus'. Gradually displaced by the Rus, the Kipchaks, and later the conquering Mongol Golden Horde, the Khazars largely disappeared as a culturally-distinct people.

the Bulgars

The Dulo Clan or the House of Dulo was the name of the ruling dynasty of the early Bulgars.

This was the clan of Kubrat who founded the Onogur state of Bulgars and Avars, also known as the Old Great Bulgaria, and his sons Batbayan, Kuber and Asparuh, the latter of which founded Danube Bulgaria.

A later genealogy claims that the Dulo clan is descended from Attila the Hun. It is also likely that they were somewhat related to the Ashina clan, though it seems that Dulo not only broke off from the royal Ashina clan, but was totally opposed to it, manifesting it not only in opposition to the Khazar Kaganate headed by an Ashina kagan, but also demonstratively not using the name. The Dulo clan name descends from the Dulo (Tele) tribe group, and the Dulo/Ashina opposition was a main cause of the ethnic conflicts that tore apart the Turkic Kaganate, and a little later the Western Turkic Kaganate, bringing about the short-lived independence of the Great Bulgaria, and the emergence of Danube Bulgaria and Rus kaganate in the early 800 CE.

http://www.twcenter.net/forums/showthread.php?t=190564

Research and debate about the Asian ancestral origins of the Huns has been ongoing since the 18th century. For example philologists still debate to this day which ethnonym from Chinese or Persian sources is identical with the Latin Hunni or the Greek Hounnoi as evidence of the Huns' identity.

The most recent genetic and ethnogenesis based scholarship shows that many of the great confederations of steppe warriors were not entirely of the same race, but rather tended to be ethnic mixtures of Eurasian clans. In addition, many clans may have claimed to be Huns simply based on the prestige and fame of the name, or it was attributed to them by outsiders describing their common characteristics, believed place of origin, or reputation. Similarly, Greek or Latin chroniclers may have used "Huns" in a more general sense, to describe social or ethnic characteristics, believed place of origin, or reputation. "All we can say safely", says Walter Pohl,"is that the name Huns, in late antiquity, described prestigious ruling groups of steppe warriors".

The older views come in the context of the ethnocentric and nationalistic scholarship of past generations, which often presumed that ethnic homogeneity must underlie a socially and culturally homogeneous people. The modern research shows that each of the large confederations of steppe warriors (such as the Scythians, Xiongnu, Huns, Avars, Khazars, Cumans, Mongols, etc.) were not ethnically homogeneous, but rather unions of multiple ethnicities such as Turkic, Yeniseian, Tungusic, Ugric, Iranic, Mongolic and many other peoples.

The Xiongnu (Turkish: Doğu Hun; Chinese: pinyin: Xiōngnú; Wade-Giles: Hsiung-nu) were a confederation of nomadic tribes from Central Asia with a ruling class of unknown origin and other subjugated tribes. There is still a debate over the accurate order of command among the tribes, some sources say the ruling class was proto-Turkic, some others stand it was proto-Hunnic (see below), but the theories are far from universal acceptance in the academic world (like in the case of their language).

What is known that the confederation may consisted of proto-Huns, proto-Turkic clans and other nomadic tribes such as the proto-Mongols, and more others (some sources claim the existence of 24 clans), who lived on the steppes north of China. They appear in Chinese sources from the 3rd century BC as controlling an empire (the "Asian Hun Empire" (Turkish: Asya Hun İmparatorluğu) under Modu Shanyu) stretching beyond the borders of modern day Mongolia. They were active in the areas of southern Siberia, western Manchuria and the modern Chinese provinces of Inner Mongolia, Gansu, and Xinjiang. These nomadic people were considered so dangerous that the Qin Dynasty ordered the construction of the Great Wall to protect China from Xiongnu attacks.

The bulk of information on the Xiongnu comes from Chinese sources. What little is known of their titles and names comes from transliterations of Chinese character phoneticizations of their language. Only about 20 Xiongnu words belonging to the Altaic languages are known, and only a single Xiongnu sentence survives from the Chinese documents. Relations between early Chinese dynasties and the Xiongnu were complicated and included military conflict, exchanges of tribute and trade, and marriage treaties.

