Lithuanian > Polish Royalty

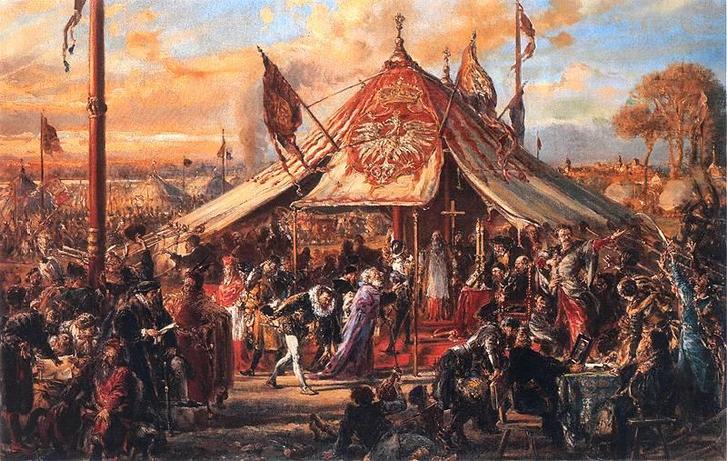

Matejko, Baptism of Lithuania

Polish Lithuanian Background

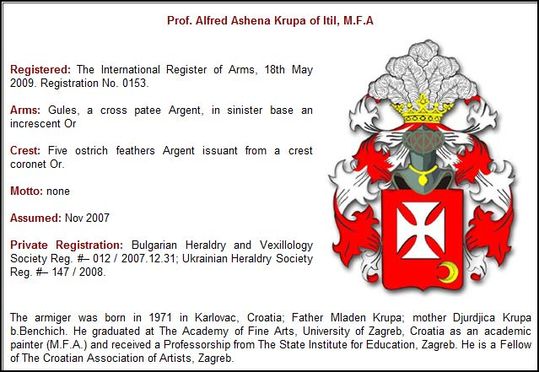

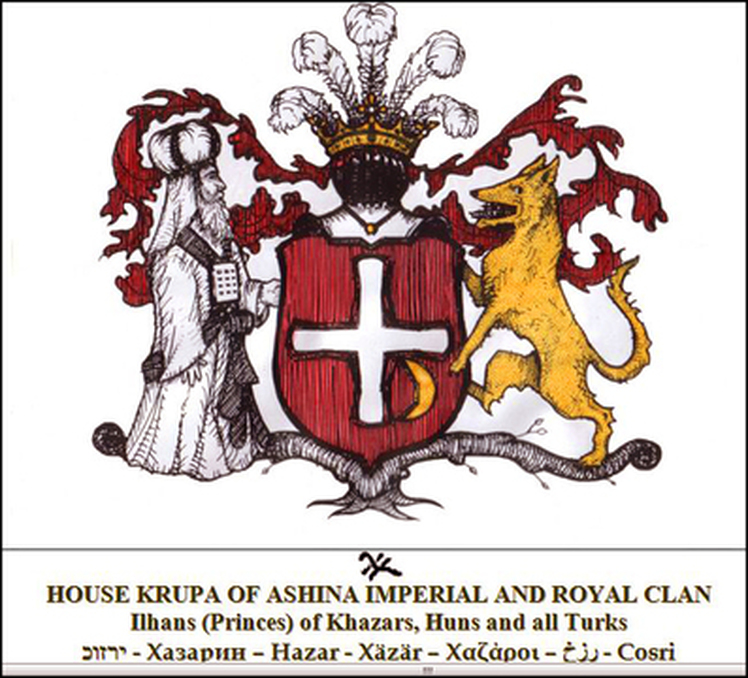

ALFRED FREDDY KRUPA prof. MFA

THE GENETIC-GENEALOGY RESEARCH OUTCOME REPORT

KRUPA; Szlachta Polska pochodzenia ż'ydowskiego

(Polish nobility of Jewish extraction)

„JERUSALEM NOBLES“

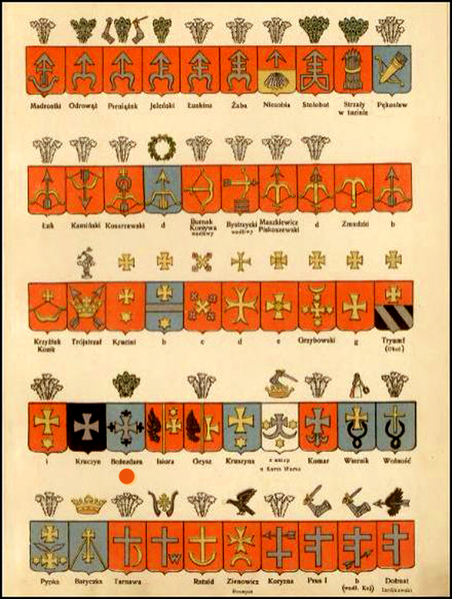

Tarnawa according to Herby szlachty polskiej,

by Zbigniew Leszczyc (1908)

Genetic-genealogy is the science and tool for genealogist where paper trail do not exist anymore and researchers faced „brick wall“. Krupa family DNA through Alfred Freddy Krupa has been examined by several Y-DNA tests (non-recombining male only DNA) in 2007 and 2009, and autosomal DNA (atDNA) test (Family Finder and Population Finder) browsing all 22 chromosome in each generation re-combining DNA, in 2011.

KRUPA POLISH –LITHUANIAN HEBREW NOBILITY LEGAL FACTS

Alfred Krupa prof. M.F.A. in Painting (grandfather of Alfred Freddy Krupa prof.M.F.A.) was born on 22nd of July 1915 in Mikolow,Poland, baptismal name Joseph (paper trail trough his Yugoslavian death certificate and Polish birth certificate), by father Jan Krupa and mother Anastasia Krupa born Podkowa (name associated with noble Clan Dabrowa).

In time of his birth nobility sytem formed in Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, was still nominally on power. 6 years later, after the adoption of the March Constitution in 1921, the privileges, customs and rules of the nobility were finaly and officially abolished in Poland. This include requirements for Jews to receive prerogatives of nobility.

His father Jan Krupa (name associated with noble Clan Tarnawa) was baptised as well, and as Roman Catholic-Polish killed in the Polish-Ukrainian War (Polish minority upraising,led by POLISH NOBILITY) in 1919 (it looks, eventually that he became member of the Polish Underground Organisation in Lvow or somewhere else in Galicia and as such murdered by russified Ukrainians).

Mother Anastasia Krupa born Podkowa died the same year – 1919.

This Krupa family is of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Russia, as visible in lists of 12, 25, 37 and 67 Y-DNA matches, within containing significant number of matches with Levit tradition (and some of Cohanim tradition). The most closest match is Abelman family from Seredzius, Lithuania (67 markers, gen.dist.-2).

TMRCA calculations show that Krupa family branched from them some 200-350 years ago (some 8-14 /95%/ generations or more).

There is mention (the very last known mention) of the Krupa family in year 1800 , AS A NOBLE FAMILY in book «List of Nobility of Bila Tzerkva (Ukraine) in 1800», in village Bosivka (published in 2001 in Ukraine).

DNA test /obtained in the FamilyTree DNA, Houston/ of Krupa de Tarnawa Y DNA showed that one of CLOSE Y-DNA 67 male matches is M. Shainis from New York, who's most distant known ancestor was Joseph Shainis, born in 1843 in Bila Tzerkva, Ukraine.

All autosomal DNA Jewish matches of Alfred Freddy Krupa are from Ukraine in range of 6th and 7th cousin.

In independent confirmation of above, „witness“ Prince (Ksiaze) Waclaw Podbereski (1st president of the Confederation of Polish Nobility, Gdansk, during Mladen Krupa's reception into membership,2003) stated that he „knows about noble Krupa's from Ukraine who moved to Poland in 19th century“. http://herbarz.net/Forumnobilium/Rody%20ZSzP.htm, e-mail correspodence archive with the CPN

Bennet Greenspan founder of the oldest and largest genetic-genealogy organization analysing results of Family/Population Finder test (autosomal DNA), on 29th October 2011 concluded that Krupa family converted and intermarried with non-jews sometime prior to 1825 (at latest).

It means that first Krupa male (still of unknown name) was baptised sometime when 3rd Lithuanian statute has been on power (up to 1840). And possibly in terms of Shabbatean-Frankist Jewish movement mass conversion and adoption into nobility. This is coherent with family oral tradition and what has been told to us by other people.

Jewish converts joined rank of Szlachta on the basis of a Lithuanian statute of 1588, which gave the prerogatives of the nobility to baptizing Jews and their offspring. Lithuanian statute of 1588 has been on power up to 1840 when Russian Tzar abolished it. Ruthenia (Ukraine) was under authority of the Lithuanian statute, but as integral part of „the Crown“ /Korrona/of Poland, laws,customs and regulations of both parts of the Commonwealth was enforced equally /bordering territory/.

In Polish part of the Commonwealth Jews has been adopted into nobility on custom basis.

In both cases, based on statute or custom, Jews has been given full prerogatives of nobility along with baptism by automatism.

Upon joining the Catholic Church the Jews received nobilitation and came into possession of the golden liberties of the nobility, the highest privilege the Republic could offer.

Despite the fact we dont know exact date of baptism-conversion from Judaism to Roman Catholic (but it is absolutely certain sometime earlier than 1825, and not prior 1700), Krupa family (descendants of Alfred Krupa, born prior March Constitution of 1921) are fully entitled to claim noble status and ancestry, both on customary and statutary basis.

Declaration/statement of Roman Catholic Church affiliation or baptismal certificate was lawfull and final proof of nobility for converted Jews until, at latest- 1921, and its offsprings in unbroken male line AD INFINITUM.

Mayor Mladen Krupa M.Sc., son of Alfred Krupa, has been legitimized by the Polish Nobility Association-USA (2003) and Confederation of Polish Nobility-Poland (2003), while Alfred Freddy Krupa, son of Mladen Krupa, has been accepted into the Ruthenian (Ukrainian) Nobility Association-Ukraine (2009).

References;

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashkenazi#DNA_clues

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Szlachta

http://www.jurzak.pl/gd/szablony/herb.php?lang=en&id=0158

http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/biography/frankj.html

http://herbarz.net/Forumnobilium/Rody%20ZSzP.htm, e-mail correspodence archive with the CPN

www.polish-heroes.org

The Ukrainian-Polish War in Galicia O. Horbač – taken from Ukraine: a Concise Encyclopedia

The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, to be published by the Yale University Press

Zbigniew P. Szczęsny (Warsaw, Poland)

WHAT WE KNOW TODAY ABOUT KRUPA-TARNAWA FAMILY?

Krupa in the Kingdom of Poland as a name /form of address, title ,name,nickname/ is recorded first in 1204, and as family and noble is mentioned /recorded as such in old armorials/ first in 1450 (PETRUS KRUPA DE TARNAWA),

and after that in every century with just one or two names, with «holes» in time of hundred or more years, without showing blood /biological/ or some other particular familiar connection between those persons, but always with the very same Clan arms - Tarnawa http://www.jurzak.pl/gd/szablony/herb.php?lang=en&id=0158/ except Gozdawa arms, but that is actually Peplovski family, not Krupa.

As a result of this, today we do not know are they all one single or several male Y-DNA lines, or this CoA was assigned to people of the same surname but of differ-ent origin under various circumstances and reasons, before nobility was granted by the way of letters patent, or any other registered event;

1.Polska Encyklopedja Szlachecka, vol.VII, pg.170

2.Herbarz Polski (A.Boniecki), vol.XII, pg.342

3.Rodzina-Herbarz Szlachty Polskiej (S.hr Uruski), vol.VIII, pg.89

4.List of Nobility of Bila Tzerkva, pg.37

5.Herby Rodow Polski, pg.312

6.Polskie Rody Szlachty I Ich Herby, pg.107

7.Spis rycerstwa polskiego walczacego z Janem III pod Wienem

8.Kasprzycki (compedia), vol.VIII, pg.170

9.Zernicki (compedia), vol.I, pg.479

10.Szlachta zagrodova (Zernicki, 1907.)

11.Liber Beneficiorum Ecclesiae Creceviensis (J.Dlugosz)

12.Koronna Metrika

13.Polnische Klein Adel Register (web site)

14.Polish-Lithuanian Armorials of Tadeusz Gajl

Krupa h.Tarnawa family is also recorded /in the same sources/ in number of

different locations of former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, with different

occupations and wealth;

1. Estate Obrazowo, near Sandomierz (1450.,1460.,1470.)

2. Group of villages in Skwarczynska Wola (1539.)

3. Flower Mill in Pusnow (1541.)

4. Village Bosivka, Bila Tzerkva in Ruthenia /Ukraine/(1800.)

5. City House in Mikolow (19th century-1942.)

6. Surrounding of the Castle Drohyczin

7. Knights under command of the king Jan III Sobieski (1683.)

8. Krupa village in Belarus (establ.before 1450.)-not explained connection

* Plus list of recorded names without listed properties (estates) including

16th and 17th century

Original latin text of J.Dlugosz from 15th century ,speaks about noble Krupa de Tarnawa family.

Later sources and Polish versions speaks about Krupa h.(herb) Tarnawa family which is essentially different thing. Krupa de Tarnawa in translation means Krupa of Tarnawa or Krupa from Tarnawa, designating Tarnawa as a place/location (like in German; Von). In opposition to that Krupa herb Tanawa in translation means just Krupa Coat of Arms Tarnawa. This form was accepted in all later (newer) texts, but original description, probably the most true one, is of outstanding importance as we are now discovering full match Tarnawa-Krupa CoA/places/Y-DNA link from Kingdom of Poland to Central Asia.

As often in case of Polish Nobility , only surviving in memory of older generations, with lack of paper trail, time and way of original nobilitation of Krupa de Tarnawa family not recorded in historical records.

WHAT WE KNOW ABOUT POLISH NOBILITY?

Polish legend speaks of a Jewish king, Abraham Prokownik, to whom the Polish tribes swore allegiance before he abdicated in favor of Piast. Whether Abraham was a Khazar dynast or viceroy, an Ashkenazi migrant from the west, or a purely mythological figure is a matter of some debate. The tale has it that he was granted the throne when the nobility, having cast out Popiel, agreed to retain as King the first man to step through the city gates the next morning - he is said to have declined the honour and insisted that the wheelwright Piast would make the best. http://web.raex.com/~obsidian/baltic.htmlruler.

Saul Wahl is a legendary figure whose historicity cannot be confirmed and whose existence is dubious. Nevertheless, the story is widespread, and deserves to be commented upon. Saul is said to have been the son of a Rabbi of Padua (Samuel Judah Katzenellenbogen). Gifted with extraordinary wisdom, he was found by a Polish Noble (Nicholas Radziwill) who had been assisted by Saul's father in Italy and asked to search for him - finding him living in penurious circumstances in Brest-Litovsk, Radziwill is said to have favoured Saul with gifts and influence. When Stephen Bathory died, circumstances were such that Radziwill was offered the throne pro tempore, until a permanent candidate could be found, but he refused, saying that a much wiser man than he was a better candidate. He prevailed upon the Polish Sejm to elect Saul as rex pro tempore, and Saul is said to have discharged his office for a short time in very creditable fashion. Again, it isn't a very likely tale, but it does point up the fact the Jewish community in Greater Poland was very large and relatively influential during the Middle Ages.http://web.raex.com/~obsidian/baltic.htmlruler.

The Polish Nobility emerged as a clan (family or tribe) system before 1000 A.D. Each clan had its own mark, a tamga, which eventually evolved into the symbols found on Polish coats of arms. The noble class became landowners. Most noblemen in Poland and Lithuania claimed only to belong to the szlachta odwieczna or immemorial nobility. This meant that all knowledge of their origins had long since been lost, and was beyond their memory. Szlachta combined "high birth" and "military prowess" together in medieval times. Nobles were originally tribal chiefs. Poland had a large nobility. About ten percent (10%) of the population was noble, as compared to the one (1%) to two (2%) percent in the rest of Europe. The Polish State was set up to serve the Polish nobleman.

Margaret Odrowaz Sypnievska - http://www.angelfire.com/mi4/polcrt/PolNobility.html

The Polish term "szlachta" designates the formalized, hereditary noble class. In official Latin documents the old Commonwealth hereditary szlachta is referred to as "nobilitas" and is equivalent to the English nobility. There used to be a widespread misconception to translate "szlachta" as "gentry", because some nobles were poor. Some were even poorer than the non-noble gentry that declined with the 'second serfdom' and re-emerged after the Partitions. Some would even become tenants to the gentry but still kept their constitutional superiority. But it's not wealth or lifestyle (as with the gentry) but a hereditary legal status of a nobleman that makes you one. A specific nobleman was called a "szlachcic", and a noblewoman, a "szlachcianka." http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Szlachta

Szlachta (shlákh-ta) comes from the Old German slahta that is now schlagen (to strike, fight, cleave, breed) and Geschlecht (sex, species, family race). It came from the Polish language via a Czech word slehta (nobility). The szlachta were a blend of "high birth" and "military prowess." In Poland, a coat of arms was shared by many members of the same clan, based on various criteria.

In the fifteenth century, there were 139 clans. In 1584, there were 107 clans, and today there are several hundred* (209).

In the beginning, members of the same clan were neighbors and fought together in battle. As people moved around, of course, the clans were located in all parts of Poland. http://pnaf.us/polenobility.htm

… szlachta simply addressed each other by their given name or as "Sir

Brother" (Panie bracie) or the feminine equivalent.

The other forms of address would be "Illustrious and Magnificent Lord", "Magnificent Lord", "Generous Lord" or "Noble Lord" (in decreasing order) or simply "His/Her Grace Lord/Lady XYZ".

(Wikipedia about Szlachta)

Mayor Mladen Krupa M.Sc., son of Alfred Krupa, has been legitimized by the Polish Nobility Association-USA (2003) and Confederation of Polish Nobility-Poland (2003), while Alfred Freddy Krupa, son of Mladen Krupa, has been accepted into the Ruthenian (Ukrainian) Nobility Association-Ukraine (2009).