Xiongnu (Hsiung-nu) were led by a chief called shan-yü, whose full title transcribed into Chinese is Ch'eng-li Ku-t'u Shan-yü, words which the Chinese translate as "Majesty Son of Heaven". In these words may be detected Turko-Mongol roots: ch'eng-li in particular is the transcription of the Turkic and Mongol word Tängri, Heaven or God.

Under the shan-yü served "two great dignitaries, the kings t'u-ch'i": that is to say, the wise kings of the right and left, the Chinese transcription t'u-ch'i being related to the Turkish word doghri, straight, faithful. Insofar as one can speak of fixed dwellings for essentially nomadic people, the shan-yü resided on the upper Orkhon, in the mountainous region where later Karakorum, the capital of the Jengiz-Khanite Mongols, was to be established.

The worthy king of the left -in principle, the heir presumptive- lived in the east, probably on the high Kerulen. The worthy king of the right lived in the west, perhaps near present day Uliassutai in the Khangai Mountains. Next, moving down the scale of the Hunnic hierarchy, came the ku-li "kings" of left and right, the army commanders of left and right, the great governors, the tung-hu, the ku-tu-all of left and right; then the chiefs of a thousand men, of a hundred, and of ten men. This nation of nomads, a people on the march, was organized like an army. The general orientation was southward, as was customary among Turko-Mongol peoples; the same phenomenon is to be seen among the descendants of the Hsiung-nu, the Turks of the sixth century A.D., as well as in the case of the Mongols of Jenghiz Khan.

Touman (Turkish: Teoman, Tuman) was the earliest known Hiungnu (Xiongnu) chanyu, reigning from 220 BC to 209 BC.

He reformed the Hunnic nomad military system, formed the army unit of 10000 men: Tumen. This later became the base unit of the armies of steppe tribes. During his reign, he united the nomadic tribes living in Mongolia and invaded Northern China.

With this new military, his son Mao-Tun (Mete Han) could establish the Asian Hun Empire.

Many Turkish historians consider Teoman to be the founder of the first proto-Turkic state preceding the division of the Huns, the Turks, the Mongols, and other Altaic and Uralic peoples.

His name's meaning is straight, raw, packed and hard smoke in old Hunnic.

Modun Shanyu (Baatur, Bator, Baghadur, Bahadır) (born 234 BC) was the founder of the Asian Hun Empire (Xiongnu Empire), in 209 BC. According to Chinese records, the name is Modu. The beginning of his rule is also accepted as the formation of the first systematic nomad army. The years of his rule were 209 BCE to 174 BCE.

He was a military leader under his father Touman, and later the Shanyu and emperor of the Xiongnu Empire, located in modern day Mongolia. He made many conquests in Central Asia, before Turkic Göktürks,Genghis Khan and the Mongol conquests.

The word "Baatur" (Batur, Bator) means brave, courageous, in old Hunnic, Mongolian, Turkic languages and Hungarian language. Baghadur (Baghatur): hadur means warlord in Hungarian. So his name approximately could be translated to meaning Brave Warlord.

the Gokturks

The 'Gök Türkler were a Turkic people of ancient Central Asia. Known in medieval Chinese sources as T'u küe (Tūjué), the Gök türkler under the leadership of Bumin Khan (d. 552) and his sons succeeded the Xiongnu as the main Turkic power in the region and took hold of the lucrative Silk Road trade.

The Gök türk rulers originated from the Ashina tribe, an Altaic people who lived in the northern corner of the area presently called Xinjiang. Under their leadership, the Göktürkler rapidly expanded to rule huge territories in north-western China, North Asia and Eastern Europe (as far west as the Crimea). They were the first Turkic tribe known to use the name "Turk" as a political name.

The state's most famous personalities other than its founder Bumin were princes Kül Tigin and Bilge and the General Tonyukuk, whose life stories were recorded in the famous Orkhon inscriptions.