THE GENETIC-GENEALOGY RESEARCH OUTCOME REPORT

KRUPA; Szlachta Polska pochodzenia ż'ydowskiego

(Polish nobility of Jewish extraction)

„JERUSALEM NOBLES“

Tarnawa according to Herby szlachty polskiej,

by Zbigniew Leszczyc (1908)

Genetic-genealogy is the science and tool for genealogist where paper trail do not exist anymore and researchers faced „brick wall“. Krupa family DNA through Alfred Freddy Krupa has been examined by several Y-DNA tests (non-recombining male only DNA) in 2007 and 2009, and autosomal DNA (atDNA) test (Family Finder and Population Finder) browsing all 22 chromosome in each generation re-combining DNA, in 2011.

KRUPA POLISH –LITHUANIAN HEBREW NOBILITY LEGAL FACTS

Alfred Krupa prof. M.F.A. in Painting (grandfather of Alfred Freddy Krupa prof.M.F.A.) was born on 22nd of July 1915 in Mikolow,Poland, baptismal name Joseph (paper trail trough his Yugoslavian death certificate and Polish birth certificate), by father Jan Krupa and mother Anastasia Krupa born Podkowa (name associated with noble Clan Dabrowa).

In time of his birth nobility sytem formed in Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, was still nominally on power. 6 years later, after the adoption of the March Constitution in 1921, the privileges, customs and rules of the nobility were finaly and officially abolished in Poland. This include requirements for Jews to receive prerogatives of nobility.

His father Jan Krupa (name associated with noble Clan Tarnawa) was baptised as well, and as Roman Catholic-Polish killed in the Polish-Ukrainian War (Polish minority upraising,led by POLISH NOBILITY) in 1919 (it looks, eventually that he became member of the Polish Underground Organisation in Lvow or somewhere else in Galicia and as such murdered by russified Ukrainians).

Mother Anastasia Krupa born Podkowa died the same year – 1919.

This Krupa family is of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Russia, as visible in lists of 12, 25, 37 and 67 Y-DNA matches, within containing significant number of matches with Levit tradition (and some of Cohanim tradition). The most closest match is Abelman family from Seredzius, Lithuania (67 markers, gen.dist.-2).

TMRCA calculations show that Krupa family branched from them some 200-350 years ago (some 8-14 /95%/ generations or more).

There is mention (the very last known mention) of the Krupa family in year 1800 , AS A NOBLE FAMILY in book «List of Nobility of Bila Tzerkva (Ukraine) in 1800», in village Bosivka (published in 2001 in Ukraine).

DNA test /obtained in the FamilyTree DNA, Houston/ of Krupa de Tarnawa Y DNA showed that one of CLOSE Y-DNA 67 male matches is M. Shainis from New York, who's most distant known ancestor was Joseph Shainis, born in 1843 in Bila Tzerkva, Ukraine.

All autosomal DNA Jewish matches of Alfred Freddy Krupa are from Ukraine in range of 6th and 7th cousin.

In independent confirmation of above, „witness“ Prince (Ksiaze) Waclaw Podbereski (1st president of the Confederation of Polish Nobility, Gdansk, during Mladen Krupa's reception into membership,2003) stated that he „knows about noble Krupa's from Ukraine who moved to Poland in 19th century“. http://herbarz.net/Forumnobilium/Rody%20ZSzP.htm, e-mail correspodence archive with the CPN

Bennet Greenspan founder of the oldest and largest genetic-genealogy organization analysing results of Family/Population Finder test (autosomal DNA), on 29th October 2011 concluded that Krupa family converted and intermarried with non-jews sometime prior to 1825 (at latest).

It means that first Krupa male (still of unknown name) was baptised sometime when 3rd Lithuanian statute has been on power (up to 1840). And possibly in terms of Shabbatean-Frankist Jewish movement mass conversion and adoption into nobility. This is coherent with family oral tradition and what has been told to us by other people.

Jewish converts joined rank of Szlachta on the basis of a Lithuanian statute of 1588, which gave the prerogatives of the nobility to baptizing Jews and their offspring. Lithuanian statute of 1588 has been on power up to 1840 when Russian Tzar abolished it. Ruthenia (Ukraine) was under authority of the Lithuanian statute, but as integral part of „the Crown“ /Korrona/of Poland, laws,customs and regulations of both parts of the Commonwealth was enforced equally /bordering territory/.

In Polish part of the Commonwealth Jews has been adopted into nobility on custom basis.

In both cases, based on statute or custom, Jews has been given full prerogatives of nobility along with baptism by automatism.

Upon joining the Catholic Church the Jews received nobilitation and came into possession of the golden liberties of the nobility, the highest privilege the Republic could offer.

Despite the fact we dont know exact date of baptism-conversion from Judaism to Roman Catholic (but it is absolutely certain sometime earlier than 1825, and not prior 1700), Krupa family (descendants of Alfred Krupa, born prior March Constitution of 1921) are fully entitled to claim noble status and ancestry, both on customary and statutary basis.

Declaration/statement of Roman Catholic Church affiliation or baptismal certificate was lawfull and final proof of nobility for converted Jews until, at latest- 1921, and its offsprings in unbroken male line AD INFINITUM.

Mayor Mladen Krupa M.Sc., son of Alfred Krupa, has been legitimized by the Polish Nobility Association-USA (2003) and Confederation of Polish Nobility-Poland (2003), while Alfred Freddy Krupa, son of Mladen Krupa, has been accepted into the Ruthenian (Ukrainian) Nobility Association-Ukraine (2009).

References;

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashkenazi#DNA_clues

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Szlachta

http://www.jurzak.pl/gd/szablony/herb.php?lang=en&id=0158

http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/biography/frankj.html

http://herbarz.net/Forumnobilium/Rody%20ZSzP.htm, e-mail correspodence archive with the CPN

www.polish-heroes.org

The Ukrainian-Polish War in Galicia O. Horbač – taken from Ukraine: a Concise Encyclopedia

The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, to be published by the Yale University Press

Zbigniew P. Szczęsny (Warsaw, Poland)

WHAT WE KNOW TODAY ABOUT KRUPA-TARNAWA FAMILY?

Krupa in the Kingdom of Poland as a name /form of address, title ,name,nickname/ is recorded first in 1204, and as family and noble is mentioned /recorded as such in old armorials/ first in 1450 (PETRUS KRUPA DE TARNAWA),

and after that in every century with just one or two names, with «holes» in time of hundred or more years, without showing blood /biological/ or some other particular familiar connection between those persons, but always with the very same Clan arms - Tarnawa http://www.jurzak.pl/gd/szablony/herb.php?lang=en&id=0158/ except Gozdawa arms, but that is actually Peplovski family, not Krupa.

As a result of this, today we do not know are they all one single or several male Y-DNA lines, or this CoA was assigned to people of the same surname but of differ-ent origin under various circumstances and reasons, before nobility was granted by the way of letters patent, or any other registered event;

1.Polska Encyklopedja Szlachecka, vol.VII, pg.170

2.Herbarz Polski (A.Boniecki), vol.XII, pg.342

3.Rodzina-Herbarz Szlachty Polskiej (S.hr Uruski), vol.VIII, pg.89

4.List of Nobility of Bila Tzerkva, pg.37

5.Herby Rodow Polski, pg.312

6.Polskie Rody Szlachty I Ich Herby, pg.107

7.Spis rycerstwa polskiego walczacego z Janem III pod Wienem

8.Kasprzycki (compedia), vol.VIII, pg.170

9.Zernicki (compedia), vol.I, pg.479

10.Szlachta zagrodova (Zernicki, 1907.)

11.Liber Beneficiorum Ecclesiae Creceviensis (J.Dlugosz)

12.Koronna Metrika

13.Polnische Klein Adel Register (web site)

14.Polish-Lithuanian Armorials of Tadeusz Gajl

Krupa h.Tarnawa family is also recorded /in the same sources/ in number of

different locations of former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, with different

occupations and wealth;

1. Estate Obrazowo, near Sandomierz (1450.,1460.,1470.)

2. Group of villages in Skwarczynska Wola (1539.)

3. Flower Mill in Pusnow (1541.)

4. Village Bosivka, Bila Tzerkva in Ruthenia /Ukraine/(1800.)

5. City House in Mikolow (19th century-1942.)

6. Surrounding of the Castle Drohyczin

7. Knights under command of the king Jan III Sobieski (1683.)

8. Krupa village in Belarus (establ.before 1450.)-not explained connection

* Plus list of recorded names without listed properties (estates) including

16th and 17th century

Original latin text of J.Dlugosz from 15th century ,speaks about noble Krupa de Tarnawa family.

Later sources and Polish versions speaks about Krupa h.(herb) Tarnawa family which is essentially different thing. Krupa de Tarnawa in translation means Krupa of Tarnawa or Krupa from Tarnawa, designating Tarnawa as a place/location (like in German; Von). In opposition to that Krupa herb Tanawa in translation means just Krupa Coat of Arms Tarnawa. This form was accepted in all later (newer) texts, but original description, probably the most true one, is of outstanding importance as we are now discovering full match Tarnawa-Krupa CoA/places/Y-DNA link from Kingdom of Poland to Central Asia.

As often in case of Polish Nobility , only surviving in memory of older generations, with lack of paper trail, time and way of original nobilitation of Krupa de Tarnawa family not recorded in historical records.

WHAT WE KNOW ABOUT POLISH NOBILITY?