Göktürk Empire split in two after the death of the fourth Qaghan, Taspar Khan (ca. 584). He had willed the title Qaghan to Mukhan's son Talopien, but the high council appointed Ishbara in his stead, Western and Eastern

The Western Turkic Khaganate was formed as a result of the internecine wars in the beginning of the 7th century (600 – 603 AD) after the Göktürk Khaganate (founded in the 6th century in Northern Mongolia by the Ashina clan) had splintered into two polities – Eastern and Western.

The Western Turks (also known as the Onoq, or "ten arrows") sought friendly relations with the Byzantine Empire in order to expand their territory at the expense of their mutual enemy, the Sassanid Empire. In 619 the Western Turks invaded Bactria but were repulsed in the course of the Second Perso-Turkic War. During the Third Perso-Turkic War Khagan Tung Yabghu and his nephew Buri-sad joined their forces with Emperor Heraclius and successfully invaded Transcaucasia.

The khaganate's capitals were Navekat (the summer capital) and Suyab (the principal capital), both situated in the Chui River valley of Kyrgyzstan, to the east from Bishkek. The khaganate was overrun by Chinese forces under Su Dingfang in 658-659.

Qilibi Khan (d. 645?), personal name Ashina Simo, also known as Li Simo, full regal title Yiminishuqilibi Khan, Tang noble title Prince of Huaihua, was a member of the Eastern Tujue (Göktürk) royal house who was given the title of Khan of Eastern Tujue for several years, as a vassal of the Chinese dynasty Tang Dynasty.

After Emperor Taizong of Tang conquered Eastern Tujue in 630, he briefly settled the Eastern Tujue people within Tang borders, but after a failed assassination attempt against him by a member of the Eastern Tujue royal house, Ashina Jiesheshuai, in 639, he changed his mind and decided to resettle the Eastern Tujue people between the Great Wall and the Gobi Desert, to serve as a buffer between Tang and Xueyantuo. He created Ashina Simo, a member of Eastern Tujue's royal house as well, as Yiminishuqilibi Khan (or Qilibi Khan for short), and Ashina Simo served as the khan of the recreated Eastern Tujue khanate for several years. However, in 644, faced with constant pressure from Xueyantuo, Ashina Simo's people abandoned him and fled south back to Tang territory. Ashina Simo himself also returned to Tang and served as a Tang general until his death, probably in 645.

Despite all the setbacks, Ilteriş Şad (Idat) and his brother Bäkçor Qapağan Khan (Mo-ch'o) succeeded in reestablishing the Khanate. In 681 they revolted against Tang Dynasty Chinese domination and, over the following decades, steadily gained control of the steppes beyond the Great Wall of China. By 705, they had expanded as far south as Samarkand and threatened the Arab control of Transoxiana. The Göktürks clashed with the Umayyad Califate in a series of battles (712-713) but, again, the Arabs emerged as victors.

Following the Ashina tradition, the power of the Second Empire was centered on Ötükän (the upper reaches of the Orkhon River). This polity was described by historians as "the joint enterprise of the Ashina clan and the Soghdians, with large numbers of Chinese bureaucrats being involved as well". The son of Ilteriş, Bilge, was also a strong leader, the one whose deeds were recorded in the Orkhon inscriptions. After his death in 734 the empire declined. The Göktürks ultimately fell victim to a series of internal crises and renewed Chinese campaigns.

When Kutluk Khan of the Uyghurs allied himself with the Karluks and Basmyls, the power of the Göktürks was very much on the wane. In 744 Kutluk seized Ötükän and beheaded the last Göktürk khagan Özmish Khan, whose head was sent to the Tang Dynasty Chinese court. In a space of few years, the Uyghurs gained mastery of Inner Asia and established the Uyghur Khaganate.

the Avars

The Avars were a highly organized and powerful multi-ethnic tribal confederation, with a Turkic core of aristocratic nomads, governed by a central ruler (khagan). They appeared in Central and Eastern Europe in the 6th century. Avar rule persisted over much of the Pannonian plain up to the early 9th century.