Polish legend speaks of a Jewish king, Abraham Prokownik, to whom the Polish tribes swore allegiance before he abdicated in favor of Piast. Whether Abraham was a Khazar dynast or viceroy, an Ashkenazi migrant from the west, or a purely mythological figure is a matter of some debate. The tale has it that he was granted the throne when the nobility, having cast out Popiel, agreed to retain as King the first man to step through the city gates the next morning - he is said to have declined the honour and insisted that the wheelwright Piast would make the best. http://web.raex.com/~obsidian/baltic.htmlruler.

Saul Wahl is a legendary figure whose historicity cannot be confirmed and whose existence is dubious. Nevertheless, the story is widespread, and deserves to be commented upon. Saul is said to have been the son of a Rabbi of Padua (Samuel Judah Katzenellenbogen). Gifted with extraordinary wisdom, he was found by a Polish Noble (Nicholas Radziwill) who had been assisted by Saul's father in Italy and asked to search for him - finding him living in penurious circumstances in Brest-Litovsk, Radziwill is said to have favoured Saul with gifts and influence. When Stephen Bathory died, circumstances were such that Radziwill was offered the throne pro tempore, until a permanent candidate could be found, but he refused, saying that a much wiser man than he was a better candidate. He prevailed upon the Polish Sejm to elect Saul as rex pro tempore, and Saul is said to have discharged his office for a short time in very creditable fashion. Again, it isn't a very likely tale, but it does point up the fact the Jewish community in Greater Poland was very large and relatively influential during the Middle Ages.http://web.raex.com/~obsidian/baltic.htmlruler.

The Polish Nobility emerged as a clan (family or tribe) system before 1000 A.D. Each clan had its own mark, a tamga, which eventually evolved into the symbols found on Polish coats of arms. The noble class became landowners. Most noblemen in Poland and Lithuania claimed only to belong to the szlachta odwieczna or immemorial nobility. This meant that all knowledge of their origins had long since been lost, and was beyond their memory. Szlachta combined "high birth" and "military prowess" together in medieval times. Nobles were originally tribal chiefs. Poland had a large nobility. About ten percent (10%) of the population was noble, as compared to the one (1%) to two (2%) percent in the rest of Europe. The Polish State was set up to serve the Polish nobleman.

Margaret Odrowaz Sypnievska - http://www.angelfire.com/mi4/polcrt/PolNobility.html

The Polish term "szlachta" designates the formalized, hereditary noble class. In official Latin documents the old Commonwealth hereditary szlachta is referred to as "nobilitas" and is equivalent to the English nobility. There used to be a widespread misconception to translate "szlachta" as "gentry", because some nobles were poor. Some were even poorer than the non-noble gentry that declined with the 'second serfdom' and re-emerged after the Partitions. Some would even become tenants to the gentry but still kept their constitutional superiority. But it's not wealth or lifestyle (as with the gentry) but a hereditary legal status of a nobleman that makes you one. A specific nobleman was called a "szlachcic", and a noblewoman, a "szlachcianka." http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Szlachta

Szlachta (shlákh-ta) comes from the Old German slahta that is now schlagen (to strike, fight, cleave, breed) and Geschlecht (sex, species, family race). It came from the Polish language via a Czech word slehta (nobility). The szlachta were a blend of "high birth" and "military prowess." In Poland, a coat of arms was shared by many members of the same clan, based on various criteria.

In the fifteenth century, there were 139 clans. In 1584, there were 107 clans, and today there are several hundred* (209).

In the beginning, members of the same clan were neighbors and fought together in battle. As people moved around, of course, the clans were located in all parts of Poland. http://pnaf.us/polenobility.htm

… szlachta simply addressed each other by their given name or as "Sir

Brother" (Panie bracie) or the feminine equivalent.

The other forms of address would be "Illustrious and Magnificent Lord", "Magnificent Lord", "Generous Lord" or "Noble Lord" (in decreasing order) or simply "His/Her Grace Lord/Lady XYZ".

(Wikipedia about Szlachta)

Mayor Mladen Krupa M.Sc., son of Alfred Krupa, has been legitimized by the Polish Nobility Association-USA (2003) and Confederation of Polish Nobility-Poland (2003), while Alfred Freddy Krupa, son of Mladen Krupa, has been accepted into the Ruthenian (Ukrainian) Nobility Association-Ukraine (2009).

"The first Jews to settle in Lithuania in the 11th century came from the land of the Khazars, on the lower Volga River, from Crimea on the Black Sea and from Bohemia. Originally, the Jews came to the land of the Khazars from the Byzantine kingdom, where they had been oppressed. The Khazars had welcomed the Jews and later had been converted to Judaism. When the Khazars were overrun by the Mongols and Russians, the Jews settled in Lithuania, whose rulers, at that time, were extremely tolerant."

Royal Ashina Khazars were inducted into Polish Nobility as Catholics

Casimir III the Great treated the Jews of Poland well, and was known as the King of the Serfs and Jews.

Lithuanian-Polish Royals

Not all kings of Poland were Polish. There is nothing exceptional in that - after all, the present royal house of Britain is of German origin. King Louis (1370-1382) was a member of the French House of Anjou, founded by Saint Louis, but he was also king of Hungary, Poland, Dalmatia, Croatia, Rama, Serbia, Galicia, Lodomeria, Romania and Bulgaria. The vast empire of the Anjou dynasty did not promise to last long, as Louis had as yet no issue. Later he had two daughters: the princesses Elisabeth and Jadwiga, who became Queen of Poland in 1384.

Lithuania was at the time a major power. It extended over the territories now known as Bielorussia and Ukraine. It was in conflict with Poland and several battles were fought. The Polish senators, however, planned a masterpiece of statesmanship: a marriage of Grand Duke Jagiello with Queen Jadwiga. It would be a great sacrifice on her part, as the grand duke was three times her age and she was a beauty.

Jagiello was baptized in the Catholic faith and took the name of Wladyslaw. The Lithuanians were at the time pagans, worshipping snakes. Jagiello's brother Witold was also baptized. The union of Poland and Lithuania was not an annexation. Lithuania retained its identity and kept it for centuries, but the King of Poland was also Grand Duke of Lithuania.

The union of the two nations resulted in the largest power in Europe and remained in force for the following centuries. Some of the greatest men of Poland - such as the poet Mickiewicz in the 19th century and the national leader Pilsudski in the 20th - were of Lithuanian origin, but they did not know the Lithuanian language which, unlike Polish, is not a Slavonic language. The population of Lithuania was largely Ruthenian.

Jagiello proved to be a great statesman and became the founder of the Jagiellonian dynasty, which ruled the union for centuries.

Both Lithuania and Poland had been attacked by the Order of Teutonic Knights, a military order based in East Prussia. The German order was a major power which endeavored to extend its area eastward and south, and the Teutonic Knights were armed better than most European nations. Yet when the Teutonic Knights attacked in 1410, the united Polish and Lithuanian forces under the command of Jagiello defeated them in the great battle of Grunwald. Thus the Prussian efforts to conquer the entire Baltic coast and the northern provinces of the Polish-Lithuanian union were finished forever.

The last Jagiellonian king was Zygmunt-August (1548-1572). He was followed by Henri de Valois, a Frenchman. The next kings were Stefan Batory, a Hungarian, and Zygmunt Vasa, a Swede. The throne of the Polish-Lithuanian union was elective - a democratic feature unknown in other European countries. Foreign princes were elected largely because a Polish king might be considered as a favor for Poland and a Lithuanian one a favor for his country, while a foreigner was neutral.

Nevertheless, one of the best kings was Jan Sobieski (1674-1696), who saved Europe from a Turkish invasion. The Ottoman empire was then a major power. Its huge army besieged Vienna, which had it been seized it would have meant the victorious Turkish army would continue its invasion and thus place western Europe in mortal danger. Jan Sobieski, a great commander, saved Europe. His letters to his wife, a French princess, are a literary masterpiece.

The last king of the Union was Stanislaw Poniatowski (1764-1795).

http://www.theroyalforums.com/forums/f186/royal-families-of-poland-and-lithuania-4716.html

Lithuanian-Polish Royals

Not all kings of Poland were Polish. There is nothing exceptional in that - after all, the present royal house of Britain is of German origin. King Louis (1370-1382) was a member of the French House of Anjou, founded by Saint Louis, but he was also king of Hungary, Poland, Dalmatia, Croatia, Rama, Serbia, Galicia, Lodomeria, Romania and Bulgaria. The vast empire of the Anjou dynasty did not promise to last long, as Louis had as yet no issue. Later he had two daughters: the princesses Elisabeth and Jadwiga, who became Queen of Poland in 1384.

Lithuania was at the time a major power. It extended over the territories now known as Bielorussia and Ukraine. It was in conflict with Poland and several battles were fought. The Polish senators, however, planned a masterpiece of statesmanship: a marriage of Grand Duke Jagiello with Queen Jadwiga. It would be a great sacrifice on her part, as the grand duke was three times her age and she was a beauty.

Jagiello was baptized in the Catholic faith and took the name of Wladyslaw. The Lithuanians were at the time pagans, worshipping snakes. Jagiello's brother Witold was also baptized. The union of Poland and Lithuania was not an annexation. Lithuania retained its identity and kept it for centuries, but the King of Poland was also Grand Duke of Lithuania.

The union of the two nations resulted in the largest power in Europe and remained in force for the following centuries. Some of the greatest men of Poland - such as the poet Mickiewicz in the 19th century and the national leader Pilsudski in the 20th - were of Lithuanian origin, but they did not know the Lithuanian language which, unlike Polish, is not a Slavonic language. The population of Lithuania was largely Ruthenian.

Jagiello proved to be a great statesman and became the founder of the Jagiellonian dynasty, which ruled the union for centuries.

Both Lithuania and Poland had been attacked by the Order of Teutonic Knights, a military order based in East Prussia. The German order was a major power which endeavored to extend its area eastward and south, and the Teutonic Knights were armed better than most European nations. Yet when the Teutonic Knights attacked in 1410, the united Polish and Lithuanian forces under the command of Jagiello defeated them in the great battle of Grunwald. Thus the Prussian efforts to conquer the entire Baltic coast and the northern provinces of the Polish-Lithuanian union were finished forever.

The last Jagiellonian king was Zygmunt-August (1548-1572). He was followed by Henri de Valois, a Frenchman. The next kings were Stefan Batory, a Hungarian, and Zygmunt Vasa, a Swede. The throne of the Polish-Lithuanian union was elective - a democratic feature unknown in other European countries. Foreign princes were elected largely because a Polish king might be considered as a favor for Poland and a Lithuanian one a favor for his country, while a foreigner was neutral.

Nevertheless, one of the best kings was Jan Sobieski (1674-1696), who saved Europe from a Turkish invasion. The Ottoman empire was then a major power. Its huge army besieged Vienna, which had it been seized it would have meant the victorious Turkish army would continue its invasion and thus place western Europe in mortal danger. Jan Sobieski, a great commander, saved Europe. His letters to his wife, a French princess, are a literary masterpiece.

The last king of the Union was Stanislaw Poniatowski (1764-1795).

http://www.theroyalforums.com/forums/f186/royal-families-of-poland-and-lithuania-4716.html

Early Poland

The Chronicles and Deeds of the Dukes or Princes of the Poles by Gallus Anonymous, translated by Janos M. Bak. A 12th century account of Polish history from ancient times to the reign of Boleslaw III.

The Formation of the Polish State: The Period of Ducal Rule, 963-1194 by Tadeusz Manteuffel, translated by Andrew Gorski. Out of print, but available from Alibris.

Ottonian Germany: The Chronicon of Thietmar of Merseburg by Thietmar, translated by David A. Warner. One of the most important sources for the history of the 10th and early 11th centuries. Thietmar had opinions on everything, from politics to shocking women's fashions. He is arguably the single most important witness to the early history of Poland.

The Rise of the Polish Monarchy: Piast Poland in East Central Europe, 1320-1370 by Paul W. Knoll. Ending more than a century of division, Poland's last two Piast rulers, Wladyslaw Lokietek and his son Casimir the Great, forged the splintered country into a strong, independent monarchy. This is the first English-language account of the reigns of these two monarchs. From Alibris.

Jadwiga: Poland's Great Queen by Charlotte Hoffman Kellogg. A 1931 biography of the 14th century queen who founded the Jagiellon dynasty. From Alibris.

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth The Polish-Lithuanian State, 1386-1795 by Daniel Z. Stone. For four centuries, the Polish-Lithuanian state encompassed present-day Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, Russia, Latvia, Estonia, and Romania. Governed by a constitutional monarchy, it enjoyed unusual domestic tranquility.

The Polish-Lithuanian Monarchy in European Context: C. 1500-1795 edited by Richard Butterwick. Essays assessing the institution and idea of monarchy in one of Europe's largest and most neglected states.

The Other Prussia: Royal Prussia, Poland and Liberty, 1569-1772 deals with the elective monarchy in Poland.

More Books About Lithuania

The first extensive Jewish emigration from Western Europe to Poland occurred at the time of the First Crusade (1098). Under Boleslaw III Krzywousty (1102–1139), the Jews, encouraged by the tolerant régime of this ruler, settled throughout Poland, including over the border into Lithuanian territory as far as Kiev. At the same time Poland saw possible immigration of Khazars, a Turkic tribe that had converted to Judaism. Boleslaw on his part recognized the utility of the Jews it the development of the commercial interests of his country. The Prince of Kraków, Mieszko III the Old (1173–1202), in his endeavor to establish law and order in his domains, prohibited all violence against the Jews, particularly attacks upon them by unruly students (żacy). Boys guilty of such attacks, or their parents, were made to pay fines as heavy as those imposed for sacrilegious acts. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jewish_Polish_history_origins_to_1600s

Disambiguation - Sigismund was the name of several European nobles:

The Chronicles and Deeds of the Dukes or Princes of the Poles by Gallus Anonymous, translated by Janos M. Bak. A 12th century account of Polish history from ancient times to the reign of Boleslaw III.

The Formation of the Polish State: The Period of Ducal Rule, 963-1194 by Tadeusz Manteuffel, translated by Andrew Gorski. Out of print, but available from Alibris.

Ottonian Germany: The Chronicon of Thietmar of Merseburg by Thietmar, translated by David A. Warner. One of the most important sources for the history of the 10th and early 11th centuries. Thietmar had opinions on everything, from politics to shocking women's fashions. He is arguably the single most important witness to the early history of Poland.

The Rise of the Polish Monarchy: Piast Poland in East Central Europe, 1320-1370 by Paul W. Knoll. Ending more than a century of division, Poland's last two Piast rulers, Wladyslaw Lokietek and his son Casimir the Great, forged the splintered country into a strong, independent monarchy. This is the first English-language account of the reigns of these two monarchs. From Alibris.

Jadwiga: Poland's Great Queen by Charlotte Hoffman Kellogg. A 1931 biography of the 14th century queen who founded the Jagiellon dynasty. From Alibris.

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth The Polish-Lithuanian State, 1386-1795 by Daniel Z. Stone. For four centuries, the Polish-Lithuanian state encompassed present-day Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, Russia, Latvia, Estonia, and Romania. Governed by a constitutional monarchy, it enjoyed unusual domestic tranquility.

The Polish-Lithuanian Monarchy in European Context: C. 1500-1795 edited by Richard Butterwick. Essays assessing the institution and idea of monarchy in one of Europe's largest and most neglected states.

The Other Prussia: Royal Prussia, Poland and Liberty, 1569-1772 deals with the elective monarchy in Poland.

More Books About Lithuania

The first extensive Jewish emigration from Western Europe to Poland occurred at the time of the First Crusade (1098). Under Boleslaw III Krzywousty (1102–1139), the Jews, encouraged by the tolerant régime of this ruler, settled throughout Poland, including over the border into Lithuanian territory as far as Kiev. At the same time Poland saw possible immigration of Khazars, a Turkic tribe that had converted to Judaism. Boleslaw on his part recognized the utility of the Jews it the development of the commercial interests of his country. The Prince of Kraków, Mieszko III the Old (1173–1202), in his endeavor to establish law and order in his domains, prohibited all violence against the Jews, particularly attacks upon them by unruly students (żacy). Boys guilty of such attacks, or their parents, were made to pay fines as heavy as those imposed for sacrilegious acts. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jewish_Polish_history_origins_to_1600s

Disambiguation - Sigismund was the name of several European nobles:

- Saint Sigismund of Burgundy (died 523), King of the Burgundians

- Sigismund of Hungary, Sigismund of Luxembourg (1368–1437), King of Hungary, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Bohemia

- Sigismund Kestutaitis (c.1350–1440), Grand Duke of Lithuania

- Sigismund Korybut (c.1395-c.1435), Lithuanian Duke, participated in Hussite Wars

- Sigismund, Archduke of Austria (1427–1496), ruler of Further Austria

- Archduke Sigismund Francis of Austria (1630-1665), ruler of Further Austria

- Sigismund of Bavaria (1439–1501), a Duke of Bavaria

- Sigismund I the Old (1467–1548), King of Poland, Grand Duke of Lithuania

- Sigismund II Augustus (1520–1572), King of Poland, Grand Duke of Lithuania

- Sigismund III Vasa (1566–1632), King of Sweden (as Sigismund) and Poland, Grand Duke of Lithuania

- Sigismund Báthory (1572–1613), Prince of Transylvania

- Prince Sigismund of Prussia (1864-1866), the fourth child of Friedrich III, German Emperor and Princess Victoria of the United Kingdom

Golden age under Sigismund and Sigusmund II

The most prosperous period in the life of the Polish Jews began with the reign of Sigismund I (1506–1548). In 1507 the king informed the authorities of Lwów

that until further notice its Jewish citizens, in view of losses

sustained by them, were to be left undisturbed in the possession of all

their ancient privileges (Russko-Yevreiski Arkhiv, iii.79). His generous treatment of his physician, Jacob Isaac, whom he made a member of the nobility in 1507, testifies to his liberal views.

But while Sigismund himself was prompted by feelings of justice, his courtiers endeavored to turn to their personal advantage the conflicting interests of the different classes. Sigismund's second wife, Italian born Queen Bona, sold government positions for money; and her favorite, the Voivode (district governor) of Kraków, Piotr Kmita, accepted bribes from both sides, promising to further the interests of each at the Sejm (Polish parliament) and with the king. In 1530 the Jewish question was the subject of heated discussions at the Sejm. There were some delegates who insisted on the just treatment of the Jews. On the other hand, some went so far as to demand the expulsion of the Jews from the country, while still others wished to curtail their commercial rights. The Sejm of 1538 in Piotrków Trybunalski elaborated a series of repressive measures against the Jews, who were prohibited from engaging in the collection of taxes and from leasing estates or government revenues, "it being against God's law that these people should hold honored positions among the Christians." The commercial pursuits of the Jews in the cities were placed under the control of the hostile magistrates, while in the villages Jews were forbidden to trade at all. The Sejm also revived the medieval ecclesiastical law compelling the Jews to wear a distinctive badge.