The origin of the European Avars is unclear. Information is derived primarily from the works of Byzantine historians Menander Protector and Theophylact Simocatta. The confusion is compounded by the fact that many clans carried a particular name because they believed it to be prestigious, or it was attributed to them by outsiders describing their common characteristics, believed place of origin or reputation. Such a case has been seen repeatedly for many nomadic confederacies.

According to the research of historian András Róna-Tas, the Avars formed in central Asia through a fusion of several tribal elements, in the classical age. Rona-Tas suggests that Turkic Oghurs migrated to the Kazakh steppe, possibly moving south to inhabit the lands vacated by the Huns. Here they interacted with a body Indo-European-speaking Iranians – forming the Xionites (Hunas). Sometime during the 460s, they were subordinated by the Mongolic Ruanruan. The Ruanruan imposed their own rulers– referred to as Uar -at the head of the confederacy. Being a highly cultured people, the Ughurs rose to prominence within the tribal confederacy. The 6th century historian Menander Protector noted that the language of the Avars was the same (possibly meaning similar) as that of the Huns. If language is an indicator of origin, this supports the theory that they might have been an Oghuric Turkic people. The connection with the Rouran has prompted some scholars to suggest that the European Avars’ ruling core was Mongolic, although this has been disputed by others.

Early in the sixth century, the confederacy was conquered by the Gokturk empire (the Gokturks were previously yet another vassal tribal element under Ruanruan supremacy). In his History of the World, Theophylact Simocatta noted that the (Gok)Turks “enslaved the entire Ohgur tribe, which was one of the most powerful, .. and was accomplished in the art of war”. One body of people, perhaps wishing to evade Gokturk rule, escaped and migrated to the northern Caucasus region c. 555 AD. According to Simocatta, their new neighbours believed them to be the true Avars. They established diplomatic contact with the Byzantines, and the other nomadic tribes of the steppes lavished them with gifts. However, the Gokturks later persuaded the Byzantines that these nomads were not the real Avars, but were instead a group of "fugitive Scythians" who had fled from the Gokturks and stolen the prestigious name of Avar. Hence they have subsequebtly called pseudo-Avars (or Eurasian Avars).

For all the theories, historian Walter Pohl asserted in 1998, instancing the detailed attempts made by H. W. Haussig in 1953 and K. Czeglèdy in 1983 and his own methodological objections:"It is pointless to ask who exactly the forefathers of the European Avars were. We only know that they carried an ancient, very prestigious name (our first hints to it date back to the times of Herodotus); and we may assume that they were a very mixed group of warriors who wanted to escape domination by the Gokturks." If the Avars were ever a distinct ethnic group, that distinction does not seem to have survived their centuries in Europe. Being an 'Avar' seems to have meant being part of the Avar state (in a similar way that being 'Roman' ceased to have any ethnic meaning).What is certain, by the time they arrived in Europe, the Avars were a heterogeneous, polyethnic people. Modern research shows that each of the large confederations of steppe warriors (such as the Scythians, Xiongnu, Huns, Avars, Khazars, Cumans, Mongols, etc.) were not ethnically homogeneous, but rather unions of multiple ethnicities. The skeletons found in European Avar graves show heterogeneity, including some Asiatic features.

the Khazars

The Khazars were a semi-nomadic Turkic people who dominated the Pontic steppe and the North Caucasus from the 7th to the 10th century CE. The name 'Khazar' seems to be tied to a Turkic verb form meaning "wandering".

In the 7th century CE, the Khazars founded an independent Khaganate in the Northern Caucasus along the Caspian Sea. Although the Khazars were initially Tengri shamanists, many of them converted to Christianity, Islam, and other religions. During the eighth or ninth century the state religion became Judaism. At their height, the Khazar khaganate and its tributaries controlled much of what is today southern Russia, western Kazakhstan, eastern Ukraine, Azerbaijan, large portions of the Caucasus (including Circassia, Dagestan, Chechnya, and parts of Georgia), and the Crimea.

Between 965 and 969, their sovereignty was broken by Sviatoslav I of Kiev, and they became a subject people of Kievan Rus'. Gradually displaced by the Rus, the Kipchaks, and later the conquering Mongol Golden Horde, the Khazars largely disappeared as a culturally-distinct people.

the Bulgars

The Dulo Clan or the House of Dulo was the name of the ruling dynasty of the early Bulgars.

This was the clan of Kubrat who founded the Onogur state of Bulgars and Avars, also known as the Old Great Bulgaria, and his sons Batbayan, Kuber and Asparuh, the latter of which founded Danube Bulgaria.

A later genealogy claims that the Dulo clan is descended from Attila the Hun. It is also likely that they were somewhat related to the Ashina clan, though it seems that Dulo not only broke off from the royal Ashina clan, but was totally opposed to it, manifesting it not only in opposition to the Khazar Kaganate headed by an Ashina kagan, but also demonstratively not using the name. The Dulo clan name descends from the Dulo (Tele) tribe group, and the Dulo/Ashina opposition was a main cause of the ethnic conflicts that tore apart the Turkic Kaganate, and a little later the Western Turkic Kaganate, bringing about the short-lived independence of the Great Bulgaria, and the emergence of Danube Bulgaria and Rus kaganate in the early 800 CE.

http://www.twcenter.net/forums/showthread.php?t=190564

Yuezhi

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yuezhi

A dragon brother points out that, "Yuezhi are considered by some scholars to be the precursors of the White Huns, who formed the third and last definite layer in Pashtun ethnogenesis about 1500 years ago.

It was those Huns that, in turn gave rise to the Ashina, a later proto-Turkic form.

Our Pashto language is a Saka (Scythian) dialect, the closest living to any Scythian tongue. Tocharian, which became extinct about 1000 years ago, is thought to have added to it....

"Ashina" is derived from the Saka word for "Blue" which is "Asheen", since it referred to the Blue Turks, who were thus called because of the "Sky" connotation - as they were "Celestial" or holy, Turks......the word "Sheen/Shin" is still the Pashto word for blue.....so, the Ashina, it appears, have more than one Pashtun link. You would do well to note this piece about "shin/sheen = blue"

Some sources identify the Yuezhi with the ancient Tocharians.[14]

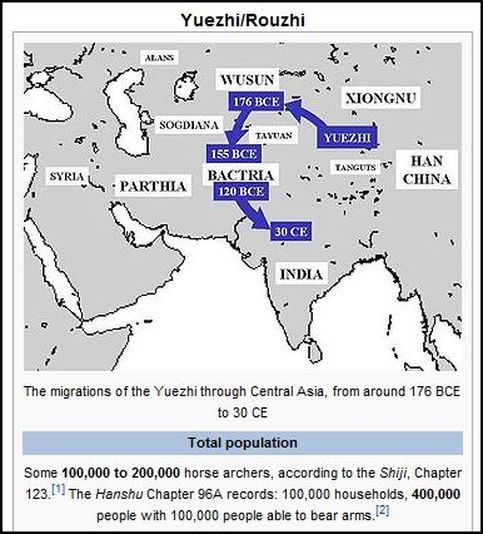

The Yuezhi, or Rouzhi (Chinese: 月支; pinyin: yuè zhī or ròu zhī; also Chinese: 月氏; pinyin: yuè shì or ròu shì; Old Chinese: Tokwar),[5]Da Yuezhi or Da Rouzhi (Chinese: 大月支, dà yuè zhī or dà ròu zhī, "Great Yuezhi"), were an ancient Central Asian people.

They are believed by most scholars to have been an Indo-European people[6] and may have been the same as or closely related to the Tocharians[7] (Τοχάριοι) of Classical sources.[8] They were originally settled in the arid grasslands of the eastern Tarim Basin area, in what is today Xinjiang and western Gansu, in China, before they migrated to Transoxiana, Bactria and then northern South Asia, where they may have had a part in forming the Kushan Empire.

also known as the people.