Sigismund II Augustus (1548–1572) followed in the main the tolerant policy of his father. He confirmed the ancient privileges of the Polish Jews, and considerably widened and strengthened the autonomy of their communities. By a decree of August 13, 1551, the Jews of Great Poland were again granted permission to elect a chief rabbi, who was to act as judge in all matters concerning their religious life. Jews refusing to acknowledge his authority were to be subject to a fine or to excommunication; and those refusing to yield to the latter might be executed after a report of the circumstances had been made to the authorities. The property of the recalcitrants was to be confiscated and turned in to the crown treasury. The chief rabbi was exempted from the authority of the voivode and other officials, while the latter were obliged to assist him in enforcing the law among the Jews.

Blood libel: Legend of the Jew calling the Devil from a Vessel of Blood.--Facsimile of a Woodcut in Boaistuau's "Histoires Prodigieuses:" in 4to, Paris, Annet Briere, 1560.

The favorable attitude of the King and of the enlightened nobility could not prevent the growing animosity against the Jews in certain parts of the kingdom. The Reformation movement stimulated an anti-Jewish crusade by the Catholic clergy, who preached vehemently against all "heretics": Lutherans, Calvinists, and Jews. In 1550 the papal nuncio Alois Lipomano, who had been prominent as a persecutor of the Neo-Christians in Portugal, was delegated to Kraków to strengthen the Catholic spirit among the Polish nobility. He warned the King of the evils resulting from his tolerant attitude toward the various non-believers in the country. Seeing that the Polish nobles, among whom the Reformation had already taken strong root, paid but scant courtesy to his preachings, he initiated a blood libel in the town of Sochaczew. Sigismund pointed out that papal bulls had repeatedly asserted that all such accusations were without any foundation whatsoever; and he decreed that henceforth any Jew accused of having committed a murder for ritual purposes, or of having stolen a host, should be brought before his own court during the sessions of the Sejm. Sigismund II Augustus also granted autonomy to the Jews in the matter of communal administration and laid the foundation for the power of the Kahal.

In 1569 Union of Lublin Lithuania strengthened its ties with Poland, as the previous personal union was peacefully transformed into a unique federation of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The death of Sigismund Augustus (1572) and thus the termination of the Jagiellon dynasty necessitated the election of his successor by the elective body of all the nobility (szlachta). During the interregnum szlachta has passed the Warsaw Confederation act which guaranteed unprecedented religious tolerance to all citizens of the Commonwealth. Meanwhile, the neighboring states were deeply interested in the elections, each hoping to insure the choice of its own candidate. The pope was eager to assure the election of a Catholic, lest the influences of the Reformation should become predominant in Poland. Catherine de' Medici was laboring energetically for the election of her son Henry of Anjou. But in spite of all the intrigues at the various courts, the deciding factor in the election was the influence of Solomon Ashkenazi, then in charge of the foreign affairs of Ottoman Empire. Henry of Anjou was elected, which was of deep concern to the liberal Poles and the Jews, as he was the infamous mastermind of the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre. Therefore Polish szlachta forced him to sign the Henrician articlespacta conventa, guarantying the religious tolerance in Poland, as a condition of acceptance of the throne (those documents would be subsequently signed by every other elected Polish king). However, Henry soon secretly fled to France after a reign in Poland of only a few months, in order to succeed his deceased brother Charles IX on the French throne.

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1572-1795

Main article: History of Poland (1569-1795) Jewish learning and culture during the early Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth Yeshivas were established, under the direction of the rabbis, in the more prominent communities. Such schools were officially known as gymnasia, and their rabbi-principals as rectors. Important yeshivots existed in Kraków, Poznań, and other cities. Jewish printing establishments came into existence in the first quarter of the 16th century. In 1530 a Hebrew Pentateuch (Torah) was printed in Kraków; and at the end of the century the Jewish printing-houses of that city and Lublin issued a large number of Jewish books, mainly of a religious character. The growth of Talmudic Jewish law. Polish Jewry found its views of life shaped by the spirit of Talmudic and rabbinical literature, whose influence was felt in the home, in school, and in the synagogue.

Shalom Shachna (c. 1500–1558), a pupil of Pollak, is counted among the pioneers of Talmudic learning in Poland. He lived and died in Lublin, where he was the head of the yeshivah which produced the rabbinical celebrities of the following century. Shachna's son Israel became rabbi of Lublin on the death of his father, and Shachna's pupil Moses Isserles (known as the ReMA) (1520–1572) achieved an international reputation among the Jews as the co-author of the Shulkhan Arukh, (the "Code of Jewish Law"). His contemporary and correspondent Solomon Luria (1510–1573) of Lublin also enjoyed a wide reputation among his coreligionists; and the authority of both was recognized by the Jews throughout Europe. Among the famous pupils of Isserles should be mentioned David Gans and Mordecai Jaffe, the latter of whom studied also under Luria. Another distinguished rabbinical scholar of that period was Eliezer b. Elijah Ashkenazi (1512–1585) of Kraków. His Ma'ase ha-Shem (Venice, 1583) is permeated with the spirit of the moral philosophy of the Sephardic school, but is extremely mystical. At the end of the work he attempts to forecast the coming of the Jewish Messiah in 1595, basing his calculations on the Book of Daniel. Such Messianic dreams found a receptive soil in the unsettled religious conditions of the time. The new sect of Socinians or Unitarians, which denied the Trinity and which, therefore, stood near to Judaism, had among its leaders Simon Budny, the translator of the Bible into Polish, and the priest Martin Czechowic. Heated religious disputations were common, and Jewish scholars participated in them. At the same time, the Kabbalah had become entrenched under the protection of Rabbinism; and such scholars as Mordecai Jaffe and Yoel Sirkis devoted themselves to its study. The mystic speculations of the kabalists prepared the ground for Sabbatianism, and the Jewish masses were rendered even more receptive by the great disasters that over-took the Jews of Poland during the middle of the 17th century such as the Cossack Chmielnicki Uprising against Poland during 1648–1654.

The beginning of decline - Stephen Báthory (1576–1586) was now elected king of Poland; and he proved both a tolerant ruler and a friend of the Jews. On February 10, 1577, he sent orders to the magistrate of Pozna directing him to prevent class conflicts, and to maintain order in the city. His orders were, however, of no avail. Three months after his manifesto a riot occurred in Poznań. Political and economic events in the course of the 16th century forced the Jews to establish a more compact communal organization, and this separated them from the rest of the urban population; indeed, although with few exceptions they did not live in separate ghettos, they were nevertheless sufficiently isolated from their Christian neighbors to be regarded as strangers. They resided in the towns and cities, but had little to do with municipal administration, their own affairs being managed by the rabbis, the elders, and the dayyanim or religious judges. These conditions contributed to the strengthening of the Kahal organizations. Conflicts and disputes, however, became of frequent occurrence, and led to the convocation of periodical rabbinical congresses, which were the nucleus of the central institution known in Poland, from the middle of the 16th to the middle of the 18th century, as the Council of Four Lands.

Under the rule of Sigismund III Vasa, the privileges of all non-Catholics in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth were limited. The Catholic reaction which with the aid of the Jesuits and the Council of Trent spread throughout Europe finally reached Poland. The Jesuits and counterreformation found a powerful protector in Báthory's successor, Sigismund III Vasa (1587–1632). Under his rule the "Golden Freedom" of the Polish szlachta gradually became perverted; government by the liberum veto undermined the authority of the Sejm; and the stage was set for the degeneration of unique democracy and religious tolerance of the Commonwealth into anarchy and intolerance. However, the dying spirit of the republic (Rzeczpospolita) was still strong enough to check somewhat the destructive power of Jesuitism, which under an absolute monarchy, like those in Western Europe, have led to drastic anti-Jewish measures similar to those that had been taken in Spain. However in Poland Jesuits were limited only to propaganda. Thus while the Catholic clergy was the mainstay of the anti-Jewish forces, the king, forced by the Protestant szlachta, remained at least in semblance the defender of the Jews. Still, the false accusations of ritual murder against the Jews recurred with growing frequency, and assumed an "ominous inquisitional character." The papal bulls and the ancient charters of privilege proved generally of little avail as protection. Uneasy conditions persisted during the reign of Sigismund's son, Wladislaus IV Vasa (1632–1648).

But while Sigismund himself was prompted by feelings of justice, his courtiers endeavored to turn to their personal advantage the conflicting interests of the different classes. Sigismund's second wife, Italian born Queen Bona, sold government positions for money; and her favorite, the Voivode (district governor) of Kraków, Piotr Kmita, accepted bribes from both sides, promising to further the interests of each at the Sejm (Polish parliament) and with the king. In 1530 the Jewish question was the subject of heated discussions at the Sejm. There were some delegates who insisted on the just treatment of the Jews. On the other hand, some went so far as to demand the expulsion of the Jews from the country, while still others wished to curtail their commercial rights. The Sejm of 1538 in Piotrków Trybunalski elaborated a series of repressive measures against the Jews, who were prohibited from engaging in the collection of taxes and from leasing estates or government revenues, "it being against God's law that these people should hold honored positions among the Christians." The commercial pursuits of the Jews in the cities were placed under the control of the hostile magistrates, while in the villages Jews were forbidden to trade at all. The Sejm also revived the medieval ecclesiastical law compelling the Jews to wear a distinctive badge.