According to former USSR scholar Zuev, there was a queen among the large Yuezhi confederation who added to her possessions the lands of the Tochar (Pinyin: Daxia) on the headwaters of the Huanghe c. 3rd century BCE. According to Zuev, the Chinese chronicles began referring to the queen's tribe as the Great Yuezhi (Da Yuezhi) and to the Tochars as the Lesser Yuezhi (Pinyin: Xiao Yuezhi). Together, they were simply called Yuezhi. In the 5th century CE, scholar, translator and monk Kumarajiva, while translating texts into Chinese, used the name Yuezhi to translate Tochar. In the middle of the 2nd century BCE, the Yuezhi conquered Bactria, and the Ancient Greek authors inform us that the conquerors of Bactria were the Asii and Tochari tribes. In the Chinese chronicles Bactria then began to be called the country of Daxia, i.e., Tocharistan, and the language of Bactria/Tocharistan began to be called Tocharian.[17]

The Yuezhi are also documented in detail in Chinese historical accounts, in particular the 2nd-1st century BCE Records of the Great Historian, or Shiji, by Sima Qian. According to these accounts:

"The Yuezhi originally lived in the area between the Qilian or Heavenly Mountains (Tian Shan) and Dunhuang, but after they were defeated by the Xiongnu they moved far away to the west, beyond Dayuan, where they attacked and conquered the people of Daxia and set up the court of their king on the northern bank of the Gui [= Oxus] River. A small number of their people who were unable to make the journey west sought refuge among the Qiang barbarians in the Southern Mountains, where they are known as the Lesser Yuezhi."[1]

The Yuezhi may have been a Caucasoid people, as indicated by the portraits of their kings on the coins they struck following their exodus to Transoxiana (2nd-1st century BCE), some old place names in Gansu explainable in Tocharian languages,[19] and especially the coins they struck in India as Kushans (1st-3rd century CE). However, no direct records for the name of Yuezhi rulers are known to exist (only Chinese accounts mention the names.), and there is some doubt about the authenticity of their earliest coins.[20] No Caucasoid skulls were found by archaeologists at the Yuezhi homeland in Gansu, and a site thought to be of Yuezhi and Huns found in the Barkol County showed characteristics similar to a culture in Inner Mongolia.[21][22][23]

Ancient Chinese sources do describe the existence of "white people with long hair" (the Bai people of the Shan Hai Jing) beyond their northwestern border. Very well-preserved Tarim mummies with Caucasian features, today displayed at the Ürümqi Museum and dated to the 3rd century BCE, were found at the ancient oasis on the Silk Road, Niya.[24] However, the attribution of reddish or blond hair to these mummies may be in error, since the reddish color can occurs as a result of decomposition over several hundred years (for example, even African mummies also have so-called reddish hair but are clearly not White or European). Notwithstanding, genetic testing and skull examples have shown conclusively that Caucasian genetic material is present in this area. Blond hair among the Tocharian mummies is common, as with certain populations in modern Central Asia and the Middle East.

Evidence of the Indo-EuropeanTocharian languages also has been found in the same geographical area, Although the first known epigraphic evidence dates to the 6th century CE, the degree of differentiation between Tocharian A and Tocharian B and the absence of Tocharian language remains beyond that area suggest that a common Tocharian language existed in the same area of Yuezhi settlement during the second half of the 1st millennium BCE.