Sigismund II Augustus (1548–1572) followed in the main the tolerant policy of his father. He confirmed the ancient privileges of the Polish Jews, and considerably widened and strengthened the autonomy of their communities. By a decree of August 13, 1551, the Jews of Great Poland were again granted permission to elect a chief rabbi, who was to act as judge in all matters concerning their religious life. Jews refusing to acknowledge his authority were to be subject to a fine or to excommunication; and those refusing to yield to the latter might be executed after a report of the circumstances had been made to the authorities. The property of the recalcitrants was to be confiscated and turned in to the crown treasury. The chief rabbi was exempted from the authority of the voivode and other officials, while the latter were obliged to assist him in enforcing the law among the Jews.

Blood libel: Legend of the Jew calling the Devil from a Vessel of Blood.--Facsimile of a Woodcut in Boaistuau's "Histoires Prodigieuses:" in 4to, Paris, Annet Briere, 1560.

The favorable attitude of the King and of the enlightened nobility could not prevent the growing animosity against the Jews in certain parts of the kingdom. The Reformation movement stimulated an anti-Jewish crusade by the Catholic clergy, who preached vehemently against all "heretics": Lutherans, Calvinists, and Jews. In 1550 the papal nuncio Alois Lipomano, who had been prominent as a persecutor of the Neo-Christians in Portugal, was delegated to Kraków to strengthen the Catholic spirit among the Polish nobility. He warned the King of the evils resulting from his tolerant attitude toward the various non-believers in the country. Seeing that the Polish nobles, among whom the Reformation had already taken strong root, paid but scant courtesy to his preachings, he initiated a blood libel in the town of Sochaczew. Sigismund pointed out that papal bulls had repeatedly asserted that all such accusations were without any foundation whatsoever; and he decreed that henceforth any Jew accused of having committed a murder for ritual purposes, or of having stolen a host, should be brought before his own court during the sessions of the Sejm. Sigismund II Augustus also granted autonomy to the Jews in the matter of communal administration and laid the foundation for the power of the Kahal.

In 1569 Union of Lublin Lithuania strengthened its ties with Poland, as the previous personal union was peacefully transformed into a unique federation of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The death of Sigismund Augustus (1572) and thus the termination of the Jagiellon dynasty necessitated the election of his successor by the elective body of all the nobility (szlachta). During the interregnum szlachta has passed the Warsaw Confederation act which guaranteed unprecedented religious tolerance to all citizens of the Commonwealth. Meanwhile, the neighboring states were deeply interested in the elections, each hoping to insure the choice of its own candidate. The pope was eager to assure the election of a Catholic, lest the influences of the Reformation should become predominant in Poland. Catherine de' Medici was laboring energetically for the election of her son Henry of Anjou. But in spite of all the intrigues at the various courts, the deciding factor in the election was the influence of Solomon Ashkenazi, then in charge of the foreign affairs of Ottoman Empire. Henry of Anjou was elected, which was of deep concern to the liberal Poles and the Jews, as he was the infamous mastermind of the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre. Therefore Polish szlachta forced him to sign the Henrician articlespacta conventa, guarantying the religious tolerance in Poland, as a condition of acceptance of the throne (those documents would be subsequently signed by every other elected Polish king). However, Henry soon secretly fled to France after a reign in Poland of only a few months, in order to succeed his deceased brother Charles IX on the French throne.

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1572-1795

Main article: History of Poland (1569-1795) Jewish learning and culture during the early Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth Yeshivas were established, under the direction of the rabbis, in the more prominent communities. Such schools were officially known as gymnasia, and their rabbi-principals as rectors. Important yeshivots existed in Kraków, Poznań, and other cities. Jewish printing establishments came into existence in the first quarter of the 16th century. In 1530 a Hebrew Pentateuch (Torah) was printed in Kraków; and at the end of the century the Jewish printing-houses of that city and Lublin issued a large number of Jewish books, mainly of a religious character. The growth of Talmudic Jewish law. Polish Jewry found its views of life shaped by the spirit of Talmudic and rabbinical literature, whose influence was felt in the home, in school, and in the synagogue.

Shalom Shachna (c. 1500–1558), a pupil of Pollak, is counted among the pioneers of Talmudic learning in Poland. He lived and died in Lublin, where he was the head of the yeshivah which produced the rabbinical celebrities of the following century. Shachna's son Israel became rabbi of Lublin on the death of his father, and Shachna's pupil Moses Isserles (known as the ReMA) (1520–1572) achieved an international reputation among the Jews as the co-author of the Shulkhan Arukh, (the "Code of Jewish Law"). His contemporary and correspondent Solomon Luria (1510–1573) of Lublin also enjoyed a wide reputation among his coreligionists; and the authority of both was recognized by the Jews throughout Europe. Among the famous pupils of Isserles should be mentioned David Gans and Mordecai Jaffe, the latter of whom studied also under Luria. Another distinguished rabbinical scholar of that period was Eliezer b. Elijah Ashkenazi (1512–1585) of Kraków. His Ma'ase ha-Shem (Venice, 1583) is permeated with the spirit of the moral philosophy of the Sephardic school, but is extremely mystical. At the end of the work he attempts to forecast the coming of the Jewish Messiah in 1595, basing his calculations on the Book of Daniel. Such Messianic dreams found a receptive soil in the unsettled religious conditions of the time. The new sect of Socinians or Unitarians, which denied the Trinity and which, therefore, stood near to Judaism, had among its leaders Simon Budny, the translator of the Bible into Polish, and the priest Martin Czechowic. Heated religious disputations were common, and Jewish scholars participated in them. At the same time, the Kabbalah had become entrenched under the protection of Rabbinism; and such scholars as Mordecai Jaffe and Yoel Sirkis devoted themselves to its study. The mystic speculations of the kabalists prepared the ground for Sabbatianism, and the Jewish masses were rendered even more receptive by the great disasters that over-took the Jews of Poland during the middle of the 17th century such as the Cossack Chmielnicki Uprising against Poland during 1648–1654.

The beginning of decline - Stephen Báthory (1576–1586) was now elected king of Poland; and he proved both a tolerant ruler and a friend of the Jews. On February 10, 1577, he sent orders to the magistrate of Pozna directing him to prevent class conflicts, and to maintain order in the city. His orders were, however, of no avail. Three months after his manifesto a riot occurred in Poznań. Political and economic events in the course of the 16th century forced the Jews to establish a more compact communal organization, and this separated them from the rest of the urban population; indeed, although with few exceptions they did not live in separate ghettos, they were nevertheless sufficiently isolated from their Christian neighbors to be regarded as strangers. They resided in the towns and cities, but had little to do with municipal administration, their own affairs being managed by the rabbis, the elders, and the dayyanim or religious judges. These conditions contributed to the strengthening of the Kahal organizations. Conflicts and disputes, however, became of frequent occurrence, and led to the convocation of periodical rabbinical congresses, which were the nucleus of the central institution known in Poland, from the middle of the 16th to the middle of the 18th century, as the Council of Four Lands.

Under the rule of Sigismund III Vasa, the privileges of all non-Catholics in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth were limited. The Catholic reaction which with the aid of the Jesuits and the Council of Trent spread throughout Europe finally reached Poland. The Jesuits and counterreformation found a powerful protector in Báthory's successor, Sigismund III Vasa (1587–1632). Under his rule the "Golden Freedom" of the Polish szlachta gradually became perverted; government by the liberum veto undermined the authority of the Sejm; and the stage was set for the degeneration of unique democracy and religious tolerance of the Commonwealth into anarchy and intolerance. However, the dying spirit of the republic (Rzeczpospolita) was still strong enough to check somewhat the destructive power of Jesuitism, which under an absolute monarchy, like those in Western Europe, have led to drastic anti-Jewish measures similar to those that had been taken in Spain. However in Poland Jesuits were limited only to propaganda. Thus while the Catholic clergy was the mainstay of the anti-Jewish forces, the king, forced by the Protestant szlachta, remained at least in semblance the defender of the Jews. Still, the false accusations of ritual murder against the Jews recurred with growing frequency, and assumed an "ominous inquisitional character." The papal bulls and the ancient charters of privilege proved generally of little avail as protection. Uneasy conditions persisted during the reign of Sigismund's son, Wladislaus IV Vasa (1632–1648).

Peak of the Empire

The Polish Nobility by Margaret Odrowaz-Sypniewska

The Polish Nobility emerged as a clan (family or tribe) system before 1000 A.D. Each clan had its own mark, a tamga, which eventually evolved into the symbols found on Polish coats of arms. The noble class became landowners. Most noble surnames were taken from the names of estates, called "family nests." For example, Sypniewski was named because they have estates called Sypniewo.

Sometimes the Polish "z" was used at the end of a name to mean "of" or "from." During the fifteeenth century the "z" was changed to "ski" or "cki," which also meant "of" or "from." For example: Jan Debinski or Jan Debricki. Originally, people who were not nobles were forbidden to add "ski" or "cki" to their surname.

While it is true that having surnames ending in "ski" or "cki" originally meant the bearer was of noble birth, but eventually many peasants, living on their lord's land, took their employer's surnames. These people were NOT related to him or of noble birth. The closest thing to this is slaves and servants taking the names of their masters.

Most noblemen in Poland and Lithuania claimed only to belong to the szlachta odwieczna or immemorial nobility. This meant that all knowledge of their origins had long since been lost, and was beyond their memory. Szlachta combined "high birth" and "military prowess" together in medieval times. Nobles were originally tribal chiefs.

There was a great difference between the land barons of England and the magnates of Poland. The power of the English or French lord, at this time, was held from the crown and fitted into a whole system of vassalage, with feudal tenants who held land in fief (an estate) from a lord to whom he owned allegiance. Polish society had evolved from clannish structures, and the introduction of Christianity (and all that went with it), did not alter these significantly. The feudal system which regulated society all over Europe was never introduced in Poland, and this fact can not be stressed too heavily.

Poland had a large nobility. About ten percent (10%) of the population was noble, as compared to the one (1%) to two (2%) percent in the rest of Europe. The Polish State was set up to serve the Polish nobleman.

The szlachta (nobility) inherited both status and land. They were, however, obligated to perform military service for the king, and to submit to his tribunals (his court of moral principles or laws), but they were the independant magistrates over their own lands. In the rest of Europe, the nobles did everything possible to avoid military service. The Polish nobles and military dressed very flamboyantly.

In 1550, nobility was allowed to purchase a house in cities, and to enjoy them without paying municipal taxes, notwithstanding all local legislation to the contrary. From 1573, the nobles had exclusive rights to use the timber and minerals on their land.

Polish nobles first divided everything equally to their sons and unmarried daughters alike. This resulted in loss of wealth in later generations, so that the system changed to eldest male (who had to serve in the military). Nobles felt exclusive and they were biologically unique. There was no strong feelings about bastardy, intermarriage, or miscegenation - only that the children of the irregular unions could not claim nobility.

The Polish nobles had a proverb: "Nightingales are not born from owls." Nobles were pure. A nobleman was worth more than a peasant (in their eyes). Therefore, the murder of a noble brought 58 weeks in a closed dungeon and a fine of 240 groats. If a firearm was used, the sentence was extended to 115 weeks in jail and 480 groats. Legs, arms, eyes, and noses of nobles were priced at 120 groats each; blood wounds at 80 groats, fingers at 30 groats, and teeth at 20 groats. No mention was made of peasant victims. Presumably these cases of wrong doing were not taken to court?

Noblemen always carried a sword to defend themselves. In 1448, the death sentence was established for the rape of a noblewoman by a commoner. A commoner, who was raped, was given 60 groats. This meant that a raped noblewoman was worth two dead noblemen, and the hymen of a peasant girl was much more valuable than the life of her father. Nobles were labelled" "proud," "obstinate," "passionate," and "furious." http://www.angelfire.com/mi4/polcrt/PolNobility.html

DESCENDANTS of the Great Sejm - http://www.sejm-wielki.pl/en.php

The szlachta (Polish: szlachta, [ˈʂlaxta]( listen), Lithuanian: šlėkta, šlėktos or bajorai ) was a privileged class with origins in the Kingdom of Poland. It gained considerable institutional privileges during the 1333-1370 reign of Casimir the Great.[1] In 1413, following a series of tentative personal unions between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland, the existing Lithuanian nobility formally joined the class.[1] As the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1795) evolved, its membership grew to include leaders of Ducal Prussia and the Ruthenian lands.

The origins of the szlachta are unclear and have been the subject of a variety of theories.[1] Traditionally, its members were owners of landed property, often in the form of folwarks. The nobility negotiated substantial and increasing political privileges for itself until the late 18th century.

During the Partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth from 1772 to 1795, its members lost their privileges. Until 1918, the legal status of the nobility was then dependent on policies of the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Habsburg Monarchy. Its privileges were legally abolished in the Second Polish Republic by the March Constitution in 1921.

The Polish term "szlachta" designates the formalized, hereditary noble class. In official Latin documents, the old Commonwealth hereditary szlachta is referred to as "nobilitas" and is equivalent to English nobility. A widespread misconception resulted from translating "szlachta" as "gentry" because some nobles were poor (SEE: Estates of the Realm regarding wealth and nobility). Some were even poorer than non-noble gentry, the non-noble gentry declining with the 'second serfdom' and re-emerging after the Partitions. Some nobles even became tenants of wealthier gentry, while still retaining their constitutional superiority. It was not wealth or lifestyle (obtainable by the gentry) that constituted nobility, but hereditary, juridical status. A specific nobleman was called a "szlachcic," and a noblewoman, a "szlachcianka."

"Szlachta" derives from the Old German word "slahta" (now "(Adels) Geschlecht", "(noble) family"), much as many other Polish words pertaining to the nobility derive from German words — e.g., the Polish "rycerz" ("knight", cognate of the German "Ritter") and the Polish "herb" ("coat of arms", from the German "Erbe", "heritage"). Poles of the 17th century assumed that "szlachta" was from the German "schlachten" ("to slaughter" or "to butcher"); also suggestive is the German "Schlacht" ("battle"). Early Polish historians thought the term may have derived from the name of the legendary proto-Polish chief, Lech, mentioned in Polish and Czech writings.

Kindred terms that might be applied to an early Polish nobleman were "rycerz" (from German Ritter, "knight"), the Latin "nobilis" ("noble"; plural: "nobiles") and "możny" ("magnate", "oligarch"; plural: "możni"). Some powerful Polish nobles were referred to as "magnates" (Polish singular: "magnat", plural: "magnaci"). It has to be remembered however, that not all knights were nobles.

Today the word szlachta in the Polish language denotes any noble class in the world. In broadest meaning, it can also denote some non-hereditary honorary knighthoods granted today by some European monarchs. Even some 19th century non-noble land owners would be called szlachta by courtesy or error as they owned manorial estates but were not noble by birth. In the narrow sense it denotes the old-Commonwealth nobility.

The origins of the szlachta have always been unclear.[1] As a result, its members often referred to it as odwieczna (perennial).[1] Two popular historic theories of origin forwarded by its members and earlier historians and chroniclers involved descent from the Sarmatians or from Japheth, one of Noah's sons (by contrast, the peasantry were said to be the offspring of another son of Noah, Ham - and hence subject to bondage under the Curse of Ham[2] - and the Jews as the offspring of Shem).[1][3]

Other, since discredited theories included its foundation by Julius Caesar, Alexander the Great, alien visitations, and regional leaders who had not mixed their bloodlines with those of 'slaves, prisoners, and aliens'.[1] Another theory describes its derivation from a Slavic warrior class, forming a distinct element within the ancient Polonic tribal groupings (SEE: Indo-European caste systems). Around the 14th century, there was little difference between knights and the szlachta in Poland, apart from legal and economic. Members of the szlachta had the personal obligation to defend the country (pospolite ruszenie), thereby becoming the kingdom's privileged social class. Inclusion in the class was usually based on inheritance.[4]

Concerning the early Polish tribes, geography contributed to long-standing traditions. The Polish tribes were internalized and organized around a unifying religious cult, governed by the wiec, an assembly of free tribesmen. Later, when safety required power to be consolidated, an elected prince was chosen to govern.

The tribes were ruled by clans (ród) consisting of people related by blood and descending from a common ancestor, giving the ród/clan a highly developed sense of solidarity. (See gens.) The starosta (or starszyna) had judicial and military power over the ród/clan, although this power was often exercised with an assembly of elders. Strongholds called grόd were built where the religious cult was powerful, where trials were conducted, and where clans gathered in the face of danger. The opole was the territory occupied by a single tribe. (Manteuffel 1982, p. 44).

Mieszko I of Poland (c. 935 – 25 May 992) utilized an elite knightly retinue from his army, which he depended upon for success in uniting the Lekhitic tribes and preserving the unity of his state. Documented proof exists of Mieszko I's successors utilizing such a retinue, too.

Stanisław Antoni Szczuka, a Polish nobleman Another class of knights were granted land by the prince, allowing them to serve the prince militarily. A Polish nobleman living at this time before the 15th century was referred to as a "rycerz", very roughly equivalent to the English "knight," the critical difference being the status of "rycerz" was strictly hereditary; the class of all such individuals was known as the "rycerstwo". Representing the wealthier families of Poland and itinerant knights from abroad seeking their fortunes, this other class of rycerstwo, which became the szlachta/nobility ("szlachta" becomes the proper term for Polish nobility beginning about the 15th century), gradually formed apart from Mieszko I's and his successors' elite retinues. This rycerstwo/nobility obtained more privileges granting them favored status. They were absolved from particular burdens and obligations under ducal law, resulting in the belief only rycerstwo (those combining military prowess with high/noble birth) could serve as officials in state administration.

Select rycerstwo were distinguished above the other rycerstwo, because they descended from past tribal dynasties, or because early Piasts' endowments made them select beneficiaries. These rycerstwo of great wealth were called możni (Magnates). Socially they were not a distinct class from the rycerstwo they originated from and to which they would return were their wealth lost. (Manteuffel 1982, pp. 148–149).