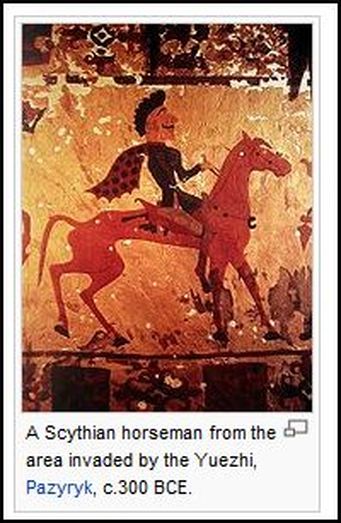

According to one theory, the Yuezhi were probably part of the large migration of Indo-European-speaking peoples who were settled in eastern Central Asia (possibly as far east as Gansu) at that time. The nomadic people of the Ordos culture, who lived in northern China, east of the Yuezhi, are another example. Also, the Caucasian mummies of Pazyryk, which were probably Scythian in origin, were found around 1,500 kilometers northwest of the Yuezhi and date to around the 3rd century BCE.[citation needed]

According to Han Dynasty accounts, the Yuezhi "were flourishing" during the time of the first great Chinese Qin emperor, but were regularly in conflict with the neighboring tribe of the Xiongnu to the Northeast.

[edit] The Yuezhi exodus The Yuezhi were settled at the doorstep of Qin China in the 3rd century BCE. A Scythian horseman from the area invaded by the Yuezhi, Pazyryk, c.300 BCE. The Yuezhi sometimes practiced the exchange of hostages with the Xiongnu, and, at one time, were hosts to Modu Shanyu (冒頓), son of the Xiongnu leader. Modu stole a horse and escaped when the Yuezhi tried to kill him in retaliation for an attack by his father. Modu subsequently became ruler of the Xiongnu after killing his father.

Shortly before 174 BCE,[citation needed] led by one of Modu's tribal chiefs, the Xiongnu invaded Yuezhi territory in the Gansu region and achieved a crushing victory. Modu boasted in a letter (174 BCE) to the Han emperor[citation needed] that due to "the excellence of his fighting men, and the strength of his horses, he has succeeded in wiping out the Yuezhi, slaughtering or forcing to submission every number of the tribe." The son of Modu, Laoshang Chanyu, subsequently killed the king of the Yuezhi and, in accordance with nomadic traditions, "made a drinking cup out of his skull." (Shiji 123. Watson 1961:231).

Following Chinese sources, a large part of the Yuezhi people therefore fell under the domination of the Xiongnu, and these may have been the ancestors of the Tocharian speakers attested in the 6th century CE. A very small group of Yuezhi fled south to the territory of the Proto-TibetanQiang and came to be known to the Chinese as the "Small Yuezhi". According to the Hanshu, they only numbered around 150 families.

Finally, a large group of the Yuezhi fled from the Tarim Basin/Gansu area towards the Northwest, first settling in the Ili valley, immediately north of the Tian ShanSakas or Scythians): "The Yuezhi attacked the king of the Sai who moved a considerable distance to the south and the Yuezhi then occupied his lands" (Han Shu 61 4B). The Sai undertook their own migration, which was to lead them as far as Kashmir, after travelling through a "Suspended Crossing" (probably the Khunjerab Pass between present-day Xinjiang and northern Pakistan). The Sakas ultimately established an Indo-Scythian kingdom in northern India.[citation needed]

After 155 BCE, the Wusun, in alliance with the Xiongnu and out of revenge from an earlier conflict, managed to dislodge the Yuezhi, forcing them to move south. The Yuezhi crossed the neighbouring urban civilization of the Dayuan in Ferghana and settled on the northern bank of the Oxus, in the region of Transoxiana, in modern-day Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, just north of the Hellenistic Greco-Bactrian kingdom. The Greek city of Alexandria on the Oxus was apparently burnt to the ground by the Yuezhi around 145 BCE.[25]

[edit] Settlement in Transoxiana The Chinese mission of Zhang Qian to the Yuezhi in 126 BCE, Mogao Caves, 618-712 CE mural painting The Yuezhi were visited by a Chinese mission, led by Zhang Qian in 126 BCE,[26] that was seeking an offensive alliance with the Yuezhi to counter the Xiongnu threat to the north. Although the request for an alliance was denied by the son of the slain Yuezhi king, who preferred to maintain peace in Transoxiana rather than to seek revenge, Zhang Qian made a detailed account, reported in the Shiji, that gives considerable insight into the situation in Central Asia at that time.[27]